“Who is telling whose story” Frederik Biemans -former head of programming and exhibition at Humanity House- asks herself. Even if immigration conquers the media space it deserves, the question of refugees representation remains unanswered. NGOs have a long-standing tradition of using highly charged emotional images to portray scenarios of poverty, hunger and violence in so-called Third World countries. But the overload of this heart-breaking imagery is taking its toll on those communities it sought to defend: the general public is growing desensitized to humanitarian crises. The call for new ways of raising awareness has not gone unnoticed, as a wide array of curators and artists are taking upon themselves the challenge to reinvent the way refugees are represented. Why artists? “Art is where society experiments, art is a way to reflect as a society” responds Frederiek Biemans, “a way to digest things from the past.” She refers to how the European history of colonialism is now being reinterpreted in a critical light also thanks to the impulse of cultural institutions. The momentum in support of oppressed communities is inevitably reflected in the increasing spaces dedicated to their art in museums and galleries. And the influence flows both ways. “Art highlights perspectives that are often excluded from mainstream media and consciousness, in a very relatable way” adds Saskia Stolz, creative director of Sazza and Power of Art House, “Art is our universal language.”

A new visual language is making its way through the clutter of stereotyped images of immigrants that have dominated the Western media for decades. The starting point lies in the role that migrants themselves play in the process: instead of objects of sympathy, they become the subjects of their own narrative. In 2016 Humanity House, an initiative of the Dutch Red Cross based in The Hague, enriched its permanent exhibition with the stories of eight refugees who had to flee their countries for different reasons. Lidija, Desbele, Aiham, Bruce, Shaza, Yvonne, Ram and Akhrat could share their experience with the audience in their own words. Interviews took place in an intimate environment and the recordings were exhibited in the museum. Frederiek mentions the reactions of school children; how they would listen captivated to these real-life stories, eyes glued to the narrators on the screens. As refugees leave behind their place in pitiful images to gain a new face and a strong voice the result is quite impactful. “Everyone came out slightly overwhelmed, because it’s something that you know and you don’t know” continues Frederiek “When you hear it like that you realise it’s something you don’t know.”

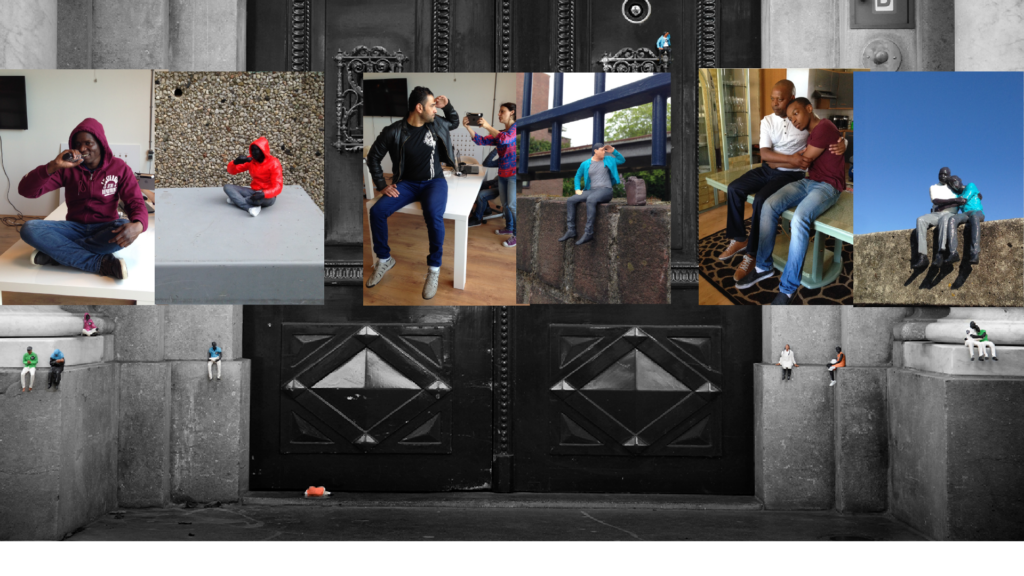

Moving People -Power of Art House

Nevertheless, there is no denying the gap still existing between the general public and the arts. Curators also face the challenge of bridging the gap between the reality of displacement and hardship of immigrants and the relatively comfortable world of the Western audience. Power of Art House brings art to the public space to fill the gap. “Those of us in first-world countries like the Netherlands have a responsibility to understand how we are implicated in a global political and economic system that privileges a few and causes suffering to people we haven’t even met” says Saskia. Power of Art House is an Amsterdam-based art platform, which built its reputation with several artistic interventions on socio-political issues. In 2015 the project Moving People was launched. Ten refugees became 10,010 handmade figures of about 11 centimetres thanks to 3D scans and printing. These miniatures, initially placed around Amsterdam and The Hague, ended up travelling to several international locations. Beside being moved, they were also aimed at moving the audience: they carried a sticker linked to the website where the life stories of the refugees could be read. The use of the public space allowed this project to acquire a visibility and an international media coverage not accessible behind the walls of a museum or gallery.

What unites these two examples of so-called artivism, the meeting point of art and activism, is their aim at empowerment. Refugees, as other often misrepresented communities, are empowered to find their voice. What Frederiek Biemans identifies as a “new push” of socially and politically engaged art can open up to a new more inclusive visual language. A language where there are no victims but individuals who own their life and the right to share it.