Strolling through the bustling streets of Lisbon, tourists and residents of the Portuguese capital are bombarded with street art left, right and center. With the traditional tile-covered façades, colorful painted walls and small works of art in lost corners, Lisbon is one massive open-air gallery. What many do not know is that several of these vibrant art projects are funded by the city council and others are illegal projects . Lisbon is the only European city that facilitates street art itself creating opportunities for artists, but not everyone in the street art scene is happy with this ‘imposition’ of the city council.

“The street art scene here is very rich. You can see a big variety in artists, and many styles”, Lisbon’s street artist James* explains. Lisbon has not always been such a colorful city. Until the 18th century the city consisted mostly of white buildings. After the earthquake of 1755, which destroyed large parts of the city, Lisbon started to incorporate color and tiles into the walls of rebuilt houses and pavements. This is still visible today. The emergence of the street art scene dates back to the democratic revolution of 1974. Inspired by revolutionary art in Maoist China and Castro’s Cuba, many Lisboetas covered the walls within the city with political murals and tags as a way of self-expression. This laid the foundation for the street art scene that exists today.

Illegal graffiti along the Escadas do Monte in the neighborhood Graça

Mural by Ozearv called ‘Tropical Fado in RGB Tones’ in the neighborhood Graça.

The Galeria de Arte Urbana

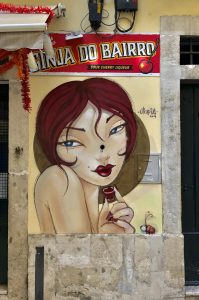

In 2008 there was another boost to the street art scene when the city council founded and funded the Galeria de Arte Urbana (GAU, The Urban Art Gallery). “The project was initially developed in the historical neighborhood of Bairro Alto”, Hugo Carados, coordinator of the GAU, starts to explain. The GAU was a natural next step after a cleaning operation across Bairro Alto, in which they removed the inscriptions that were vandalizing the facades of some buildings. Instead of simply removing all the illegal street art, they wanted to provide an alternative space where street artists were allowed to create their art in a legal and structured way. “The GAU initially started off as the curator for a set of street panels, opening calls for artists and writers to work on their visual transformation”, Carados says. These designated street art panels where a success and the GAU continued their work in other neighborhoods.

“The general aim of GAU is the promotion of artistic citizenship, recognising graffiti and street art as important expressions of contemporary culture, while simultaneously raising awareness and preventing vandal interventions”, thus Carados.

Véro, from street art collective YesYouCan.Spray thinks that GAU creates great opportunities for some artists in Lisbon: “I think it (GAU) made a big difference, especially to create a connection between artists, graffiti artists, street artists”.

Easy chatter, the rattling of spray cans beeing shook before use and the hiss of spraying paint can be heard on a warm afternoon at the Quartel de Santa Bárbara, a public space where communities get together. One of those communities is the YesYouCan.Spray street art collective. Today they are hosting an open graffiti workshop where curious and creative individuals can learn from already versed artists to create walls of art. One of these versed artists is James who for the last few years has left his mark on the street art scene in Lisbon and abroad.

Effects of the GAU on street artists

According to James, although the street art scene is very rich, big projects that are sponsored by the city of Lisbon or specific organizations are often assigned to the same individuals or passing artists: “It’s hard to get in. I don’t feel like it’s very embracing and inviting”, James says. To elaborate he mentions a project for a wall that he’s been working on and pitching to GAU: “I have the authorization of the building owner. All the neighbors and business owners got together to pay for everything. I’m not charging a penny for my labor, and yet I can’t get the permit”. Not only James sees this problem, but Véro points out the same issue: “The selection that takes place of artists who are selected or re-selected for big murals has little transparency, so a lot of graffiti artists feel ignored”. However, Véro is explaining that the GAU is trying to change this and work together with artists more.

“It is a shame that it is so hard to get authorization for a wall, because you have a city with plenty of walls, empty walls that are in good state and in good shape for a mural, that you don’t have to put any money towards to prep and there are lots of abandoned buildings that you could make into free walls, inviting artists to make them prettier than they are now”, thus James. According to Véro it is more difficult for an organization like the YesYouCan.Spray collaborative to get the same recognition and to be able to achieve things in neighborhoods as the GAU does. That’s why they mainly to focus on smaller walls that are less prominent.

When visiting Lisbon one can choose to join one of the many city’s walking tours. The Lisbon Street Art Tour, guided by Véro, is connected to the YesYouCan.Spray collaborative. Walking through different neighborhoods one will see many walls filled with art that are funded by the GAU as well as illegal murals. Véro also points out several spots where the GAU has painted over unauthorized murals and graffiti.

Minimalizing illegal street art

GAU does not only invest in creating new art projects throughout the city of Lisbon, but it also tries to safeguard the city’s rich heritage and prevent it from being vandalized. “We still have illegal graffiti, but the implementation of a free walls program will open more free spaces to be used as a canvas without curatorship’s or mediation, creating space for graffiti writers to work in legally authorized spots”, Cardoso explains. One of these spots where (graffiti) artists are allowed to paint is “Largo da Oliveirinha”. In this ‘free zone’ you can therefor find graffiti artists spray-painting in broad daylight. Véro acknowledges that to a certain level the GAU has had an impact on illegal street art in Lisbon, “…but not everybody wants to create something beautiful”. As much as the GAU tries to prevent illegal street art as possible, vandalism will never completely disappear.

Street artist James even thinks that GAU’s attempts to prevent illegal street art works counter active. Many unauthorized graffiti walls are removed by painting them completely white. According to James, this is not an effective way of dealing with illegal graffiti: “In this case, when you have like this type of mindset, all you’re doing is you’re presenting people with more blank canvases. It’s even more inviting.”

Other cities

The involvement of the city council in the street art scene has had a positive impact on Lisbon: “More and more artists are able to develop work in the public sphere and it has generated a dynamic in the city that today allows us to say that urban art is one of the watermarks of the city of Lisbon”, thus Carados. Whether funding for street art in other cities in Europe would have a positive impact on the neighborhoods is difficult to say. There are some cities where the city council is already looking into funding certain street art projects. But, as James explains, creating murals in a city like Lisbon is very doable, because there simply are a lot of empty walls. “I understand why it’s super difficult to get a wall in Manhattan. There are just not many walls”.

According to James, if other cities want to implement a similar street art department in their city, it is important not to make street artists in the city feel excluded and to keep in mind that the importance of street art is that is has to be accessible to everyone: “People like street art because they don’t have to go into galleries. It’s for people who might not be able to go to galleries and museums. If it’s not accessible to everyone, then what’s the point of street art?”. Even though artists in the Lisbon’s street art scene feel excluded and unheard, Lisbon’s approach has shown that with proper funding and by appointing designated areas for street art, graffiti can be turned into an asset to the city. An art form available to all.