In large parts of Europe overcrowding dominates the political debate. In Bulgaria the opposite reality is unfolding. Less than an hour north of Sofia lies Lukovo, a village with dozens of houses but only a handful of residents left. Windows are shuttered, gardens overgrown, and the local school has long since closed. Lukovo is not an exception but a symptom of a broader national trend. Across the country, entire villages are falling silent as Bulgaria’s population shrinks. What remains is not destruction, but abandonment: houses still standing, waiting for people who are no longer coming back. This raises a pressing question: can Bulgaria breathe new life into its land, or has it already passed the point of no return?

A Demographic Collapse Decades in the Making

Over the past decades Bulgaria’s population has declined rapidly. From nearly eight million inhabitants in 2000, the number fell to just over 6.4 million by the end of 2024. Projections suggest a further decline of more than 20 percent by 2050. According to the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy this decrease is driven by a combination of low birth rates, high mortality, and sustained emigration since the early 1990s. In 2024 alone, Bulgaria recorded 53,428 births and 100,736 deaths, resulting in a negative natural growth. Villages like Lukovo reflect what these figures mean in practice: once viable communities gradually hollowed out as generations disappear. The numbers describe decline, but they do not capture the stillness of places where time seems to have stopped moving forward.

Leaving as a Rational Choice

For many Bulgarian these numbers translate into lived reality. Anita Dangova left Bulgaria at eighteen to study law abroad, but returned a few years ago to Bulgaria. Coming from Plovdiv rather than Sofia she saw limited prospects for a legal career. ‘If you don’t come from a rich family you’re often told you won’t be able to succeed here,’ she says. Studying abroad was an adventure, but mainly a choice dictated by circumstances. She was looking for opportunities abroad she could not get in Bulgaria. ‘To be able to build something in law, I had to move abroad. It was career opportunities, but also to get a better education.’

Emptying Villages and a Polarised Population

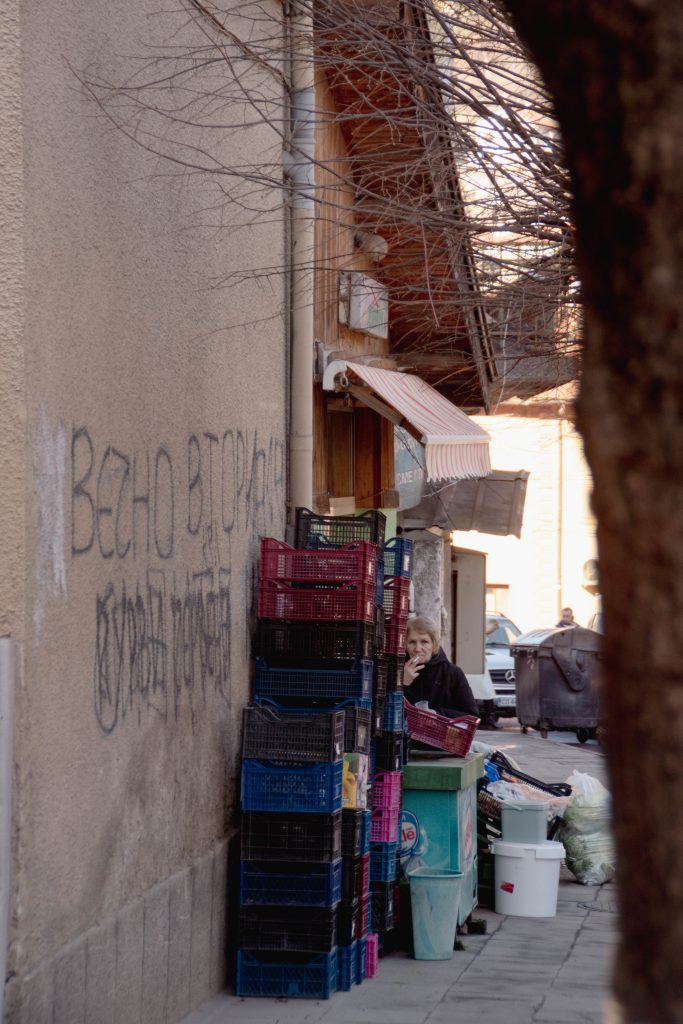

At the same time hundreds of settlements have been left without a single resident, while more than a thousand villages now count fewer than fifty inhabitants. This demographic crisis is unevenly distributed: rural and remote regions empty first and fastest. In Lukovo most houses remain structurally intact, but daily life has largely vanished. The physical presence of houses contrasts sharply with the absence of life inside them, creating a landscape that feels paused rather than alive.

According to demographers, the problem is not limited to isolated villages. ‘Remote regions are emptying the fastest, but cities are also slowly losing population,’ says Boris Kazakov, associate professor in demography at the National Institute of Geophysics, Geodesy and Geography in Sofia. ‘There are a few cities that remain relatively stable for now, such as Sofia and Plovdiv, but depopulation affects the entire country.’ The result is a sharply polarized demographic landscape, with people and economic activity increasingly concentrated in a handful of urban centers.

This polarization has tangible consequences. As populations decline, economic opportunities disappear. Local businesses close, public transport becomes unviable, and essential services such as healthcare, education, and childcare are scaled back or disappear altogether. The school in Lukovo is closed. The door has been shut for a while. Wilderness is overgrowing it. There are simply too few people left to sustain a school, or even a grocery store. Depopulation is not just a demographic process; it is a gradual erosion of the conditions needed to live a stable life.

Mapping a Shrinking Future

Professor Nadezhda Ilieva, who specializes in demographic forecasting at the National Institute of Geophysics, Geodesy and Geography in Sofia, has mapped Bulgaria’s future population decline down to the level of individual settlements. Her projections show that by 2030 and 2040, vast areas, particularly in the Central Balkan Mountains, the northwest, and the Rhodope region, will lose even more inhabitants. On her maps, entire regions fade into lighter shades, marking shrinking populations. ‘The main problem in Bulgaria’s demographic space is polarization,’ she explains. ‘A few large cities concentrate people, jobs, and GDP, while entire regions are being left behind.’ In some areas, population density already resembles that of sparsely inhabited northern European wilderness zones rather than functioning rural communities. The result is a structural shortage of jobs and an erosion of public services, making long-term settlement increasingly unrealistic.

Drivers of decline

From the government’s perspective, depopulation is driven by three intertwined forces: low birth rates, high mortality, and long-term emigration. Minister of Labour and Social Policy Borislav Gutsanov describes the situation as urgent but not hopeless. ‘Demographic trends are extremely difficult to reverse,’ he says, ‘but if the right policies are implemented now, tangible results can be expected in twenty to thirty years.’ His priority, he argues, is to prevent the decline from entering what he calls a critical phase.

Despite these structural explanations, emigration remains one of the most decisive drivers of decline. After the fall of communism, economic instability, low wages, unemployment, and weak public services pushed Bulgarians to seek security elsewhere in Europe. As people leave, local economies weaken further.

But depopulation is not only driven by numbers or economic indicators. It is also deeply connected to trust, or the lack of it. Many Bulgarians did not leave purely in search of higher wages, but because they could not imagine building a stable and predictable future in their own country. Weak institutions, corruption, limited professional transparency, and the sense that rules are applied unevenly made emigration feel like the safest long-term choice. As Kazakov puts it: ‘People don’t leave only because of salaries. They leave because they don’t trust that the law applies equally to everyone.’

Lack of trust

That lack of trust is something Anita Dangova directly associates with her decision to leave, and with the hesitation many returnees still feel. ‘When you’re young, you don’t see a system that supports you,’ she says. ‘You don’t feel protected by the state.’ Corruption, in her view, is not an abstract political issue but something that shapes everyday decisions. ‘People hesitate to return because they don’t believe institutions will work for them,’ she explains. ‘Without trust in the system, even good job opportunities are often not enough to convince people to come back.’ Emptiness, in this sense, is not only demographic, it is institutional and emotional.

Despite this widespread distrust, Anita ultimately chose to return to Bulgaria. She is careful not to romanticise that decision. ‘There are still many problems and corruption hasn’t disappeared,’ she says. ‘But the country has changed.’ Compared to a few years ago, she sees more professional opportunities and a labour market that is slowly opening up, particularly in larger cities. Emotional attachment played an equally important role. ‘I missed my country. I missed being home.’

During the interview, she gestures toward the street outside. That evening, protests are planned in Sofia. ‘If we want to move forward, we need a different government,’ she says. ‘One that works for the people, not for itself.’

Political Change and Renewed Expectations

The protest Anita refers to had immediate political consequences. The following morning, the cabinet announced its resignation. For her, the moment symbolized possibility rather than certainty. ‘If we get new elections, we can choose a party we believe actually represents us,’ she says. ‘That creates hope, not just for people who stayed, but also for Bulgarians abroad who are considering coming back.’

Against this backdrop the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy has placed demographic policy at the centre of its agenda, combining measures to encourage higher birth rates and initiatives aimed at bringing Bulgarians abroad back home. From 2025 onwards, childcare allowances during the second year of maternity will rise from 780 to 900 leva after three years of stagnation, while women who return to work during that period will receive 75 percent of their salary instead of 50 percent.

At the same time, return migration has become a key pillar of the strategy. In the past five years, around 124,000 Bulgarians have returned after living and working abroad. Through the program ‘I Choose Bulgaria’, the government offers assistance with job placement, relocation costs, partial housing support, and language courses for family members, provided returnees secure an employment contract of at least six months. New measures are now being prepared to address internal migration as well, encouraging movement from large cities to smaller towns and supporting entrepreneurs willing to invest in Northern Bulgaria, the country’s most depopulated region. ‘Return migration is not just about bringing people back,’ minister Borislav Gutsanov says. ‘It’s also about where they can realistically build a life.’

This policy approach overlaps with the work of Bulgaria Wants You, a privately funded organization that actively targets Bulgarians abroad. Valeria Djukic the organization’s COO, emphasizes that migration decisions are largely rational. ‘Most people didn’t leave because they couldn’t see an future for themselves here.’ Yet she also observes a contrast between departure and return. ‘People leave for rational reasons, jobs and stability, but they return for emotional ones. They miss home. They don’t want their children to grow up without speaking Bulgarian or knowing their grandparents.’

Return reality

Anita belongs to this group of returnees, though her decision was neither sudden not purely emotional. After studying in the UK and completing a masters degree in the Netherlands and working a few years abroad, she and her partner returned to Bulgaria in their mid-twenties. ‘It was a long proces. We talked about it for months.’ Family ties, quality of life and a believe that the labour market was slowly changing all played a role. ‘But in the end, I missed my country the most. The quality of life was maybe better abroad, but when you start missing home, you start looking at more than just that. I came home with the believe that the country is improving. In that hope I came back.’

Despite the efforts of the government the gap between policy ambition and everyday reality remains, especially outside major cities. Villages with our doctors, kindergartens or reliable transport struggle to retain residents, let alone attract newcomers. Even when jobs exist, the absence of basic services makes long-term settlement unlikely. Valeria confirms this imbalance. ‘Most people who return settle in Sofia or other large cities,” she says. “Many would like to go back to their hometowns, but there are simply no matching jobs there.’

‘Its not believable to breath new life into Bulgaria’

For demographers Ilieva and Kazakov, however, expectations of large-scale rural revival remain limited. ‘As scientists, we believe in numbers and facts,’ Ilieva says. ‘And the numbers tell us it’s impossible to reverse this trend in the short term.’ An aging population, persistently high mortality, and a shrinking base of women of childbearing age mean that even if emigration slowed significantly, natural population decline would continue. Kazakov adds: ‘It’s not that we don’t want to believe in the future of this country, but based on the numbers, facts and projections we currently have its not believable that Bulgaria will be able to breath new life into its land.’

Minister Gutsanov does not dispute that reality. His focus, he says, is long-term consistency. ‘Demographic policy cannot depend on which government is in power,’ he argues. ‘Without continuity, no positive change can be expected.’ He has raised the issue at EU level, stressing that Bulgaria’s demographic crisis is part of a broader European challenge that requires coordinated action.

Between Return and Reality

The evidence suggests that return migration alone cannot halt Bulgaria’s demographic decline. Even if overall depopulation slows, breathing new life into rural areas remains extremely difficult. Most returnees settle in major cities, where jobs and services are concentrated, leaving small villages increasingly isolated.

Bulgaria is not empty yet, but it is thinning out. Whether the country can transform return migration from a hopeful exception into a lasting demographic force depends less on slogans than on structural change. For people like Anita, the decision to return was both personal and political. ‘Sometimes I still wonder what would have happened if I had stayed abroad,’ she says. ‘But at the end of the day, I’m happy I’m here.’ The conditions shaping that choice, however, remain unmistakably political.