In the southwest of France, the river Bidasoa forms a natural frontier with Spain. Since 2018, several migrants have died trying to cross it.

While the European Union boasts that, within the union, there are no borders, and that any citizen can move freely between countries, the reality is not always like that. The frontier between France and Spain has been closed for years without anyone doing anything about it. Recently, the French government has been forced to open it, as it was not complying with the regulations. “The government renewed the decree every six months to close the border, and there were always police controlling it. They said it was a measure against terrorism or because of covid, but we know that they were measures against migrants”, explains Amaia Fontang, a volunteer of the federation Bidasoa Etorkinekin (Bidasoa with migrants).

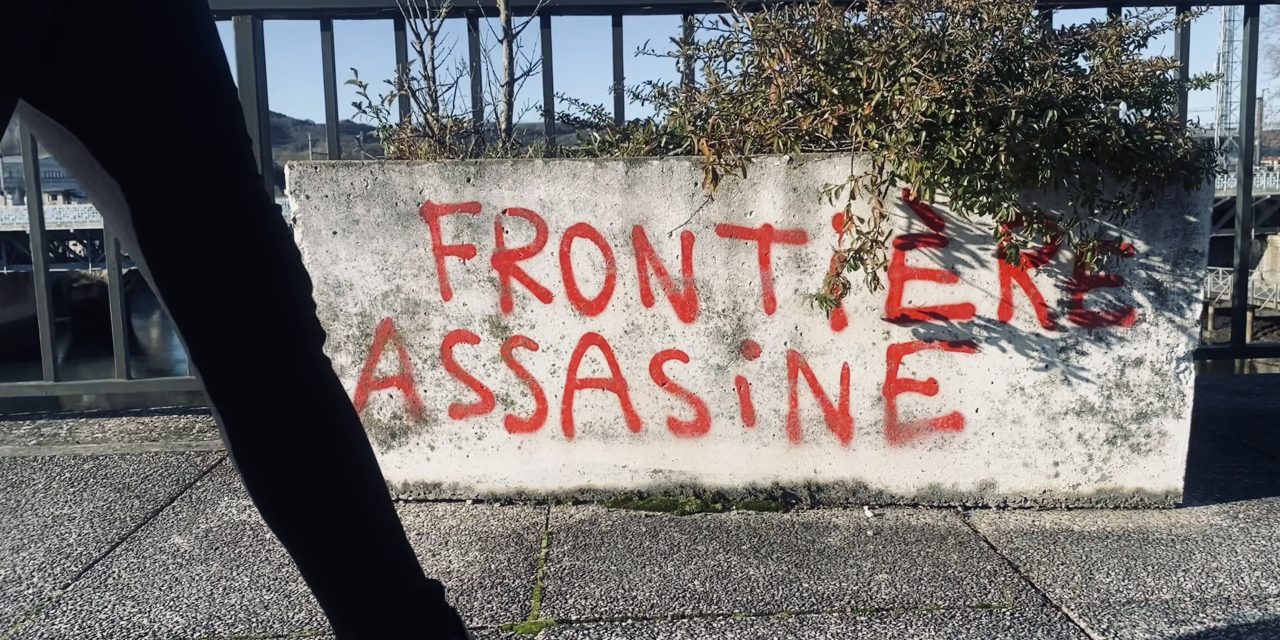

Police controls and protest graffiti on the Santiago Bridge (Spain/France border). Photos: Ane Echandi

Although the frontier is now open, the situation is not easy yet. There is still a lot of police control, often camouflaged so as not to be recognised. “Large police presence and border controls force migrants to take risks. That is the reason for the deaths, not the river”, says Amaia Fontang. Not only the border, but Hendaye, the town next to the border is full of police. “We call it migrant hunting. They are everywhere: at the train station, at the bus station, on the railway tracks, on the motorway…”, explains Fontang.

Since 2018, ten people have died trying to cross the border between Spain and France: Seven of them drowned in the Bidasoa river, and the other three lost their lives in other circumstances. A representative of SOS racism states in Xavier Bosch’s master’s thesis (“The violation of the rights of migrants in transit at internal borders of the European Union”) that it is unacceptable for a person to drown while crossing a border within the Schengen area, due, moreover, to controls on the routes used by everyone, but closed to certain profiles of migrants.

Bidasoa river. Photos: Ane Echandi

2018, a turning point year

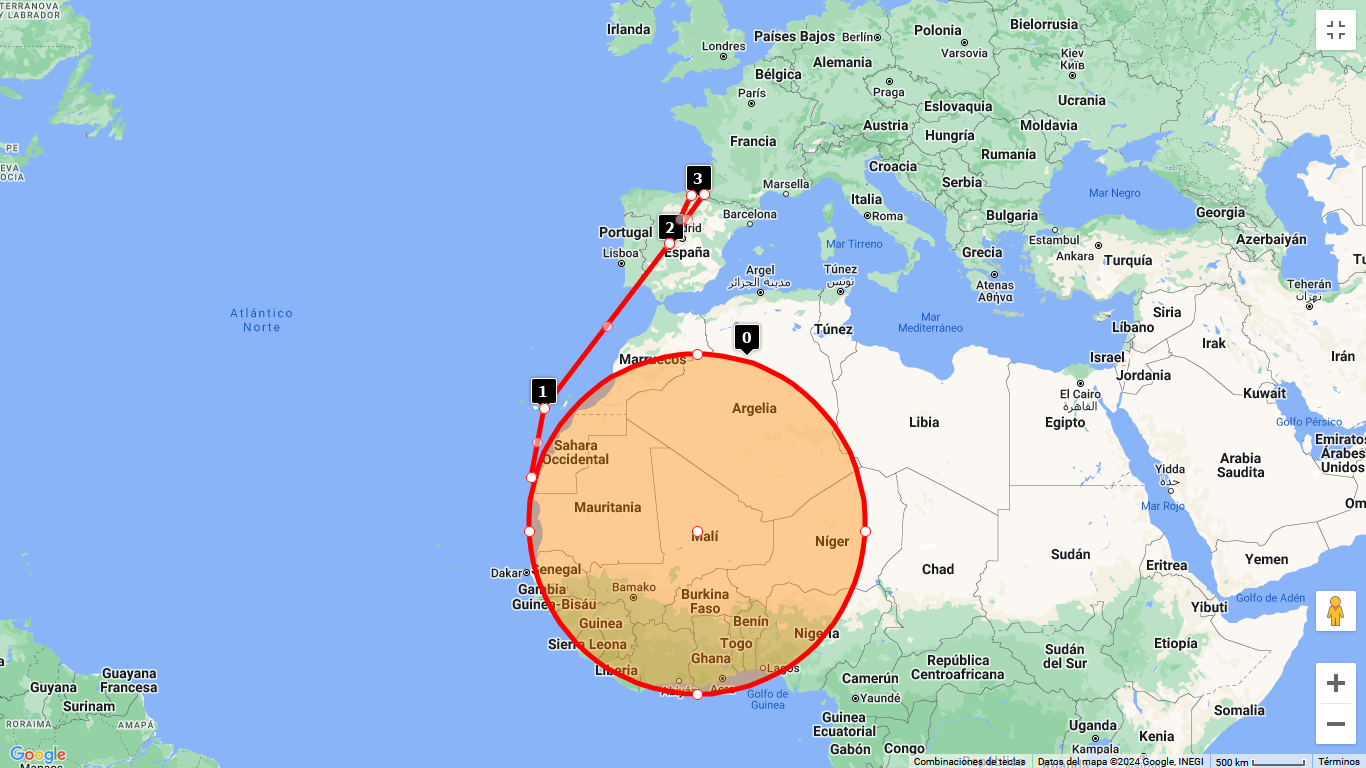

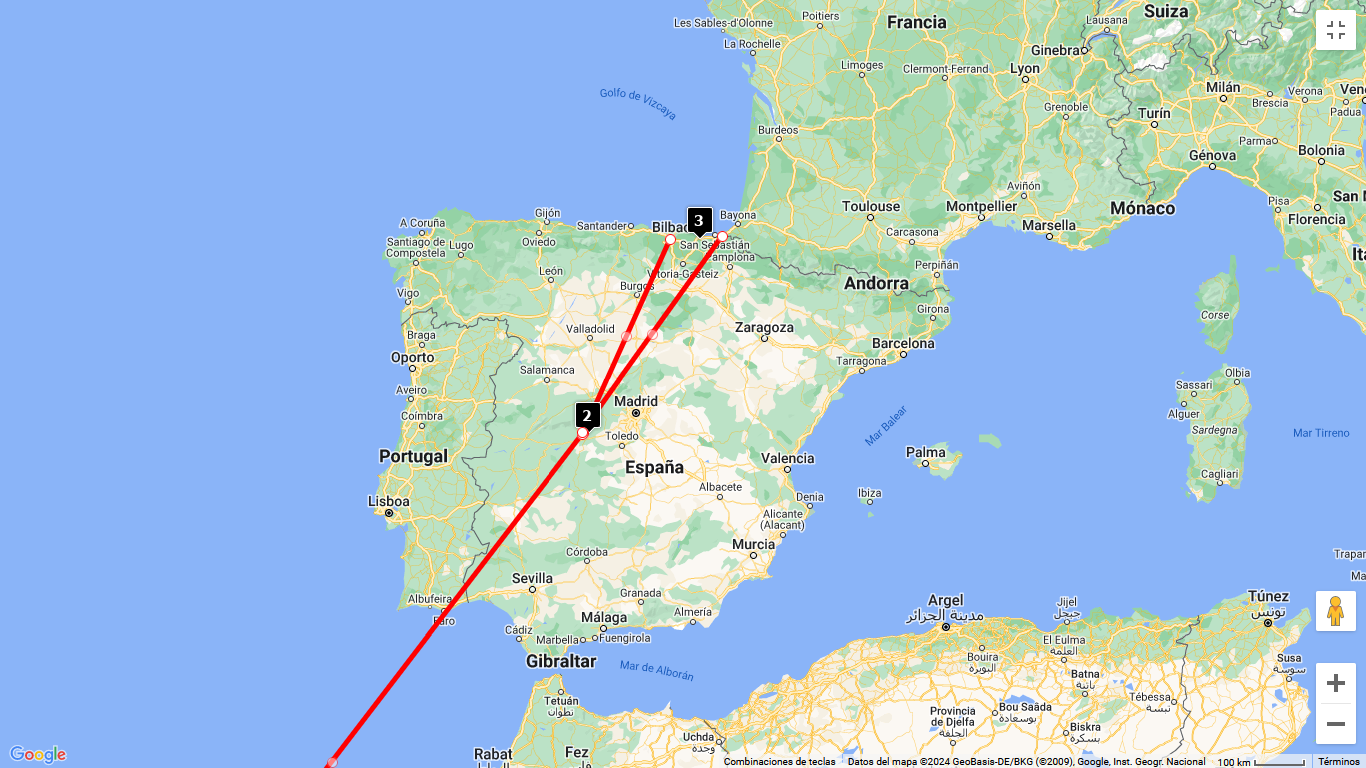

From this year onwards, many more migrants started to arrive in northern spain. This is because in 2018 the route from Libya to Italy was closed, so many migrants choose to take a different way to reach Europe. Instead of going through Italy, many people started going through Morocco. They arrived at the Canary Islands first, and from there they were sent to the peninsula.

Migration route. Image: self-produced.

Most of them come from West Africa and speak French. That is why they do not want to stay in Spain and continue their way to France. After arriving on the peninsula, they travel north, usually to Bilbao or Irun.

The inhabitants of Bayonne, a city in the south-west of France, seeing that more and more migrants were arriving in the city, spending their nights on the streets with nowhere to go, decided that they had to do something about it.

The Bidasoa Etorkinekin group already existed at that time, but in 2018 it became more active, in order to find a solution to the situation they were experiencing. While etorkinekin focuses on helping all migrants in general, at that time another organisation was created to help migrants in transit. The number of people was so large that the existing group was not able to help everyone. This is how Diakite was born, named after one of the first young people who arrived in Bayonne.

When they arrived in the city migrants gathered in a square called Place des Basques. The buses left from there, so they spent the night in the square to catch the bus the next morning. “We held two main events in September of that year: First, we did a press conference in the Place des Basques, together with organisations from Spain, to ask the institutions and public authorities to fulfil their responsibilities and to create a transit centre. Then, we did another action in the town hall of Bayonne. We went inside the building to denounce the situation and, again, to ask for a transit centre for the people who were spending the nights in the street”, explains Amaia Fontang. The response came quickly, and within two/three weeks they opened a transit centre called “Pausa”.

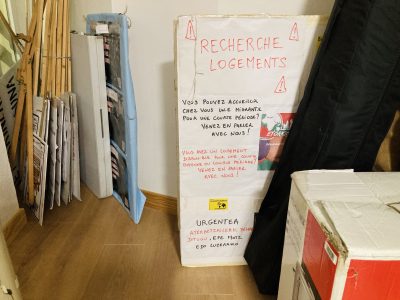

Pausa center in Bayonne. Photos: Ane Echandi

The transit centre is a place where migrants spend two/three nights before continuing their journey. Most people who arrive in Bayonne do not want to stay there, as they think that in bigger cities they will have more opportunities and it will be easier for them to find work.

At this point, it is important to explain what transit migration or migrants in transit is. However, many academics and researchers in this area agree that it is a very difficult concept to define. Xavier Bosch explains it this way: “There is no “canonical” definition of what it means to be a migrant in transit. This is explicit in the 2016 Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), which understands “transit migration” as a term that refers to the temporary stay of migrants in one or more countries with the aim of reaching another country to settle, with an emphasis on “temporariness” (OHCHR, 2016, p. 3)”.

Volunteers also persecuted

The objective of the migrants once they are in French territory is to reach Bayonne. The transit centre “Pausa” is there, and once they arrive in the city they cannot be sent back to Spain. Because of the police controls it is often very difficult for them to get to Bayonne, so many people help them and take them by car. Although it is completely legal, this causes problems for the people who help them as well. Last July they stopped a car that was taking migrants to Bayonne. Next day the police went to their house to do a search. They searched three houses and it was known that people were persecuted for 8 months. The police had put GPS under the cars and also spied on the phones. “Helping them cross the border is not legal, but once they have crossed it, taking them in your car does not break the law”, says Aintzane Lasarte, member of Bidasoa Etorkinekin. So there is also a police operation against the volunteers.

The work of organisations and volunteers is very important, as without them the journey of migrants would be much more difficult. But the question is inevitable: Are these people doing the work that should be done by the institutions? “It is a key question, we ask ourselves this question every day. Our aim is not to do the work of the institutions, but to do what is necessary under the circumstances, and denounce it at the same time. Being aware of the situation, we have no other choice”, claims Fontang. The denouncing aspect is very important for them. “Our actions are not humanitarian or charitable, they are solidarity actions that are directly related to the protest”. In addition to helping migrants, they organise numerous demonstrations to denounce the situation.

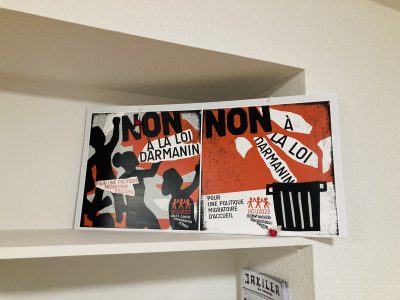

New migration law, stricter than ever

The French government has recently approved a new migration law. This law has been very controversial, as it has tightened many points compared to the previous law. “It is the toughest law there has been in recent years. We are very worried, and the future for migrants is very dark”, explains Fontang. Lutxi Bortairu, a member of the Diakite association, says that this law will not stop them from continuing to come: “Europe is totally closing itself off, making walls everywhere, but the law is not going to change anything. They want to come and they will keep coming”. She explains that many of them have no other choice: “They are escaping from war, torture, misery…. And they will soon be escaping the consequences of climate change too”.

One change of the new law that has greatly angered the public, and especially doctors, is the elimination of the state medical aid. This allows undocumented people who have been in France for less than three months to receive free medical aid. Bortairu thinks that removing this aid does not make any sense: “It is much better to treat someone in prevention or when they have just fallen ill, than not to treat them and wait until they are in a worse situation. In this case, the cost will be much higher”. Many doctors have taken a stand against this measure, and have made it clear that they will continue to see everyone in their clinics.

It is clear that migrants do not have an easy future ahead of them, and laws like this one show that instead of evolving, in many aspects, Europe is going backwards. Bortairu argues that this is about human rights: “The right to migrate is an international right. Everyone has the right to change countries, to travel around the world, to go wherever they want”.