Tigray Genocide

“They were knocking door to door. To rape the women and kill the men. They took my cousin Hadush, who was 24 years old together with 72 other young men. They took them to the mountains and killed them all.” – Goitom, on the Mahbere Dego Massacre. In a time where polarization thrives and where we all identify in boxes and ranks common points are harder to find. What do a humanitarian aid worker, two students and a legal agent have in common? All have been tangled up in a long journey in their mother land. They were forced to flee to a new country on a new continent where they don’t speak the language far from their families and friends. They’ve faced prison, torture, shootings, and bombings. All for speaking a certain language, for looking a certain way, for having certain names, for carrying a certain identity. The identity of a Tigrayan in Ethiopia. Abiy Ahmed, Prime Minister of Ethiopia and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize 2019 succeeded in his hunt for Tigrayan civilians and together with his allies managed to kill at least 600.000 Tigrayan civilians in two years’ time.

I meet Gebrekirstos Gebreselassie for a coffee in Amsterdam, The Netherlands on a Friday morning in March 2023. Gebrekirstos is Tigrayan and the founder and chief editor of Tghat. The platform Tghat documents the destruction that has been taking place in Tigray, the Northern part of Ethiopia, since November 2020. The platform was created as a response to the lockdown of the region, including all media and telecommunications by the Ethiopian government since the beginning of the war. Gebrekirstos: “I truly don’t understand why there is so little attention for this conflict in the media and so little interests by educational organizations such as The Africa Institute in Leiden. The only reporting from the Netherlands that I see is with so-called experts who had ‘once’ been to Ethiopia, but no accounts from Tigrayans themselves. This is completely incomprehensible to me. There are so many Tigrayan people who can and want to tell their story. There have been many Tigrayan refugees arriving the past month in the Netherlands. People who lived the war, who have seen it with their own eyes and can tell their story.”

With this message in mind, I contacted four refugees from Tigray in the Netherlands who are open to share their story with me. I first spoke with Goitom, 23 years old in a public library in the Netherlands. Goitom loves studying and finished his bachelor’s degree in engineering in Addis Ababa during the war. Seldom I’ve seen someone’s eyes light up like Goitom’s when talking about university. His siblings also studied in university and now Goitom wants to follow their path and become an engineer. However, he does not know if his siblings or his parents are alive. He has not heard from them since the war.

A few days later I meet with Atsbha, 38 years old at the emergency refugee camp, which is located in a hotel nearby Schiphol Airport. Upon arrival Atsbha welcomes me at the entrance. The hotel looks busy and chaotic. When we walk down the hall, there is a renovation on the left and on the right, it is filled with corporate people in suit drinking their lattes and discussing business deals. It is hard to find a place where we can sit down and where Atsbha feels comfortable to tell his story. I don’t see any other refugees which seems strange to me, I guess they’re somewhere on the other side of the hotel, at least not close to the corporates at the entrance. Atsbha tells me he has been staying in this hotel for the past eleven months. His wife and children are in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. He fled the country almost a year ago and is still waiting for information from the Dutch Immigration Office. In his home country he was an active humanitarian aid worker, leading all humanitarian response programs at an international humanitarian aid organization. Atsbha: “I was helping internally displaced people and refugees from poverty and hunger. It is strange to be on the other side. Now that I’m the one depending on the Dutch government for receiving my meals, and the roof over my head.”

The next week I meet with Robel, 24 years old in the public library of Amsterdam. Robel is waiting for me in front of the water, he arrived by bike from the refugee center. When we greet each other, he gives me a big smile and tells me he is quite amazed by the enormous library. Robel graduated in software engineering in Addis Ababa and has been living in the Netherlands for the past nine months. He has two sisters of 28 and 18 years old. He recently learned they are alive in Ethiopia but hasn’t heard from his parents since he fled the war.

One week later I take the train to meet Selam in a public a library in Wageningen. Selam is 29 years old and has been working as an assistant transmitter and legal distributing agent for a shoes factory in Addis Ababa. She appears shy at the beginning of our conversation, guarded. Selam has a brother and sister of 31 and 21 years old. From the last information she has they are in Mekelle the capital of Tigray and her dad must be somewhere in Ethiopia. Her brother has a degree in journalism and fled with her sister to Mekelle during the war. Selam’s sister was supposed to go to university but had to stay in High School since educational facilities were destroyed. Selam doesn’t know if her siblings are safe, or even alive. She hasn’t been able speak to them since July 2021. Selam’s mom is in a refugee camp in Sudan. She is a nurse and was in Sudan for work when the war broke out and had to seek refuge in the country. Selam is extremely worried about the safety of her mom, especially since civil war broke out in Sudan: “She is all by herself, I don’t know if she is safe, I can’t talk to her because the network is extremely bad.”

Historical context

Ethiopia is one of the oldest countries in Africa and the only country in the continent that has not been colonized. Ethiopia distinguishes more than 90 different ethnic groups with their own distinct language spread out over the country. Its population counts more than 126 million people. The biggest minorities are the Oromo who make up for about 43 million people, with its capital Addis Ababa, in the southwest of Ethiopia. The second minority is the Amhara population who make up for around 34.4 million people, in the northwest of Ethiopia. The third minority are the Somali with around 7.8 million people in eastern Ethiopia. The fourth biggest minority are the Tigrayan who’s population make up for 7.6 million people, with its capital Mekelle, in the north of Ethiopia.

Richard Reid, Professor of African History seeks to place the recent war in a deeper historical context. Ethiopia has never been colonized contrary to its neighboring country Eritrea that became an Italian colony under fascist rule from 1890 till 1941. On the map of Ethiopia, you can see that the Tigray region borders Eritrea. The territory of the Tigrayans however did not limit its borders to Ethiopia. Tigrayans have been living in Eritrea as well. The colonization of Eritrea left a complex and ambiguous relation between Tigrayans on both sides of the borders. While Eritrea was colonized by the Italians, Ethiopia was living under the Monarchy of Emperor Haile Selassie who annexed Eritrea in 1962. Haile Selassie was eventually ousted in both countries in 1974. This resulted in both countries being ruled under the military rule of the Marxist and authoritarian Derg regime, supported by the Soviet Union.

High ranking Derg members: Mengistu Haile Mariam, Tafari Benti and Atnafu Abate. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Insurgency movements were formed to overthrow the Derg regime. The main players in the insurgency movements were the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). The TPLF was partly a product of student radicalism due to decades of marginalization and impoverishment of the Tigray people in imperial Ethiopia. Its fighters got trained with help from the EPLF. Together they succeeded in overthrowing the Derg regime. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front installed a new government in Ethiopia and Eritrea gained its independence in 1993. However, the EPLF did not only seek independence but also wanted its share of political and military power in Ethiopia since they contributed to the creation of the TPLF. This did not end well and in 1998 the TPLF went to war with Eritrea. To gain power the TPLF fought and destroyed rival rebel groups and when they installed its government corruption thrived. The TPLF’s former leader Meles Zenawi made sure Tigrayans dominated in the army and intelligence services, and consolidated jobs for former comrades. Under the rule of the TPLF Ethiopia became an ethnic-based federal state and underwent rapid economic progress. Mekelle, the capital of Tigray flourished, but there was also a growing discontent over the repression imposed by the TPLF.

“As you know TPLF was ruling the country for 27 years and I can say their government is to command and you obey. It’s completely impossible to argue or disobey.” – Robel

“To me the TPLF is like a dictatorship. You need to follow their rules and they only care about their power.” – Goitom

Abiy Ahmed

Abiy Ahmed Ali came to power as the Prime Minister of Ethiopia in 2018, replacing the repressive government of the TPLF. Abiy Ahmed is of mixed Oromo and Amhara decedent. He was part of one of the insurgency movements against the Derg regime, fighting alongside the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF). Later he rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the ENDF and occupied several positions within the Ethiopian government. Abiy Ahmed started his career as Prime Minister in a country that was in deep political crisis. At the start of his career, he made drastic political reforms. He released thousands of political prisoners, appointed a gender-balanced cabinet, eased up restrictions on civil liberties and made a peace deal with Eritrea, which is known to have a powerful army and one of the world’s most repressive governments. The latter made him win the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019. In their press announcement the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced to award the Nobel Peace Prize to Abiy Ahmed Ali: ‘for his efforts to achieve peace and international corporation, and in particular for his decisive initiative to resolve the border conflict with neighboring Eritrea’.

Abiy Ahmed receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019

Abiy Ahmed did not only manage to solve the border conflict, but also to work together with the Eritrean Defense Force and Amhara militias in their shared grievances against the TPLF and the people of Tigray. This collaboration turned into a nightmare for the more than 7 million Tigrayan civilians living in Ethiopia.

Discrimination

Atsbha: “I have been working as a humanitarian aid worker for the past 12 years in Ethiopia. Before the conflict started in 2020, I was leading the humanitarian response program in the Gambela region, Western Ethiopia. This was the first moment I experienced racial comments from both the local community and government authorities. People were asking my employees if they were still led by ‘the Tigrayan’. Hatred against Tigrayans started and got fueled by speeches in the media of federal government officials like Daniel Kibret. They are making the division between the people of Tigray and the rest of Ethiopia and started to call us Juntas, which means terrorist or soldier that disobeys the government. I got asked to leave the region several times and received threatening calls from police officers. Throughout Ethiopia Tigrayans got fired or bullied away from their jobs and retreated to the Tigray region. When the war started the majority of Tigrayans who were left behind got arrested.”

On the 19th of October 2022, Alice Wairimu Nderitu, UN Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide released a statement in which she addresses and condemns ethnic based hate speech used by political leaders that fuel the conflict: “There is discourse often propagated through social media, which dehumanizes groups by likening them to a ‘virus’ that should be eradicated, to a ‘cancer’ that should be treated because ‘if a single cell is left untreated, that single cell will expand and affect the whole body’ and calling for the ‘killing of every single youth from Tigray’ which is particularly dangerous. Diaspora blogs that call for the genocide of the Tigray people are also of deep concern. Hate speech and incitement to violence are fueling the normalization of extreme violence not just in Tigray and neighboring Amhara and Afar regions, but in Oromia and other parts of the country too.”

Selam: “I have been working in Addis Ababa before the war started. Discrimination towards Tigrayans is nothing new and was already fiercely present. As an employee of the shoes factory, I had to go to the production floor to check if everything was in order. Whenever I went down there, I felt vulnerable because they are carrying tools which they can easily use if they would want to harm you. If you speak Tigrinya in public, they called you Weyane, now they call you Junta.”

Start of the War

Two years after the start of his career as Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed asked the TPLF to hand over wanted fugitives and join the new political party that he set up to replace the previous ruling coalition, but the TPLF declined. They went ahead with their own regional elections in Tigray in September 2020, while the national elections were officially postponed due to the pandemic. After the illegal regional election Abiy Ahmed accused the TPLF of raiding units on the federal military bases in Tigray, at which many national army officers were killed. Abiy Ahmed followed up on this accusation in the early hours of November 4th 2020 by announcing he had ordered the Ethiopian National Defence Forces to launch a military operation in the Tigray region. Additionally, to the ENDF Eritrean soldiers flooded Tigray from the North and Amhara Special Forces from the South.

Selam in Mekelle

Selam: “I remember going back home for the holidays in September 2020. My family was living in Mekelle. I lived and worked back and forth in Addis Ababa and Mekelle, after becoming a legal distributing agent. It was the night of 3 to 4th of November 2020, when we heard loud noises outside. We first didn’t realize what it was, but when we heard more and more loud bangs nearby the house, we realized the noises were gunshots. The next morning, we discovered two of our neighbors had been shot dead in front of their house.”

Robel in Wukro

Robel: “I was living in Addis Ababa where I graduated my bachelor’s degree in software engineering at the university. During the pandemic I moved back to my family’s home in Wukro, the northeast of Tigray. I remember taking care of my mom in the hospital on the 3rd of November 2020. It was at that moment I heard gunfire for the first time. At first, I thought they were hunting for criminals or undertaking a training exercise. But when the firing continued, and the network went down I suspected something was really off. The next day we heard an army jet coming from Mekelle. They dropped a bomb at the border. The war had started. It didn’t take long for the war to get closer. On the news we started hearing stories of massacres and bombings. Less than a month later my hometown was completely under attack. It was around 4 p.m. in the afternoon when I was with friends on the field where we used to play soccer. One of my best friends was there, his name is Kibrom. He had the most beautiful voice when he sang it was wonderful. We were out on the field, and he was standing ten meters in front of me when it happened. Bombs fell and he got hit right in front of my eyes. He died immediately. The bombardments kept going continuously after that.”

The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHVR) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCR) investigated the war crimes committed in Tigray Ethiopia in a joint investigation. In their report they state that between the 25th and 27th of November 2020 an undisclosed number of civilians died in Wukro.

Goitom in Mahbere Dego

Goitom: “I was studying at the University of Addis Ababa to become an engineer. But during the pandemic I went to Mahbere Dego. When I arrived, the war had started. The TPLF was recruiting young men to fight and taking men from their homes to fight the Eritrean and Amhara soldiers who had killed many civilians from the town.”

On November 9th, 2020, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed posted the following on his Facebook Page: ‘#Ethiopia is grateful for friends expressing their concern. Our rule of law operation is aimed at guaranteeing peace and stability once and for all by bringing perpetrators of instability to justice. Concerns that Ethiopia will descend into chaos are unfounded & a result of not understanding our context deeply. Our rule of law enforcement operation, as a sovereign state with the capacity to manage its own internal affairs, will wrap up soon by ending the prevailing impunity.’

Atsbha in Addis Ababa

Atsbha: “I was born in Nebelet, Tigray but I was working and living in Addis Ababa as a humanitarian aid worker with my family. For my work I was involved in helping internally displaced people and refugees within Ethiopia who were suffering from conflict, drought, and natural disasters. When the conflict started, we immediately changed our attention to Tigray.”

The United Nations Human Rights Council published a report on 31st May 2021 stating that all communications in Tigray were disabled once the conflict began. Access to electricity, water and banking services were suspended and homes, hospitals, churches, mosques, educational institutions, and other civilian structures were bombed.

On the run

Selam: Mekelle to Abiy Addi

Selam: “When we woke up on the 4th of November, we understood the Ethiopian National Defence Force captured the center of Mekelle. With my family we decided to lock ourselves inside the house, where we stayed for 15 days. My mom was alone in Sudan for a work trip, she is a nurse, and is stuck in a refugee camp in Sudan since the war in Tigray started. While we were hiding inside our house the bombing started in Mekelle. My dad called his friends and together with their families we tried to escape to safety. Cars were assembled and with the left-over fuel we tried to make it to Samre. Halfway we ran out of fuel left the cars behind and continued our flee by foot. We hid in a church halfway; it was cold, and we had no blankets. The men separated and went out to search food for the others. After they returned, we tried to get some sleep but heard gunshots again at night. Instead of going to Samre we decided to change direction and move up to the North to a small town called Abiy Addi. In Abiy Addi there was heavy artillery attacks going on as well. After 6 days of fleeing with little food and water we had no choice but to return back to Mekelle. The ENDF had now captured the whole city. They were taking the men, tortured them, threw them in prison or executed them. The women were raped. Even those hiding in the campus of the Medical University in Mekelle. The fear of my sister or myself being raped was immense. Growing up I always felt safe. But now it was totally different. I hid in the house for four months. I only went outside when I really had to and was covering my skin from head to toe only walking in the shadows of the town.”

Mekelle was heavily bombarded through November 2020. In the report of EHCR and OHCR there is written how 29 civilians were killed due to shelling by the ENDF on November 28th. And 87 schools in and around Mekelle were completely destroyed when the ENDF took control of the city. The report also reads how various acts of sexual and gender-based violence including physical violence and assault, rape, gang rape, oral and anal rape, insertion of foreign objects into the vagina and intentional transmission of HIV have been committed by all parties of the conflict. The UN reports that there were more than 2000 allegations of sexual violence against women and girls in the Tigray region during the conflict.

“At one point NGO flights were back up. The federal government stated in the media that everything was under control and people were receiving aid. But this was a complete lie. There was no aid at all. I’ve seen Eritrean forces looting and stealing all the aid from the trucks and storages with my own eyes. In May 2021 I decided to return to Addis Ababa and see if I could get back to work. It was the second phase of the war and ethnic profiling had started in Addis Ababa as well. One day I was at the restaurant and got asked for my ID card for speaking Tigrinya. They arrested me and took me to prison.”

The UN Security Council published a document on 26th August 2021 in which they report that the UN and its humanitarian partners have mobilized to reach more than 5 million people who are in need of humanitarian aid in Tigray. 100 trucks of humanitarian aid were to be expected to reach Mekelle every day. However, since mid-July 2021 only 10 trucks per day made it through, and no trucks have arrived for over a week in the last week of August, due to roadblocks, checkpoints and even the arrests and killings of humanitarian aid workers. All food warehouses are empty.

Atsbha: From Addis Ababa to Nebelet

Atsbha: “I was in Addis Ababa during the war, but I still wanted to help the people in Tigray. At the beginning of the war, I flew down to Tigray many times, to check on the people. But I had to stop because the work became too dangerous for being a Tigrayan myself. When the network went down the humanitarian team in Tigray mostly communicated with us by satellite phone. The only flights that were available were from the UNHAS, the World Food Program (WFP), and humanitarian logistic services. They would try to send money and food via planes, however these deliveries were stopped or got delayed by 6 months. Eritrean soldiers looted almost all humanitarian supplies upon arrival or at roadblocks. Amhara special forces, Eritrean and Fano militias were killing women and elders in their homes, executing youngsters, and looting all public services in Tigray. The region used to be doing well. It was small, but people were living from agriculture and small shops. Now the militias took everything, they stole the cattle’s, destroyed the houses, and burned the crops and the soil. Nothing is left. My friends who work in humanitarian response action were still able to operate in some parts of Tigray. They’ve sent me a picture of Nebelet, the town where my family is from. They were making a needs assessment for the people of Nebelet.”

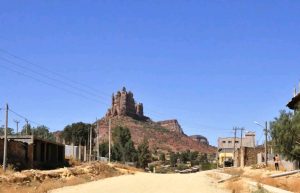

Nebelet, source: Atsbha

“The town had been occupied by Eritrean soldiers and Ethiopian Defense Forces. On the week the picture was taken more than 70 civilians were brutally killed, of which my cousin was one. The town was nearly empty at the time the photo was taken and still now. Most of the residents had escaped the mass killings. The harvest, schools, health centers, water facilities, homes, and shops were looted and destroyed. The people of Nebelet are now totally dependent of humanitarian aid and facing food insecurity due to roadblocks of humanitarian supplies.”

Atsbha: “Speaking Tigrinya in public has never been possible but during the war it was worse. One day I was walking in the street with my youngest son in Addis Ababa who was six at that time. He was speaking Tigrinya because he forgot… well because he is a kid. People in the street started yelling at us calling us Juntas: ‘Hey Juntas what are you still doing in Ethiopia?’. My son asked me: ‘Papa why do they say that? Why are they asking us why we live with them?’ There has been a mass neglection of Tigrayan people all over Ethiopia since the war started. Tigrayans all over the country lost their jobs and got reported on special lists on which employers would point out to security who the Tigrayans are. This happened at all government offices, specifically at Ethiopian airlines, Ethiopian commodity exchange, the Ethiopian National Bank, and all the Ethiopian commercial banks. People got arrested and fired for no reasons, while in prison they got no salary and no way to feed their families. Life in Ethiopia as a humanitarian aid worker being from Tigray became too dangerous for me. Even though I was neutral and focusing on the humanitarian activities all government officials and the neighborhood community suspected me as if I am working for the TPLF. I was followed by Ethiopian police forces to my home and they would knock my door many times to arrest me. Finally, unknown policemen took me from my home and arrested me at midnight.”

Robel: From Wukro to Addis Ababa

Robel: “My best friend Kibrom had just died in front of my eyes due to a bomb that immediately killed him. The bombs continued falling afterwards. Together with my other friends we fled into the mountains, hiding from the bombardments and heavy artillery attacks. We were hiding with a group of ten people when another bomb hit five of my other friends. Three died and one was hit. His face was completely destroyed. The only reason I survived these attacks is the soil we were standing on that muted the impact of the bombs falling down. From the mountains we could see the whole city turning black, one bomb after another had fallen into our city. The noise it makes is immense. When I arrived home my dad ordered me to take my mother and my sisters of 28 and 18 years old and bring them into safety to Atsbi, another town, which is around 6 hours walking from Wukro. My mom was still very sick, and the mountains are very steep. At the foot of the mountain, we found thousands of other people from the town who also decided to flee and helped carrying my mom and sisters to the other side of the mountain. We hid there for two days until we ran out of bread and water. I ate nothing these days and gave all we had to my mother and sisters.”

Hiding in the mountains, source: Robel

“After the two days of hiding, we continued our walk to Atsbi. We started walking from 5 am in the morning and arrived at night. Once we arrived in town, I told my mother and sisters to hide in a safe place so I could search for food. I went door to door begging people from the town for food. That was the moment when Eritrean forces came in unexpectedly. Everybody started running trying to safe their life’s, I had to run as well and lost my family. In the hours that followed I yelled their names and was under complete panic and madness. After hours of yelling and asking people, an old men told me he had seen them. After 6 hours I finally found them back hidden in the dark. My sister had fainted, and my other sister was crying continuously from hunger and fear. We hid there for seven days. People from the town were bringing us a small bread for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. After seven days my mom and sisters asked me to bring them home, back to Wukro: ‘Please bring us home, so we can starve in peace.’”

There have been no official publication showing Atsbi has been attacked by military forces at that time. However several tweets from different twitter users confirm Robel’s account from what happened in Atsbi that day. From December 1st, 2020, till January 30th, 2021, twitter users wrote how Eritrean soldiers had raped, killed, looted, and burned the people and buildings of Atsbi, Tigray.

“I decided to bring my family home. When we arrived, the town was very quiet. There was no one left. We had a beautiful home before the war, now they destroyed and looted everything. But my mother thanked God to be home. My cousin and my dad came back to the town as well. My dad had been hiding in another town and came back as a changed man. I don’t know what he has been through. He used the be a calm man but when he returned, he was yelling and violent towards my sisters and mom. My cousin stayed with us as well after fleeing her town. She thought to be safe with us but one day she was alone with my mother when Eritrean militia broke into the house. They’ve seen my mother sick and raped my cousin. They were raping all women and killing the men. When I arrived home my mom told me to leave: ‘they will kill you.’ I promised her I would find a way out.”

The United Nations Human Rights Council stated in their a report on 31st May 2021 that the involvement of thousands of Eritrean troops in the war is no longer disputed: ‘These soldiers are reportedly involved in extensive looting and destruction of property, including cultural heritage sites, in what some observers describe as cultural cleansing. Churches are reportedly attacked on feast days to ensure casualties are on sites. Close to 200 priests are thought to be among the estimated 50,000 civilian fatalities, including 78 who were killed in one zone, and nuns were raped in their convent in Wukro town.’

“I called my friends who live in Addis Ababa. They bought me a flight ticket since flights were back up. I had no passport, so I had to take the plane with my student ID-card. In Addis Ababa I lived at the university campus where I finished my bachelor’s degree. I had a few other Tigrayan friends at the campus and we met other Tigrayans who bought as a beautiful suit for our graduation day because they felt bad for what happened to us. After graduation we were ordered to leave the campus. We told the university that there is war at our homes and had no place to go. But the university staff did not care because we were ‘Juntas’. After begging Tigrayan families to take me in I ended up with a very special woman. She spoke a bit of Tigrayan and took me in for two weeks. The tension in the streets was really bad. Even in the church we were called Juntas and compared to Satan. They said: ‘A juntas is Satan; Satan is even better than a Junta’. Everybody turned their back on me. Former friends from university, my professors, and the church. One day I received a call from the university they told me to come to pick up my certificate. When I arrived at the university, they told me to come back the next day. I returned to the house without my certificate and got stopped by two policemen. They asked for my ID card and when I showed it to them, they told me it was fake, because I am a ‘Junta’. They slept me, arrested me, and took me to prison.”

The UN Security Council expressed concern over reports of arbitrary detentions and enforced disappearances of ethnic Tigrayans in Addis Ababa in a report published on the 26th of August 2021.

Goitom: From Mahbere Dego to Addis Ababa

Goitom: “The TPLF was recruiting young men to fight Eritrean and Amhara militia in Mahbere Dego. I decided to flee to Axum. My brother lived there and was working at the University Teaching and Referral Hospital. I found my brother in Axum, but when I arrived on the 20th of November 2020 Eritrean and Ethiopian soldiers were attacking Axum from all sides of the border via Shire. My brother took me into hiding in his place until 4 am in the morning. Together we ran from the city into the rural area where we stayed in a hiding place. A man* brought us food. He assumed he was safer, since only the youngsters were recruited by the TPLF to fight. From the desert we fled to Abeba Yohannes, which is more than four hours of walking from Axum. In Abeba Yohannes it was not safe either. On Wednesday afternoon the 9th of December 2020 Eritrean soldiers were attacking Abeba Yohannes and Mahbere Dego from a distance via Adwa, Axum and Adet by using drones and heavy artillery. They killed anyone that was in the picture. On the 10th of December they arrived in the towns. I had to run into the mountains with a friend and a group of people. We kept running trying to get away from the drones and the heavy artillery aiming to kill us. We tried to dodge the shelling by running through bushes and behind trees. There was a mother running with her daughter. First the legs of the mother were blown away from underneath and then they blew of her head. The daughter lost both of her legs.” Goitom is crying when he is telling me this: “She was just a kid, her mother died, but I couldn’t help her, otherwise I would be killed. My friend who I was running with got killed in front of my eyes after that.” In the end Goitom ended up alone, everybody he had been running with was killed.

Amnesty International found out that Eritrean troop’s systematically massacred hundreds of unarmed civilians in Axum from the 28th till 29th of November 2020.

“I found refuge in a small church where I hid and laid down until the morning. In the morning people from the church started walking in and asked me what I was doing there. I told them I fled the war. A kind man from the church brought me food from the village nearby and invited me into his home. I left and stayed in the mountains for a week. I wanted to go home but my village was flooded with Ethiopian and Eritrean soldiers. In the end I went into hiding in the basement of my aunt and cousin in Muzena for two weeks, where it was relatively safe. However, a few days later fighting started in Muzena as well. Ethiopian soldiers knocked door to door to execute people. My cousin Hadush who was 24 years old stayed in the house while I was hiding in the basement. He thought he would be safer than me because he didn’t flee his home and when they knocked the door he went outside, scared that otherwise they would find me. They took him and 72 other young Tigrayan men from the neighboring villages, into the mountains of Mahbere Dego where they executed all of them.”

Bellingcat, Newsy and BBC Africa Eye worked together to make a reconstruction of videos of the Mahbere Dego massacre. They identified soldiers speaking Amharic in the uniform of the Ethiopian National Defense Force executing Tigrayan civilians in the mountains. In the videos becomes clear Tigrayan civilians are being pushed off the cliff or executed by bullets. The BBC asked for clarification to the Ethiopian Government which stated that ‘social media posts cannot be taken as evidence’.

Massacre Mahbere Dego: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X_4EjeVxMFM&t=38s

“After my cousin was executed, I did not want to live anymore, I wanted to give up and leave the house. After three days I decided to leave, even though Ethiopian and Eritrean soldiers were in the mountains nearby, kidnapping and killing all the young men they could find. My aunt couldn’t stop crying: ‘I already lost my son. You need to stay here now’. I stayed a bit but then left to the desert, since my homeplace was not safe. They were killing and kidnapping young men there as well every single day. In the end I made it to Mahbere Dego and left for Mekelle by feet to the university with a friend of mine. I had no ID-card, so I used my student card. In Mekelle It was not safe either. I ended up going from Mekelle to the university campus of Addis Ababa. I had no place to go but I figured I would be safest at the campus. But when my fellow students and teachers found out I was from Tigray they yelled at me: ‘Why are you still alive! You are a Junta you should die! They should kill all of you!’ I only survived because of one professor and one friend, they are both from Oromo decedent and supported me since the Oromo people have been in fight with the federal government as well. At night my friend protected me from the other students that were sleeping in the dorm. On the 25th of September 2021 there was graduation day. People were celebrating with their families while I was hiding outside on the campus square so no one could see me. Only students and teachers had told authorities I was there, at which three policemen came up to me asked for my ID card, put me in handcuffs and arrested me.”

Prison

Selam: Beatings and rapes

Selam: “I was captured in two different prisons. The first time they took me to a governmental primary school where they were locking up Tigrayans. We had to sleep on the floor and weren’t allowed outside. My co-workers had to come to bring me food. In the end I was released after my sister paid for my freedom. After I was released, I got arrested again and was taken to a prison where men and women got separated. I can’t tell you everything that had happened to me or the other women. It was too traumatic. We slept on the floor, there were young women, elder women, and pregnant women. We all received one small piece of bread a day. There was sexual harassment and beatings. Sometimes the guards would call you to the office. In the office they were abusing the women. One woman gave birth insight the prison. After three months I was released after my sister paid again. Another sister who lives in the United States found out that many of my family members have been abducted by Eritrean troops in Abi Daero and that I had been in prison for the second time. She told me it was not safe for me to stay in Ethiopia and that I had to leave. She paid smugglers to take me out of Ethiopia.”

Atsbha: Torture

Atsbha: “I got arrested from my bed at midnight and thrown in prison. For over a month I stayed in a small room of approximately 20 square meters with a group of 50 people. Almost all prisoners were Tigrayan. The policemen tortured me, undermining my human values and ethnicity. Government media were spreading ethnic based hate speeches and abuses that directly affected me and my family. We were neglected from the neighborhood. I was living in a country hiding myself with a low profile. The fears I was facing were disturbing on a daily basis. I was limited to travel from area to area and could not deliver my assignments in the country. Finally, I got the ‘luck’ when an international conference was held in the Netherlands that I could attend to, and I’ve stayed here since. I’m safe in the Netherlands now, but this experience gave me a trauma that I struggle to forget. Every time there is a knock on my door, I fear that there is a policeman coming to arrested me without reason. My wife and my children are in Addis Ababa. I arrived in the Netherlands on 18th June 2022. From that moment they have been harassing my wife. Police arrested my wife two times after I left to ask her where I am. They’ve put her in prison and interrogated her. She told them I am on a work trip, and they left her but said to be coming back to search for me and arrest me. She has been living in fear since. And she has not been showing her face since that time in public. My kids are now asking my wife: ‘Where Is Papa?’ They miss me and always worry for my safety and security. Leaving everything behind because of your ethnicity and conflict became a headache for me.”

Goitom: ‘We will kill you today’

Goitom: “The police officers took me from the university to the police station. When I arrived, they threw me in prison with nine other Tigrayans for three months. They tortured me and made the same joke over and over again: ‘we are going to kill you today’. When the TPLF got closer to Addis Ababa, they told me, ‘we will now really kill you’. After the TPLF withdrew to Tigray they let me go, telling me I was a student. I went straight back to university after I was released since I had nowhere else to go. I looked for the one professor that had been good to me and asked him for help. When I told him I did an internship for Heineken he called the manager and asked him to give me a job. I got a 3-month trial period but when the manager figured out, I am Tigrayan they fired me, under the excuse of ‘bad work’. After I was fired at Heineken I was arrested again and put back in prison. This time a relative paid to release me and helped to flee the country. Now I’m in Netherlands and don’t know where my friends and family are. I haven’t heard from them since the war. I don’t know if they’re alive.”

Robel: ‘You’re going to die here, silently’

Robel: “I was arrested on my way back home from university and was thrown into a closed area with lots of boys. It was kind of a container in Addis Ababa. Here I got transferred to a police station. They threatened me and told me not to lie about my origin. But I did, which I think saved my life. I told them I have been living in Addis Ababa since 2018 and that I didn’t know my father so that even if I have a Tigrayan name they would not think I was raised in Tigray. They didn’t kill me, but they let me stay outside all night with the others. I was really afraid and crying by that time. After surviving everything in Tigray I still got locked up in Addis Ababa. The next day the policemen transferred me to the Aba Samuel Prison, one hour drive from Addis Ababa. The prison was really big and full of innocent people, I’ve even seen priests and bishops. I was afraid they would take a picture of my face and portray me on the news as a prisoner of war. They do this randomly even if you’re innocent to show their power and pretend to have arrested war criminals. After that you don’t have a life anymore. In the Aba Samuel prison, we got one small piece of bread which we had to eat for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I stayed there for two weeks.”

Robel and others* in the Aba Samuel Prison

“Then I got transferred again. This time to Mizan Aman Prison nearby the city Aman. The prison was in the middle of the forest. Here I was very scared. We were with 170 people in one room of less than 65 square meter. It was extremely hot and there were a just a few very tiny windows. Sometimes they would take us outside and beat us up. There were federal police and people in uniform from the Addis Ababa police force. We were tortured. I also got Malaria and was convinced I was going to die. In the forests around us there were lots of holes in the ground. One of the prisoners died, people were crying and mourning. They were yelling at us to shut up. One day a big general came to visit us by helicopter. His name was Colonel Getnet Adane. He told us: ‘You’re going to die here silently. We don’t waste our bullets on you.’ After he said that the Ethiopian federal army came to beat us up. This place really changed me, I’m now afraid of the smallest things. After three months of staying there lots of men had died in the Mizan Aman prison. They took half of the prisoners that were still alive including me. I thought I would finally be released. But we got transferred back to the Aba Samuel prison. I still had Malaria and was very sick. They told me: ‘If you pay, we release you.’ I had to call him, my cousin. My cousin lives in Saudi Arabia. He had told me to call him at the beginning of the war if anything would happen to me. I memorized his phone number and called: ‘I am in prison; they ask for money. If I don’t leave here, I will die’. He paid for me.”

- Colonel Getnet Adane is also known as the military spokesman of the ENDF.

- Aba Samuel prison is a high security prison.

Mizan Aman Prison, source Robel: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/03XeDspw2TU

“After I was released from the Aba Samuel prison people in Addis Ababa were threatening me in the street. They told me: ‘Give me money or I will make sure they arrest you.’ I sheltered in different places in Addis Ababa and decided to go to Kirkos. But they had roadblocks in search of Tigrayans. I got stopped before, but I could always manage to run away. This time it was impossible because there were too many soldiers. They arrested me again and took me to another prison around Kirkos. I started crying and gave up. This time another soldier came to me and said: ‘If you pay money, we will let you go’. I called my cousin again. This time he had to pay 20.000 Ethiopian Birr to release me. I begged my family in Saudi-Arabia to take me outside to another country. They told me we will manage something for you. And one night I received a call: ‘We will leave tonight’. Robel has been in seven different prisons during the war.”

In the report from the OCHR and the EHVR is written following: ‘Witnesses and victims testified to the ill-treatment of captured Tigray forces in Adi Gudem, Awash military camp, Adigrat, and Kedamay Weyane police station in Mekelle. Most of those in detention in Kedamay Weyane police station were former members of the TSF or civilians suspected of providing food and other support to them. One woman, who was a captured Tigrayan fighter, described how she and another friend arrested with her were tortured by the ENDF using wooden sticks at Awash military camp in Mekelle. She said soldiers also tortured prisoners at the camp with electric cables and plastic covered metal rods and wooden sticks. ENDF also abused prisoners by holding guns to their heads. Another man arrested on suspicion of providing food to Tigray forces described how his hands were tied behind his back for three hours and how he was later reportedly tortured by the ENDF with electric cables at a military camp in Adigrat.’ In the report is written how captured TPLF forces or civilians that are involved in helping the TPLF were captured. Reuters discovered more than a dozen prisons all around Ethiopia with at least 18.000 Tigrayan civilians arrested and detained, including women and children.

Future

I reached out to the UNHCR Ethiopia on the future of investigations on the war crimes committed in Ethiopia. After initial communication there was no further official response due to humanitarian emergencies in Ethiopia and Sudan. I also reached out to the UN World Food Program (WFP) on the allegations of looting of food trucks and storages by Eritrean militia. There was no response. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Geneva did not want to respond on record on my question if there would be an independent investigation for genocide in Ethiopia.

“Why isn’t the Tigray Genocide recognized by the world as Genocide? The dictatorial Ethiopian government, soldiers from Eritrea, drones from the United Arab Emirates and Turkey, and local special forces have collectively killed people of Tigray. I’m not saying the TPLF is innocent. The authorities of the TPLF are like dictators; they only care about their power. The Tigray people’s human rights have been violated, they don’t care about the people who have been killed by Ethiopian and Eritrean military, and they don’t like to respond to questions from the public. Silent genocide has been committed upon the people of Tigray.” – Goitom

The UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide states that genocide means the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such:

Killing members of a group:

Researcher Jan Nyssen investigated the war in Tigray through satellite images and concluded 600.000 Tigrayan civilians have been killed in the war over a time period of 2 years in 2022. However, official numbers have not been available yet since the Ethiopian government does not allow international organization full access to the area.

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of a group:

Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International conducted a joint investigation in which they discovered torture, rape, sexual slavery, and other inhumane acts against the people of Tigray:

- 288 cases of gender based violence were registered from February till April 2022, the health facilities in Tigray

- 852 cases of survivors of rape were reported between November and December 2022 at the Tigray Health Bureau after the peace deal was signed in November 2022.

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction on whole or in part:

The Tigray Health Bureau reports the collapse of the health care system in Tigray due to the deliberate destruction, looting and vandalization of various health facilities in Tigray. The DX Open Network, a security research organization based in Britain discovered at least 508 structures in Tigray had been destroyed by fire in the week of 25th February 2021 in and around Gijet, Tigray. Tigray is a mainly rural region and agriculture contributes to more than half of the regional GDP, of which 36% is from crop production and 21% of livestock and forestry. The Tigray Bureau of Agriculture and Natural Resources reported that the seed development sector has been looted, burned, and mixed with sand in rural areas. Crop-production has been burned, looted, and damaged by tanks and other vehicles. Livestock such as animals, animal feed and resources have been slaughtered, looted, and destroyed. Natural resources such as watersheds have been damaged and destroyed. More than 40% of the 1.9 million draft oxen have been stolen or slaughtered and more than 90% of the 1.990 farm tractors in Tigray were looted or destroyed.

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group and forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

* Identity anonymous for safety reasons.

** Some faces were blurred for safety reasons.