Jan Sobottka in a Bucherbogen bookshop.

In these pictures me and Sobottka walk through one of the latest exhibition of Camera Work Berlin.

Together with an established photographer from a First World Country I interviewed a rising photographer from a developing region, the Georgian street photographer Nina Kunchulia. She considers Berlin as a location where photography plays a central role. Her photographic practice explores normal life activities by documenting market scenes along with public streets and arbitrary human events. “In Tbilisi, more people are starting to take photography seriously,” she says. The city shows great potential for photography yet the lack of connection to established photographers remains a significant barrier to visibility. A lot of it feels unfair.”

During her 2018 visit to Berlin she realized that photography stood at the forefront of the city’s cultural scene. Big art galleries during that period dedicated space exclusively to photographic art pieces. The situation with photography clashes differently in Georgia.

For her traditional art environments seem to preserve obsolete practices. Sculpture along with painting retains its status yet viewers consider these two arts forms outdated due to their repetitive nature. The same big names over and over. The modern sensation of photography appears as contemporary and present-day. Today’s people desire contemporary observation rather than historical perspectives which happened fifty years earlier.

The ability to engage with photography makes this medium a powerful tool. The practice of photography demands no expensive materials nor does it require formal training similar to the requirements of painting. “You just need a camera or even a phone and your own point of view,” Kunchulia says. Berlin provides the perfect environment for young people to express themselves through their photographs. It makes you feel seen.”

Together with an established photographer from a First World Country I interviewed a rising photographer from a developing region, the Georgian street photographer Nina Kunchulia. She considers Berlin as a location where photography plays a central role. Her photographic practice explores normal life activities by documenting market scenes along with public streets and arbitrary human events. “In Tbilisi, more people are starting to take photography seriously,” she says. The city shows great potential for photography yet the lack of connection to established photographers remains a significant barrier to visibility. A lot of it feels unfair.”

During her 2018 visit to Berlin she realized that photography stood at the forefront of the city’s cultural scene. Big art galleries during that period dedicated space exclusively to photographic art pieces. The situation with photography clashes differently in Georgia.

For her traditional art environments seem to preserve obsolete practices. Sculpture along with painting retains its status yet viewers consider these two arts forms outdated due to their repetitive nature. The same big names over and over. The modern sensation of photography appears as contemporary and present-day. Today’s people desire contemporary observation rather than historical perspectives which happened fifty years earlier.

The ability to engage with photography makes this medium a powerful tool. The practice of photography demands no expensive materials nor does it require formal training similar to the requirements of painting. “You just need a camera or even a phone and your own point of view,” Kunchulia says. Berlin provides the perfect environment for young people to express themselves through their photographs. It makes you feel seen.”

Exhibition of a Contemporary African Photography in C/O Berlin.

Still, Sobottka points out that while photography is being shown more often, it doesn’t always mean it’s valued economically. “People don’t buy photography like they do paintings,” he admits. “Galleries will show your work, but they’ll also say, ‘We won’t sell it.’ You do it because you love it.”

Yet the cultural impact of photography is clear. It documents the spirit of the times in ways that traditional art sometimes can’t. It can’t lie like paintings do. “Even during the Cold War, East Berlin photographers captured life in very intimate, emotional ways,” Sobottka says. “And you could feel the difference between the East and the West just by looking at their photos. That’s the power of photography, it’s never neutral.”

Kunchulia agrees. “Photography gives me a way to respond to what’s around me. It’s honest. And in Berlin, it feels like people actually care about it.”

By visiting German capital I could experience this significant evolution firsthand. I toured the expansive halls of C/O Berlin to see master and amateur photography spanning throughout each area. Several days into my visit to Fotografiska Berlin I had the chance to experience multimedia presentations of famous people’s portraits. The two institutions demonstrate distinct character while holding a common characteristic that Berliners are committing to photography exhibitions.

Still, Sobottka points out that while photography is being shown more often, it doesn’t always mean it’s valued economically. “People don’t buy photography like they do paintings,” he admits. “Galleries will show your work, but they’ll also say, ‘We won’t sell it.’ You do it because you love it.”

Yet the cultural impact of photography is clear. It documents the spirit of the times in ways that traditional art sometimes can’t. It can’t lie like paintings do. “Even during the Cold War, East Berlin photographers captured life in very intimate, emotional ways,” Sobottka says. “And you could feel the difference between the East and the West just by looking at their photos. That’s the power of photography, it’s never neutral.”

Kunchulia agrees. “Photography gives me a way to respond to what’s around me. It’s honest. And in Berlin, it feels like people actually care about it.”

By visiting German capital I could experience this significant evolution firsthand. I toured the expansive halls of C/O Berlin to see master and amateur photography spanning throughout each area. Several days into my visit to Fotografiska Berlin I had the chance to experience multimedia presentations of famous people’s portraits. The two institutions demonstrate distinct character while holding a common characteristic that Berliners are committing to photography exhibitions.

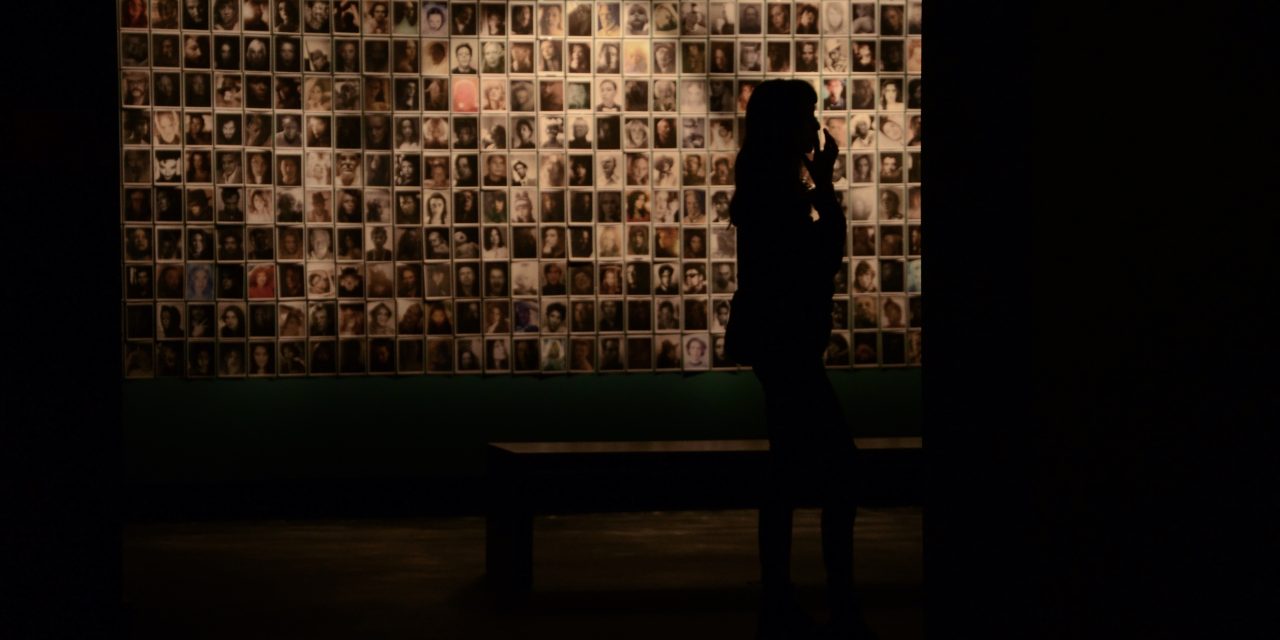

Multimedia photography exhibition in Fotografiska Berlin.

Berlin’s conversion toward photography can be described as poetry. This metropolis that previously separated itself with both physical barriers and political beliefs now exists because it welcomes diverse perspectives and the processes of image creation and historical preservation. As Jan Sobottka said: “Even ordinary photos, over time, become history.” Berlin serves as the canvas where living photographers create modern history through their photography activities.

Berlin’s conversion toward photography can be described as poetry. This metropolis that previously separated itself with both physical barriers and political beliefs now exists because it welcomes diverse perspectives and the processes of image creation and historical preservation. As Jan Sobottka said: “Even ordinary photos, over time, become history.” Berlin serves as the canvas where living photographers create modern history through their photography activities.