May 5 is the day of protest in Germany for the equality of people with disabilities. A good time to have a look at the situation of inclusion in general and what an inclusive city is. Especially with regard to the capital, because Berlin is considered a pioneer in terms of inclusion.

For an inclusive city and community, it is important that planning an inclusive city is participatory, involving all actors, and that there is a learning process from which improvements emerge, says Prof. Dr. habil. Michael May, head of the social space development at the University Rhein-Main.

Prof. Dr. Johannes Schädler from the Centre for Planning and Evaluation of Social Services at the University of Siegen says that when it comes to planning, it is mostly the obvious areas that come to mind when thinking about inclusion. “Housing and getting by in everyday life are something very basic, as is health care, and sport and culture then tend to take a background role because those are already higher needs.” But these should not be neglected either. Because the goal must be that everyone can fully participate in public life and is not hindered by society.

Therefore, says Prof. Dr. Schädler, agenda-setting is crucial when it comes to inclusion. Right at the beginning of political processes and decisions, it is necessary to analyse what the starting position is and what issues should be prioritized. Before a parliament deals with such decisions, there must first be a coalition of those willing to change that puts these issues on the agenda. It has been shown that “the municipal level is actually the decisive level when it comes to creating concrete conditions for inclusion”, says Prof. Dr. Schädler.

Thanks to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of 2009 there has been a change in awareness and an initiative for improvement. However, this applies mainly to cities, such as Berlin. Although not enough is being done there either, the situation in rural areas is often much worse. Furthermore, it can be said that more is done for inclusion in richer, educated middle-class neighbourhoods than in deprived neighbourhoods. This is a paradox in Berlin, but also in other cities because in deprived neighbourhoods housing is cheaper than in rich ones, but the situation for people with disabilities is worse and the financial means for change are lacking.

People with disabilities also need to be more involved in planning and decision-making. Prof. Dr. habil. May reports on a project that wanted to give severely mentally disabled people a voice. “We wanted to create space for them, they should say what their wishes are, how they want to live and what inclusion means to them”, he says. The workshop was a success and despite initial uncertainty, in the end, all participants proudly presented their results. However, such involvement hardly takes place in everyday political life.

Graf Fidi, alias Hans-Friedrich Baum, who has a disability himself, also sees the importance of the participation of people with disabilities. He has been involved with diversity, inclusion and accessibility since the beginning of his studies. The Berlin-based musician and activist also works as media educator at the social association “Lebenshilfe” in Berlin.

With his music, he is not only a spokesperson for people with disabilities but also triggers discussions and creates awareness, for example through panel discussions after his performances. He processes his own experiences in the lyrics and is aware of the responsibility that falls to him on this topic. “I have the feeling that I am doing something good, that I am making a difference, that I am needed”, he says.

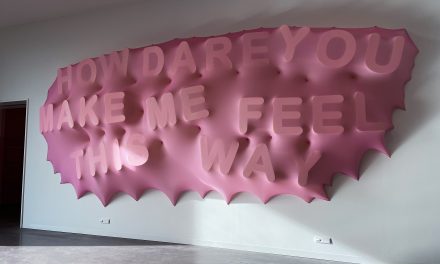

Graf Fidi says he does not feel restricted in any way in Berlin, but only because he can get up from his wheelchair for short distances, so he was able to avoid difficulties that are often encountered in public transport. Access to cultural activities for example has always been possible for him in Berlin. The city of Berlin and its cultural providers, such as the symphony orchestra, are very involved in this area. Among other things, there are special websites with information about museums and their accessibility. The State Ministry for Art and Culture and the city also initiate other projects such as “exceptions are the rule here” in Haus Bastian on the Museumsinsel. New approaches to inclusive education are being developed there. The project explores the question of what creative potential inclusive educational processes open up in cooperation between museums and educational institutions.

Although much more needs to be done, Graf Fidi also sees improvements in public transport in recent times. “It’s clear that it works better here in Berlin than in small towns, because it has to do with the fact that it is a conurbation and more people have to travel. That is why improvements happen faster”. He considers Berlin to be a city that is at the forefront when it comes to creating the best conditions for breaking down barriers and enabling inclusive housing. Nevertheless, “a lot still needs to change here and full inclusion in every area is still utopian.”