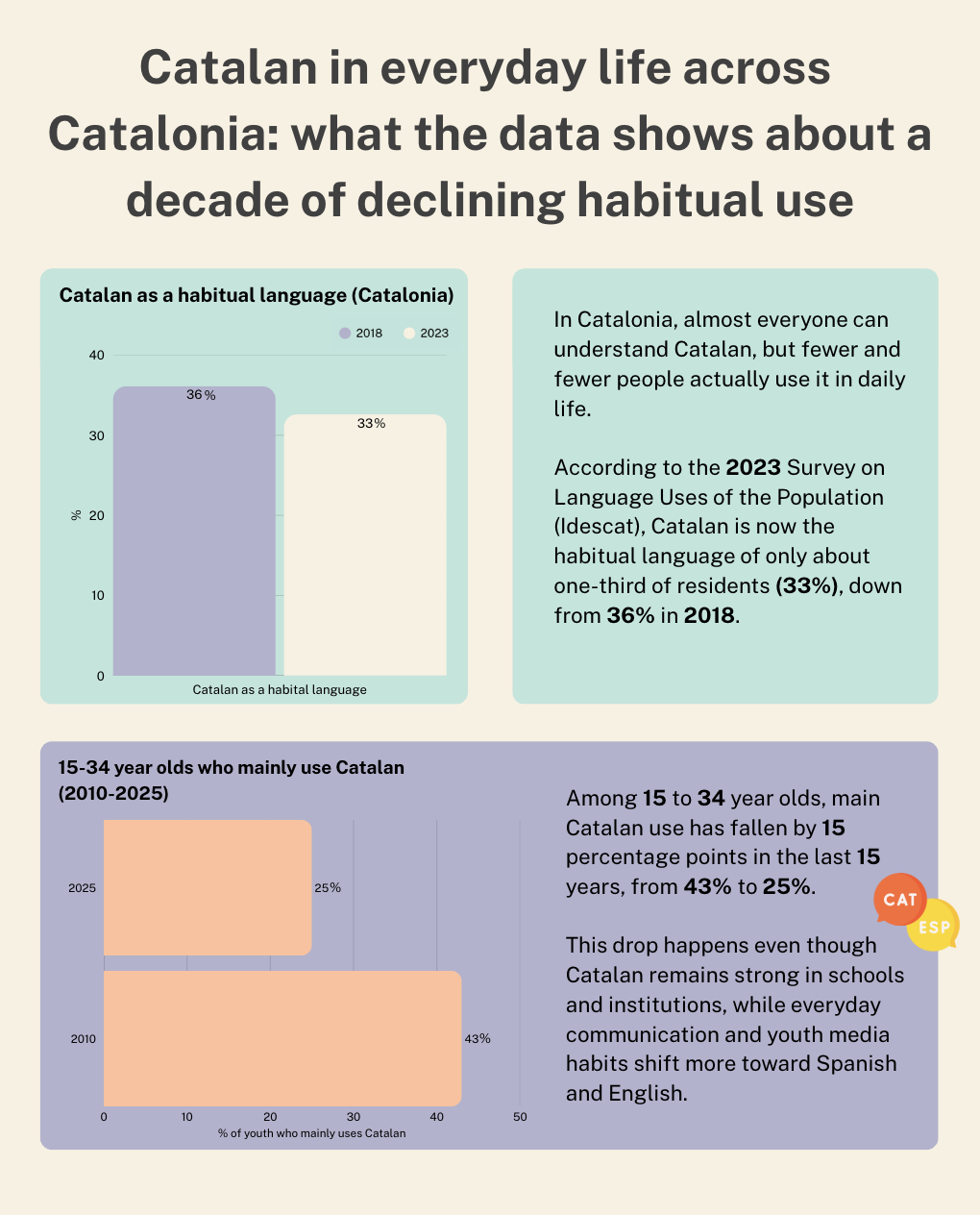

Less Catalan is being spoken in daily life across Catalonia, especially among younger people. The statistics clearly show a decline, prompting a question that often arises in conversation: if Catalan is still visible and protected, why does it feel less present in everyday usage?

Ivan Sevilla, a journalism student from Barcelona, puts it as follows: “When you walk in the streets, there are more people who speak Spanish than Catalan.” The shift, he suggests, is not only measurable. It is audible.

What’s the explanation for this sudden decline?

Inside schools, Catalan still sounds like the default. “All the subjects are done in Catalan,” says Gemma Martínez Hernández, a teacher with 27 years of experience at a secondary school in Terrassa near Barcelona. “Everything is in Catalan.” Spanish, she adds, “is just a subject.”

So why is Catalan fading outside of the classroom?

“There’s a big part of the population that does not speak Catalan at home,” Gemma says, because their families are “from other parts of Spain or maybe abroad.” Over time, she adds, “every time there are more immigrants from abroad,” and many arrive solely speaking Spanish, not Catalan.

In Barcelona, that demographic reality turns into a daily habit. “With my family… sometimes in Catalan,” Ivan says. “With my friends… depends on the location… Catalan or Spanish.” He repeats the same idea in a simpler form too: “It depends.”

Marcel Camacho, from Sant Andreu in Barcelona, starts with Catalan automatically. “It’s my first language,” he says. “Catalan was always the main one for me. Even now, I usually speak Catalan every day, with my family, friends, and when I meet new people; it comes naturally. It’s my default language.”

But when the group becomes mixed, he also sees why Spanish wins. In Barcelona, he says, “it’s easier for people who come from another country to speak Spanish than to learn Catalan, which can be a little bit more difficult.”

Gemma describes how Spanish becomes the safest option in places where strangers meet. People know customers will come “from outside and won’t speak Catalan,” she says, so they are “prepared to speak in Spanish.” It starts as “an alternative.” Then it becomes routine.

“If the customer is used to talking in Spanish, then in your business, you’re going to speak in Spanish also,” she says, “even if the paper you’re going to sign is in Catalan.”

That is why Catalan can stay official but lose conversational space.

And it is not only about migration. It is also about confidence. “For presentations… I prefer Spanish,” Ivan says. Spanish, he explains, “feels better for technical words,” and in public he can “explain better than Catalan.” Catalan is not impossible, he says, but Spanish feels smoother when he has to perform.

How do Catalans feel about the decline?

For Marcel, Catalan is not just a tool. “It’s part of my identity,” he says. “Something that makes me feel connected to my roots.” He describes feeling “proud” of it and proud of the culture attached to it. “I love it,” he says, talking about Catalonia, “the language, the food… I love.”

- Catalonia, Girona – Food Festival

- Catalonia, Girona

- Barcelona – People dancing during a street perfomance

When asked how he feels about the language being used less, he does not pretend it is neutral. “It is very sad,” he says, “because it’s a language that I love too much.” And yet his sadness sits beside realism. “I have to understand,” he adds, “that there are a lot of people, and it’s very difficult for all the people to speak Catalan.”

Ivan’s feelings sound different, but they are not empty. He says it is “strange” to see the decline, but he also calls it “normal for society,” shaped by “immigrants and politics.” Still, he says, “I would love to speak Catalan with my friends, because when you speak Catalan, the meaning can feel different, the love words, or something like that.”

Gemma does not speak in emotional language as much as the two students do, but her framing carries its own warning. Spanish, she says, is “prepared” everywhere because so many people arrive without Catalan. Catalan becomes “an alternative,” and in public facing life, alternatives can slowly become second choices.

Politics sits underneath the language usage, too.

Marcel describes independence as identity. “I don’t feel Spanish,” he says. “I only feel Catalan.” Asked if he wants Catalonia to become independent, he answers immediately: “Yeah. It’s my dream. One day… we can do it and be a country.” But he also sounds resigned about control. “We cannot do enough, it’s not in our hands.”

Ivan does not share that dream. Asked if he wants independence, he says: “No. For me, 2017 was a breaking moment.” In 2017, Catalonia tried to hold a vote on independence from Spain, and it triggered a major political crisis. He criticises how quickly things moved, and how leaders left. “It’s not good to go out to another country to live,” he says, because it becomes “not very credible.”

Even outside politics, both describe feeling judged elsewhere. Ivan remembers travelling to Madrid. “When you speak Catalan, people look at you with a strange face.” Marcel says similar things about other parts of Spain, where people have “treated me badly… just because I am Catalan and I speak Catalan.”

What does the future hold for the Catalan language and identity?

Gemma’s view of the future is not that Catalan disappears from public life. She points to support through culture and media. Catalan is promoted through celebrations and traditions, she says, and there is “a full radio station” and a “TV channel” connected to the Catalan government. “Catalan cinema also has subsidies,” she adds, including for films translated into Catalan.

But the forces pushing daily speech toward Spanish are still there. “With my friends, it depends,” Ivan says again, and that may be the most honest forecast. Barcelona remains mixed, and Spanish remains the lingua franca. In formal settings, Ivan still reaches for Spanish: “At university for presentations… I prefer Spanish.”

Marcel’s concerns are more subtle. Catalan is his “default language,” but he sees how easily the city pushes people toward Spanish. He wants a future where Catalan stays more than a symbol. “This is what we have to change,” he says, speaking about newcomers who arrive thinking “only Spanish.” People need to know that Catalan “exists,” he says, and that “the language is nice too.”

The near future, then, may not look like a disappearance. It may look like more code switching. More “it depends.” More situations where Catalan stays strong in school and official life, but Spanish keeps expanding in mixed groups and public ease.

And the shift will keep happening the same way it happens now: not as a single dramatic decision, but as thousands of small choices about what feels easiest to say first.