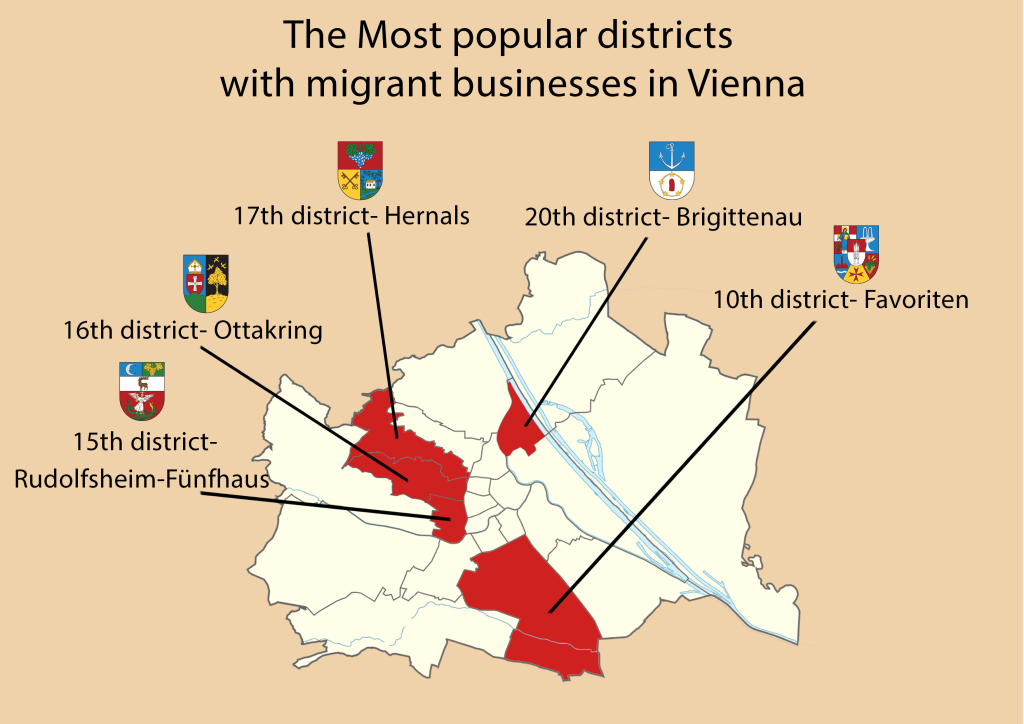

Vienna is a city full of culture. Throughout the decades many communities have found a home here, but the Balkan community is the one that stands out the most, not only in numbers but in flavors as well. Today, dishes like Ćevapi and Burek are easy to find across the capital, especially in districts like Ottakring, Rudolfsheim-Fünfhaus, and Brigittenau which have become real hot spots for Balkan cuisine in Vienna.

“There’s a saying in Austria – People come together through food.” says Ivana Cucujkic-Panic – an expert in inclusive marketing and communications and co-founder of Austria’s first diversity magazine. These restaurants are more than just places to eat, they help keep traditions alive, connect generations and bring culturally different people together.

Historical background

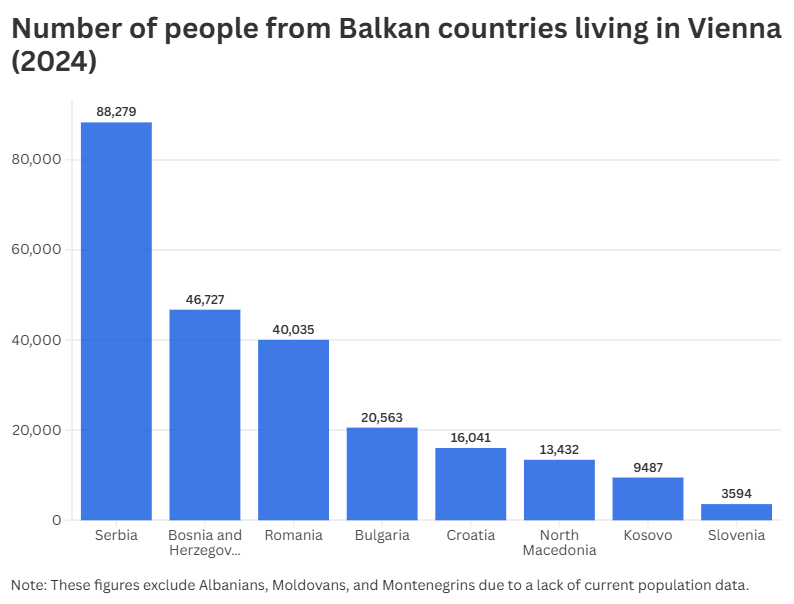

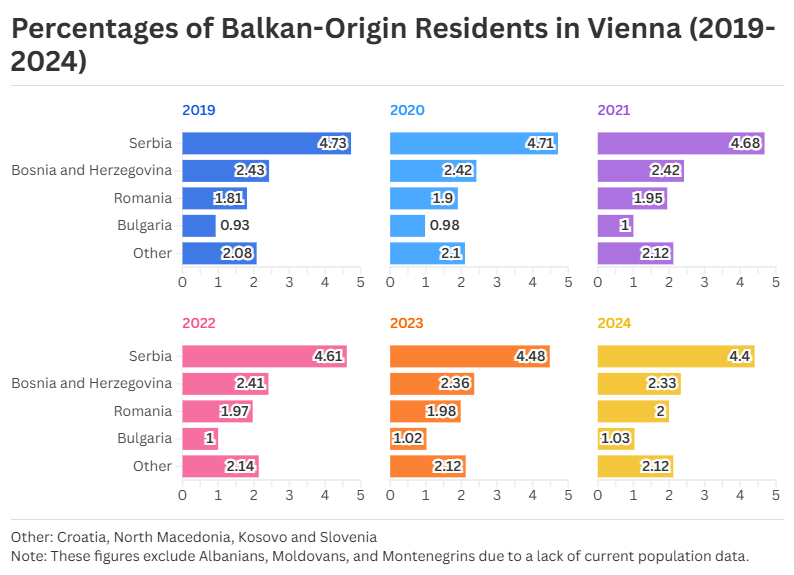

The emergence of Balkan culture in Austria is not fairly new. It began with the Gastarbeiter (Guest workers) programs from Yugoslavia in the late 1960-70s and continued throughout the Balkan wars a decade later (1980s-1990s). More than three quarters of all migrants of working-age currently living in Austria have arrived since the former event, with most entering between 1988 and 1995. As of 2024, the total number of people from Balkan countries living in Vienna is approximately 238,158, which is about 11.87% of Vienna’s total population (2,005,760 million).

As mentioned before, Ottakring district is one of the hotspots for Balkan cuisine. Known informally as the “Balkanmeile,” it is a central place where people from the Balkans live and run their businesses. Originally these people were low-skilled labor migrants or refugees, with poor German language knowledge. Because of these socio-economic circumstances self-employment was the only chance for social mobility for them and most of these small businesses run by migrants were in the food and hospitality sector which still is going strong till this day and is a big part of Viennese society.

Balkan Cuisine in Vienna’s Economy

It is no surprise that Balkan community has long been a driving force in Vienna’s economy. As Ivana explains, “The ex-Yugoslav population is one of the largest immigrant groups in Austria – especially in Vienna. Overall, so-called “ethnic economies” make up over 30 percent of Vienna’s economy. Gastronomy and food-related businesses are a key sector within that”. A study developed by Caritas Austria backs up her statement, Nationwide, 16% of Austria’s service and industry-sector workers are foreign nationals, and the service sector generates over 70% of GDP.

Although these numbers seem promising on paper, the bigger economic picture tells us otherwise. As Ivana points out, “The economic situation is a major challenge. Austria is currently the only country in Europe without economic growth. Several of the country’s largest traditional businesses have declared bankruptcy just this year.” The huge rise of prices has really affected the locals. Even Balkan food which has long been seen as the more affordable option when dining out could not withstand the wave of inflation. Seeing dishes that used to cost €8 priced at all the way to €20 is something that is hard to shake for the locals.

Food as a Cultural Bridge

Food is an active tool in social integrations, city branding, economic inclusion and cultural diplomacy. In places like Vienna gastronomy has become one of the main types of jobs for migrants. “migrant” food is seen as a positive marker of cultural difference, and therefore it is something that the migrants actively use to promote their cultural origin.

“Food in general has that power. But Balkan cuisine in particular is a melting pot of Central European flavors. It shares many culinary intersections with other cultures, which naturally fosters connection and cultural exchange,” says Ivana Cucujkic-Panic.

Balkan restaurant owners in Vienna often adapt familiar dishes like Ćevapi, Pljeskavica, or Burek to local tastes, sparking interest among Viennese diners. Over time, they learn how to showcase their cuisine in ways that appeal to a broader audience. For the Balkan community, this maintains a “taste of home” and for Austrian customers, it provides generous and affordable alternatives.

These restaurants have even shaped Vienna’s food identity. As Ivana mentioned in our interview dishes like the traditional Viennese dumpling (Knödel) share roots with Balkan and Central European cuisines. Food becomes a powerful way for migrants to connect with others, build their identity, and feel part of the community. In order to not be seen as the outsiders these communities are using their culture as a strength, showcasing it in a positive way and in a city shaped by migration, they remind us how culture can be both preserved and shared.