For just over 50 years, the island of Cyprus has been divided in a Turkish and Greek side. There have always been Cypriots on both sides opposed to this, but unity has never seemed further away according to experts. Despite this pessimism, a small group of people and organisations are still aiming for peace and unity.

The issue

Cyprus has been a divided island for over 50 years, with the Turkish Cypriots having proclaimed their own, mostly unrecognised, state. In October of 2025, Tufan Erhürman was elected by the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus. Erhürman has been described as a progressive politician who supports a reunification of the island, unlike his predecessor. However, experts and organisations in Cyprus are pessimistic about a possible reunification of the island.

To understand the current situation in Cyprus, it’s necessary to know how the island got here in the first place:

Where do we stand now?

Right now, the situation is far from hopeful for the peace activists. According to Hubert Faustmann, professor of modern Cypriot history at the University of Nicosia, peace activism has ‘never been in a worse situation than it is right now.’ Currently it has been 8 years since the last peace talks, and no new negotiations have been planned.

The new Northern Cypriot president, Tufan Erhürman, is more open to opening peace talks than his predecessor, Ersin Tatar. However, this does not mean the talks will be successful. Erhürman has certain demands he sees as necessary for reunification, but experts say these demands would be very hard for the Greek Cypriots to swallow. On the other hand, for Turkish Cypriots these demands are the bare minimum. Keeping both sides happy seems like a paradox, but is necessary for unity, as both sides need to approve any plan with a referendum.

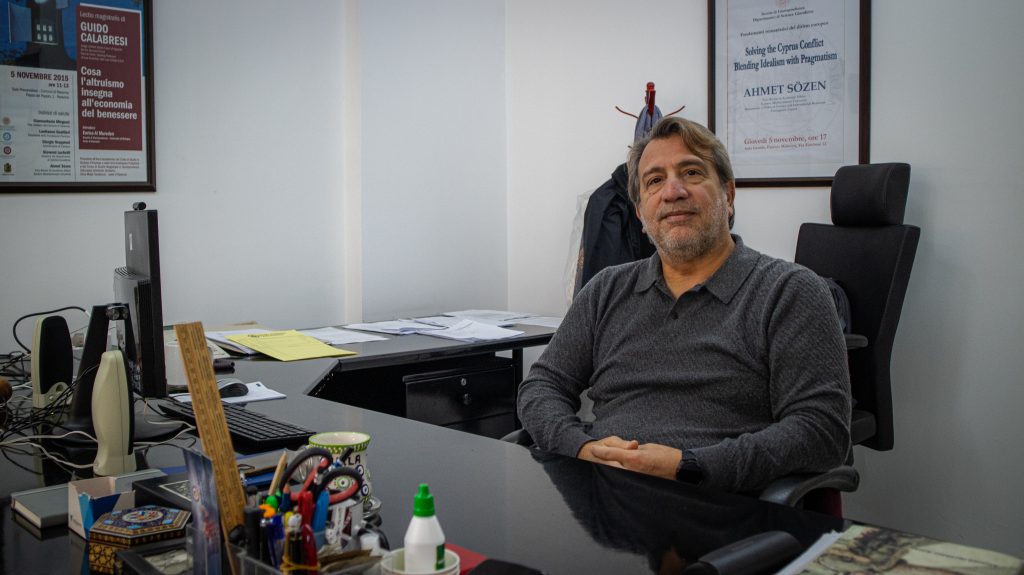

According to Professor Ahmet Sözen, even if the island would be unified, the problems aren’t gone. According to Sözen, the discord, caused by among other reasons a highly politicised education system on the island, would make keeping peace on the island difficult: ‘Even if there is a miracle and we solve the Cyprus problem and establish a federation, it might not live long, due to the lack of a cooperation culture in Cyprus.’

Civil Societies

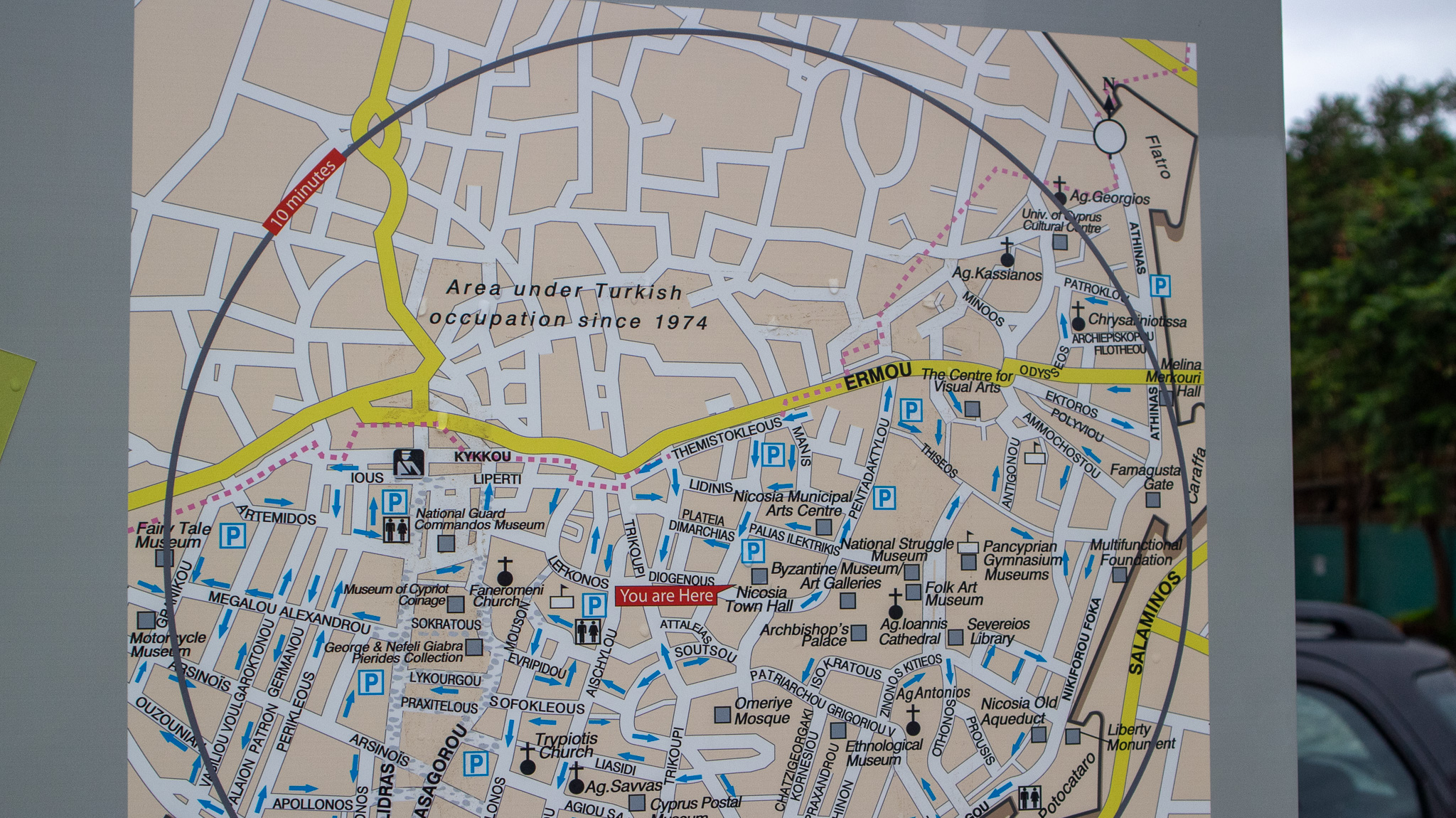

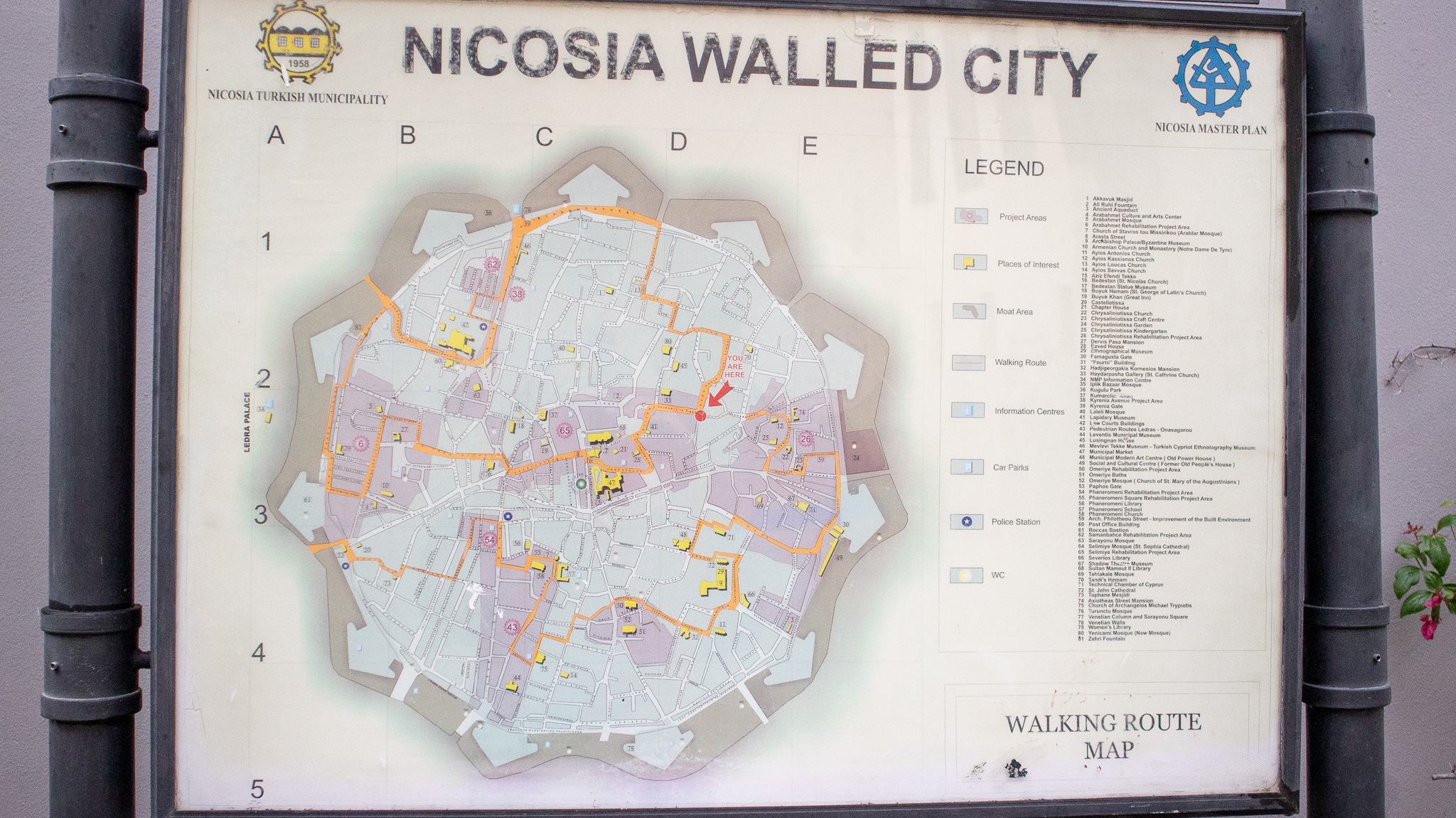

This cooperation culture needs to be built. Herein lies an important role for civil societies in Cyprus. A lot of these societies share a building, in a symbolic place. Inside the United Nations Buffer Zone in Nicosia, between the North and South, the Home for Cooperation is located, right across the Ledra Palace. The Ledra Palace is a former hotel that was the site of a vital battle during the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. The Home was set up by the Association for Historical Dialogue and Research, an inter-communal NGO working to unite Cyprus.

The Home is a community centre housing multiple organisations, like AHDR itself, the podcast platform Island Talks, and United Sports Cyprus. The centre also hosts a café, the Home Café, where unity-minded Cypriots from both sides, as well as UN-soldiers, come together to meet and drink coffee. To get to the building, one needs to cross one of the checkpoints on either side of the buffer zone.

Hayriye Rüzgar, communications officer at the Home for Cooperation, explains that the Home shares the pessimism with the experts: “We learned to not tie our motivation to politics. Things are always changing.’ Another reason for the detached feeling is the fact that the Home for Cooperation, together with other civil societies, is excluded from peace talks: ‘What is missing is the critical link between civil societies and the political negotiations table. There are a lot of things happening here, but none of this work is being translated into negotiation.’

Professor Sözen agrees: ‘The civil society is vital.’ However, he sees problems with the role of civil societies like the Home for Cooperation as well: “The activities of these peacebuilding societies usually take place in Nicosia, mostly in the buffer zone even, and mainly just among the ‘usual suspects'”.

At times, the governments’ actions towards civil societies go further than exclusion. In 2016, Imagine was launched. Imagine is an educational programme implemented by the AHDR, where students from all communities on the island get educated on discriminatory stereotypes and intolerance as well as get together at the Home for Cooperation to meet each other. The aim of this project is to bring the students together, to promote inter-communal unity and peace. In 2022, this project was suspended by the Turkish Cypriot community leaders, saying that it allegedly ‘undermines the existence of two states in Cyprus’, according to Turkish Cypriot newspaper Yeni Duzen.

AHDR faces difficulties from the Greek Cypriot community as well, according to their spokesperson. Starting in 2025, AHDR and the Imagine-program have faced attacks from right-wing politicians and media from the Republic of Cyprus. The AHDR organises study visits as part of Imagine, which right-wing groups view as illegal tours of the Turkish occupied territory. The spokesperson of AHDR emphasises that they are strictly an educational society.

Practical Issues

The split of the island is more than a political problem. It greatly affects the daily life of Cypriots. The most obvious problem is of course the hassle of reaching the other side of the island. Getting from one side to the other, requires crossing the UN Buffer Zone and getting past one of the few checkpoints scattered around the island. The rest of the Buffer Zone is a no-go zone, which is made very clear from signs and barbed wire.

The checkpoints look intimidating from the outside, flags of either Greece and Cyprus or Türkiye and North Cyprus. Crossing is far easier than it seems, however. Before the booth, there could be a small queue of tourists, Cypriots meeting their family or going shopping, or no one waiting. At the booth, one gives their passport or ID-card, it gets checked by an attendant who is often on their phone or talking with a colleague, they press a few keys on their keyboard, return the document and you can continue to the checkpoint on the other side of the buffer zone. This interaction takes 30 seconds at most, often without eye-contact or any conversation. For something that dominate the islands modern history and politics, the people working on it seem to care little.

For Cypriots themselves, this seemingly banal interaction can prove difficult. Turkish Cypriots need an EU-passport to cross, which is only given when both parents have the passport as well. Children from relationships with one Turkish non-Cypriot are ineligible to cross, which blocks off a large part of the island to them. Greek Cypriots have it easier on paper, but difficulties can still come up.

Varosha

Nafsika Hadjichristou is one of the Greek Cypriots who have had problems with the checkpoints. Her father is from Varosha, a ‘ghost town’ on the east coast of the island near the city of Famagusta. Varosha used to be one of the most popular tourist destinations for the jet-set in the early 1970’s, before the war. In 1974, the town was occupied by the Turkish army. It was closed to the public and remains abandoned to this day. In 2020, it was opened for visitors, which would give the Greek Cypriots who had to flee Varosha a chance to come back. However, this was in the middle of COVID-19-lockdowns, when all checkpoints were closed. This meant that Hadjichristou and her family could not visit her father’s birthplace, while tourists from Türkiye could.

After the checkpoints opened again, Hadjichristou and her family visited Varosha multiple times. One of these times, a family friend and filmmaker joined them. Despite it being illegal to record, she filmed the entrance while driving away in Hadjichristou’s family car. When she tried to cross to the north in Nicosia a few days later, she was arrested and brought to a military prison. After a long legal battle, she was released, but the Hadjichristou-family, including Nafsika who wasn’t present at the filming, were barred from entering North Cyprus for 1.5 years, once again blocking her and her father from visiting his hometown.

What Cyprus could be:

Intercommunal-minded Cypriots don’t only meet at formal meetings. One of the main meeting places is Hoi Polloi, a bar in North Nicosia, very close to the Ledra Crossing. This bar is frequented by Cypriots from both sides, often drinking and eating together. The main language is English. Hoi Polloi means more than just a bar for most of its visitors, which becomes clear on the bar’s 10th anniversary.

On the anniversary, a large crowd, mixed in every possible way, has gathered. People are dancing, sitting, alking, and walking around to meet everybody. To celebrate the big day, owner Simon Bahceli holds a speech in between his duties of serving drinks, summarizing the meaning of Hoi Polloi to Cypriots: ‘It doesn’t matter if you’re Greek, if you’re Turkish, no matter what your view is on the Cyprus problem, everybody is welcome at Hoi Polloi’.

Ali and Electra

Intercommunal contact can go further than friendship or meetings. Ali, a Turkish Cypriot, and Electra, a Greek Cypriot, have been together for quite a few years now. In 2022 Electra crossed to the North for the first time and met Ali there. In 2024, they moved to Pyla to be able to live together, both in their own communities. Pyla is the only Greek-Turkish mixed town on the island, located in the buffer zone between the cities of Larnaca and Famagusta, where Electra and Ali respectively worked when they moved. In Pyla, both Greek and Turkish Cypriots live together, which can be seen in the bilingual (sometimes trilingual) signs, a mix of Greek and Turkish flags, and heard on the streets.

Mixed couples are rare in Cyprus. Luckily, Ali and Electra didn’t receive a lot of disapproval from their families, but having a child-in-law from the ‘other side’ is a strange experience for the family. Ali recalls what his grandmother said to him after she met Electra: ‘Don’t make her sad, you are representing your whole nation.’ Electra’s mother and grandmother call Ali ‘Alexandros’ as a joke and before every visit ask if he’s bringing baklava. Despite this, Electra’s mother has never crossed to the north of the island, and never will, as the pain from the invasion remains for her. Most questions Ali and Electra get are how they will raise their children. (‘We can send them to an English school, but I hate the English’, Electra jokes)

Life in Pyla can be strange. Since it technically isn’t part of either side of the island, there is no police force except for the United Nations troops, getting a technical check for a car can be a mission that takes weeks and force you to appear before a court, and Turkish Cypriots don’t have to pay any money for electricity or water. The lawless situation is highly visible, with casinos and strip clubs lining the village streets. Despite this, Ali and Electra are happy to live in a place where they can both hear their language on the streets, where the Imam can be heard from the church.

Although the situation regarding a unified Cyprus is looking more pessimistic by the year, Cypriots in the north, south and middle navigate their ways through the complex political and personal landscapes. At least in Pyla, Ali and Electra have found a peaceful living situation, for now. As Electra says: ‘It’s a simulation of how Cyprus should be.’

All photographs in this article have been taken by Bram Wissink.