Soprano, Tenor, Culture: Arias in the air over the city Cluj-Napoca. The international spirit of opera is experiencing a nationalistic twist in Romania—but the divide is smaller than it seems.

Severin Weh

“La commedia è finita!” – “The comedy is finished!” The curtain drops and the audience rises, applauding and cheering the stars of the night. Opera singers in Cluj-Napoca perform either on the stage of the Hungarian State Opera or the Romanian State Opera. Both are significant cultural institutions in the city, staging major productions each year that attract locals, tourists, and culturally curious visitors alike. The second largest city in Romania is home to many various minorities from which the Hungarian one is the biggest; sometimes it can feel like Cluj has a personality disorder.

Cluj-Napoca, Kolozsvár, Klausenburg

The history of this city is written in many national hands. Today’s Cluj still bears the marks of its multi-ethnic past—in its architecture, its institutions, and its cultural life. The Austro-Hungarian monarchy, communist rule, and modern Romanian nationhood have all left their imprint on this city near the Hungarian border.

©All three by Severin Weh, Romanian State Opera

The Romanian State Opera building is a perfect example of this layered history. Built by Austrian architects in 1906, it was originally intended for the Hungarian State Opera. After the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the incorporation of Transylvania into Romania, the building was reassigned to house the Romanian ensemble. Step into the grand hall and it’s clear: this space was designed to impress. It smells like your grandparents’ old closet, and the chandeliers resemble the ones your grandmother might have had in her living room.

Today, the opera is bustling. More than twenty workers—tiny from afar like ants—are busy preparing the stage for a new production. “This year we’re celebrating over one hundred years of opera,” says Cristian Avram, deputy manager of the Romanian State Opera. The milestone marks not only a historical anniversary but also the continuation of a national cultural project that began shortly after 1918: asserting Romanian cultural presence in Transylvania through institutions like opera, theatre, and the university.

Two Operas, One City

The Romanian and Hungarian State Operas are just a few minutes apart, but to a sensitive ear, they can feel like different worlds. Yet this is often the nature of opera: sung in Italian, French, German, Romanian, or Hungarian—but never Romanian in the Hungarian Opera, and never Hungarian in the Romanian one.

To the uninitiated, this might seem like a cultural identity conflict. But it isn’t. As Avram explains, “We don’t see the Hungarian Opera as a competition.” Instead, the two institutions coexist peacefully, offering different repertoires and artistic visions. The Romanian Opera tends toward classical staging with modern technical elements—video projections, LED effects—while the Hungarian Opera often embraces more experimental productions. Both institutions collaborate occasionally, including joint concerts and Cluj’s Opera Aperta festival.

Cross-attendance exists, but unevenly. Romanian audiences are less likely to visit the Hungarian Opera, often due to misconceptions about language barriers. “People think Traviata is sung in Hungarian. It’s not. It’s just the subtitles,” Avram notes. Meanwhile, members of the Hungarian community regularly attend Romanian performances, drawn by internationally known productions and guest stars.

A City’s Cultural DNA

A look into the past offers nuance. Under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, nationalities lived side by side across a unified kingdom—now divided by national borders. A large German-speaking population once lived in Transylvania. After the empire fell, many left, though they had been well integrated. A small community still survives in rural areas, but as it ages, their unique dialect fades. One day, this region may be entirely Romanian.

Balázs Bodolai, an artist at the Hungarian State Opera, recalls his upbringing in Romania as part of the Hungarian minority. “It was normal for our community to stick together,” he says. “That’s different today, and never in the opera.”

©Severin Weh, Balázs Bodolai in the Hungarian State Opera

© Severin Weh, Honorary wall for famous Hungarian artists in the Hungarian State Opera

“Born This Way”

Lady Gaga? If we’re asking questions about identity, she’s as good a starting point as any. Opera, after all, is little more than long, high-pitched, old-school Lady Gaga songs. And like Gaga, identity is performance. It’s a story crafted by elites of a community to foster a sense of unity and belonging.

©Severin Weh, sculpture of a Hungarian artist in the Opera

So why is identity so often treated as static—trapped in the hands of the state or its political stewards? To control the cultural narrative is, in effect, to shape a community’s self-conception—an act of power that, at its highest level, is exercised by the state.

Which brings us back to why elites care so much about culture. They need to hold power to control the cultural narrative and they need to control the cultural narrative to hold power. Opera, as a high art, carries prestige and soft power. That Cluj-Napoca has two national opera houses—one Romanian, one Hungarian—says a great deal about the city.

Shifting Numbers

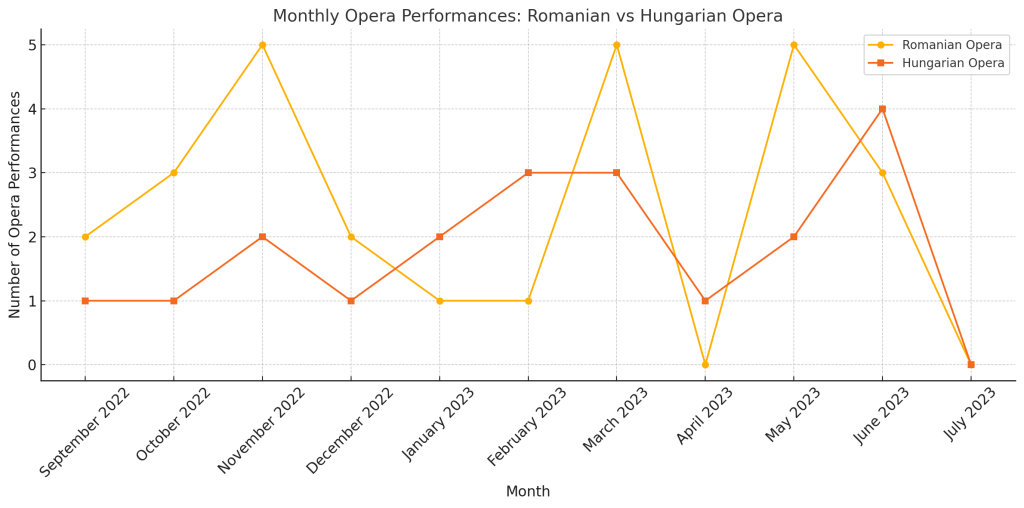

©Severin Weh and AI, Number of Opera performances throughout the theatre season 2022/23

If you look at performance frequency, the Romanian State Opera appears more established. It consistently stages more shows than its Hungarian counterpart. Census data from 2021 confirms a demographic shift: the Hungarian population in Cluj-Napoca is declining, currently around 11–13% of the city’s population. Still, this minority maintains a strong institutional presence—schools, newspapers, theaters, and, crucially, its own opera house.

Avram points out that audience diversity is also shaped by history and education. Generations of separation in schools have created parallel cultural tracks. “But the goal isn’t assimilation,” he says. “It’s coexistence. The presence of two national operas in one city is not division—it’s depth.”

A Stage for Dialogue

Opera is a space of emotional universality. Verdi, Puccini, Mozart—they don’t belong to any one nation. As Christian Avram puts it, “Opera can be a powerful bridge, precisely because it operates on an emotional and symbolic level.” It’s a chance to share stories and sorrows beyond linguistic boundaries.

Cluj-Napoca’s model is rare in Europe: two public opera houses in two languages, supported by the same ministry. Their continued cooperation, in festivals and infrastructure, points toward a cultural ecology based on mutual respect.

©Severin Weh, collage in the Hungarian State Opera with Loekie

“Oh, my homeland, never shall I see you again!”

One of the most heartbreaking arias in Aida, this line is sung in Act III as Aida mourns her lost homeland of Ethiopia. She stands torn between love and national loyalty. This year Aida is on the stage again to mark the opera’s 105th anniversary. The stage is heavy with sorrow—but in Cluj-Napoca, the audience looks up.

The aria is in Italian, but above the stage, the surtitles glow in Romanian. And this may be the most important lesson of all: culture isn’t about exclusion—it’s about understanding. Hungarian and Romanian audiences sit side by side when the curtain falls. Opera lovers go to both venues not because of surtitles, but because of the music.