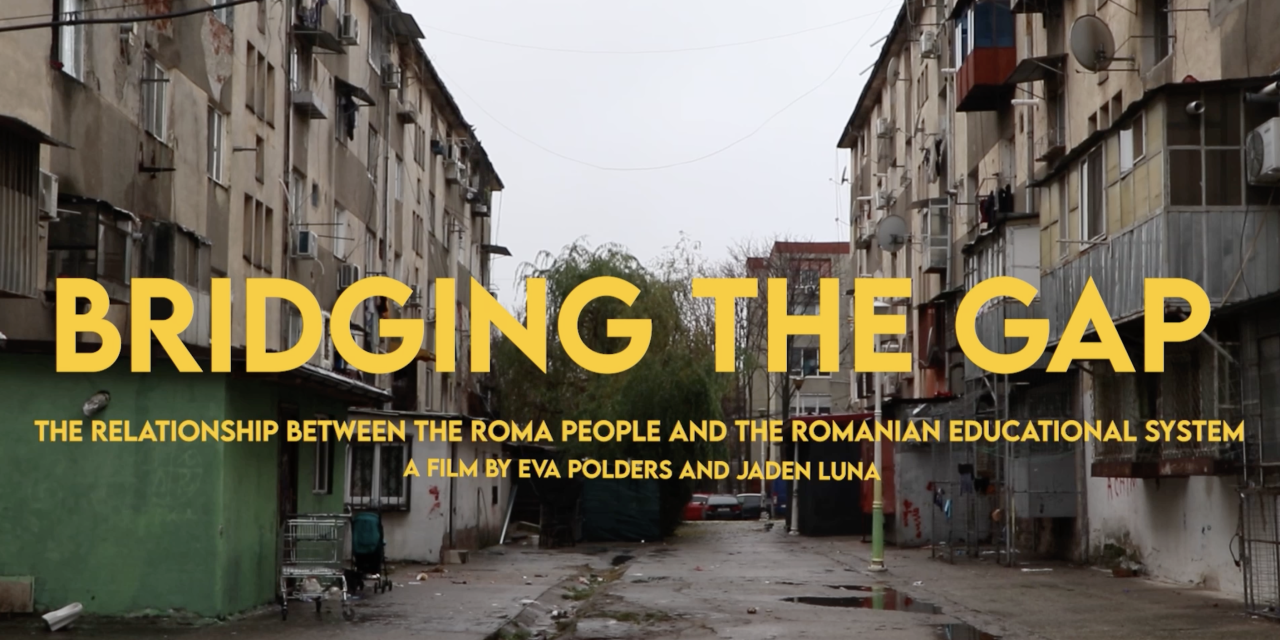

The Roma community in Romania is a community that has been looked down upon for hundreds of years. Historically marginalized, the Roma population remains trapped in cycles of poverty and exclusion, with limited progress toward improving their circumstances. Although efforts have been made to address these issues, the community has a very low educational rate. Could there be a historical reason as to why the Roma have been lowly represented in the educational system and why has the country of Romania still not fully accepted them?

Parents with their kids on the way to the neighbourhood school in Ferrentari, Bucharest

The Roma people, commonly referred to as țigani in Romania, have faced centuries of marginalization. Researcher Danckaersnotes that the term țigani originates from the Greek word Athiganoi, meaning “untouchable” or “impure,” reflecting the discriminatory perception of the Roma as outside societal norms. Upon their arrival in the Byzantine Empire, they were wrongly associated with this sect, and the label became a symbol of deviance. Similarly, the term “gypsy,” commonly used in Western Europe, stems from the mistaken belief that the Roma originated in Egypt. According to linguists Kuiken and Van Der Linden, while “gypsy” is less overtly derogatory than țigani, it still perpetuates harmful stereotypes about the Roma.

They saw me as one of the good ones. Gabriel Zorila

Gabriel Zorila is laughing while shying away from the camera

‘That’s not who I am and also not who I ever was. I always worked as hard as I could and never begged for money. As Roma we always have to work twice as hard, to prove that we were just as good, not better, just good. When I was younger, I was able to go to school and get a good education. When it was time for me to go to university, I was only able to attend classes for one semester. After that I had to quit to support my family.’ says Gabriel Zorila, Roma and a parent of two children.

For nearly five centuries,the Roma endured brutal enslavement in the Romanian Principalities, enriching landowners, the Orthodox Church, and the aristocracy. Historian Constantin Bălăceanu Stolnici explains that Romania was unique in Europe for maintaining a formal system of enslavement into the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, long after other parts of the continent had shifted slavery to overseas colonies. Foreign observers like Comte d’Antraigues were appalled by the inhumane conditions, describing Roma as being treated worse than livestock.

Roma are not lazy, Roma want to work, Romas are doctors. We have that here as well Gabriel Zorila

‘When I was growing up, there was nothing in the history books about the Roma-community.’ tells Zorila, ‘Nobody knew how much my people have had to go through. Hundreds of years of slavery and no one knew about it. I think this is part of the reason why people do not like the Roma. They simply do not understand how my community works. I think it is very sad that it has taken so long for Roma history to be put in history books that schools have to teach. Now we have the internet and we can look up everything we want. I think that helps with the understanding of us. We are not bad people, we are just trying to get the same out of life as everyone else does.’

The historical reality of Roma slavery is largely absent from Romanian history textbooks, according to Myers, McGhee, and Bhopal, contributing to a lack of public awareness and understanding of this dark chapter. Education remains one of the most pressing challenges for the Roma community. Researchers Scholten and Vogelaarh highlight that despite compulsory education laws for children aged 6 to 17, many Roma children are excluded from schooling due to a lack of birth registration, which prevents them from accessing essential public services. Financial barriers also complicate access, with Roma families unable to afford school supplies or contribute to class budgets, as noted by Tudosie. Systemic discrimination in the classroom results in the segregation of Roma children, with many placed in classes for those with mental disabilities, which stigmatizes them and limits their future opportunities. Eurocities explains that language barriers further exacerbate these challenges, as 70% of Roma children struggle to understand the language of instruction.

An abandoned stroller stands alone without going anywhere.

‘I had the chance of getting a good education. I was very lucky. My parents always wanted me to get a good education so that I would be able to choose the best options that this life had to offer me. In university I was one of the only Roma, there people didn’t look at me in a weird way. But I think that was only because I got such good grades, that they did not have a reason to doubt me. A lot of people think Roma are not educated. Let me be clear: there are Roma very much educated and education is important. On the other hand, education is not only sending your kids to school and them learning things. So many more things will be added when your kid goes to school. Things that poor families, for instance, don’t allow. So, we do not talk about the Roma families but about the poor families. No one wants for their kids to get bullied and get a very bad experience at school. It is always still up for the parents to decide what to do.’ says Ionela Pădure, a Roma and informal teacher.

Everyone says that education is free. Wrong! Education is not free. Roma parents do not want their kid to get bullied, so they don't send them to school. Ionela Pădure

Romania’s national strategy for Roma inclusion, introduced in 2001, aimed to address these systemic barriers by providing identity papers, reserving school spots, and enforcing anti-discrimination laws. Although the country has tried to improve, the lack of recognition for the Romani language in education remains a significant issue. As pointed out by researchers Kuiken and Van Der Linden, although Romanian law guarantees minority groups the right to education in their mother tongue, this provision does not apply to Romani, resulting in the alienation of Roma children and hindering their educational success. Cultural factors within the Roma community also play a significant role in shaping education outcomes. Pharos Expertise Center explains that traditional family values, including early marriage, often take precedence over formal education for many Roma children. This is particularly true for Roma girls, who are more likely to leave school early to assume domestic roles.

‘The Roma community is still very much outdated. They usually don’t go to school or take their children out of the educational system at a very young age. I see this in my school as well’, says the director of Bucharest middle school 143, Dan Alexandru-Chita. ‘Girls usually just go until they are 13. Usually the boys stay for much longer. Just until they have a degree that they can get a decent job with, so that they can sustain the family. The Roma children just have to come to school and follow the drills if they want to get a good education. If they don’t, then they will stay stuck in the place that they are in.’

Expanding access to free and high-quality education for every child is something that Romania as a whole has to work on. Incorporating Romani language in the curriculum could help bridge the gap between Roma children and the Romanian education system. Despite decades of policy initiatives, the Roma community remains one of Romania’s most marginalized groups. Addressing these challenges requires a commitment from the government, civil society, and the Roma community itself. Only then can a better future be made a reality.