In the heart of Romania lies the city of Cluj-Napoca. Once part of the powerful Hungarian Kingdom, now Cluj has belonged to Romania for the past 105 years. But what about the Hungarians, the largest minority still living there? Do they feel at home in a country where they were born but to which their roots do not belong?

Cluj-Napoca, a city with no less than 286,598 inhabitants, located almost in the center of Romania, has a rich history, a Hungarian history. Cluj (short for Cluj-Napoca) was part of the former Hungarian Kingdom until the end of the First World War. This changed with the signing of the Treaty of Trianon in 1920, which helped to end the war. As a result, the entire region of Transylvania, including Cluj, became part of Romania. To this day, that history remains visible, not only in the architecture, language, and culture, but especially in the people of Cluj.

The Hungarian population in Cluj is steadily declining. In 2023, only 11.3% of the city’s residents were Hungarian. Although they remain the second-largest ethnic group, their numbers have significantly decreased over the years. Along with that, the feeling of being at home in Cluj is also fading for many Hungarians.

Strong Culture

After the Treaty of Trianon, Romanianizing became a major policy. Many Hungarian institutions were replaced or adjusted. Despite this demographic shift, Hungarian culture remains visible in Cluj. Two important cultural landmarks in the city are the State Opera and the Hungarian Theatre. The State Opera (Magyar Állami Operaház) and the Cluj Theatre (Kolozsvári Állami Színház) are the oldest and most prestigious Hungarian-language cultural institutions outside of Hungary. They present operas, plays, and concerts exclusively in Hungarian, and are highly valued by the Hungarian community. There is also a Hungarian City hall and a reformed church that is still in its old state.

Hungarian Legacy

“It makes them feel more at home,” says Balázs Bodolai, a Romanian Hungarian actor at the Cluj Theatre. “I speak with pride in my own language. I may have lived my entire life in Romania, but both of my parents are Hungarian. I keep their legacy alive by speaking their language on stage.” The theatre is a state-funded institution, meaning it is supported by the Romanian government. “I’m very happy that Nicușor Dan won the elections last week. Since he supports the Hungarian community, there’s a good chance that this theatre will continue to operate. He is open to minorities in Cluj. The right-wing party, led by George Simion, is not so welcoming toward us—and not just us Hungarians, but all minorities,” Bodolai explains. “It gives me an unpleasant feeling, like we’re not wanted by all Romanians. Sometimes I feel like I’m not welcome in my own country.”

Data

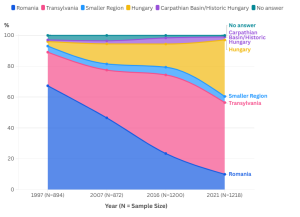

Bodolai is not alone in feeling this way. This graph shows how answers to the question “What do you consider your homeland?” have changed among ethnic Hungarians in Romania between 1997 and 2021. Fewer people now consider Romania their homeland, while more identify with Transylvania. Since 2016, an increasing number of people also identify with Hungary as their homeland. This reveals a shifting national identity and growing awareness within the minority group.

Table 1: What do you consider your homeland? – Made by Loekie Pruijn

According to Dr. Tamás Kiss, a researcher at the Romanian Institute for Research on National Minorities (ISPMN), the graph should be interpreted critically. The question “What do you consider your homeland?” can be influenced by many factors. Kiss, an expert on ethnic minorities in Romania—particularly the Hungarian community in Transylvania—contributed to collecting the data behind the graph.

“People have many reasons not to feel at home in a certain place. It’s not all about culture or language,” Kiss explains. “For example, Hungarians are often less wealthy and tend to live in the same neighborhoods. For many people, money is the main reason they don’t feel at home.” But that’s not the only reason, he adds: “Politics plays a role as well. It doesn’t help when someone is openly against you and your people, like George Simion. That doesn’t create a welcoming environment.”

The future of the Hungarian minority in Cluj remains uncertain. While the buildings, the culture, and the language are still present and strong, the question remains: what will happen to the Hungarian community in Cluj? Will the feeling of homeland ever truly return for them in Romania?