The Amazonia exhibition was displayed in Brussels at a time when Europe is reassessing its environmental stance on a global scale. Beyond the political and legislative norms about climate change, the exhibition highlights an equally important and powerful message: an emotional force of art and its influence on societal narratives tied to action for improvement.

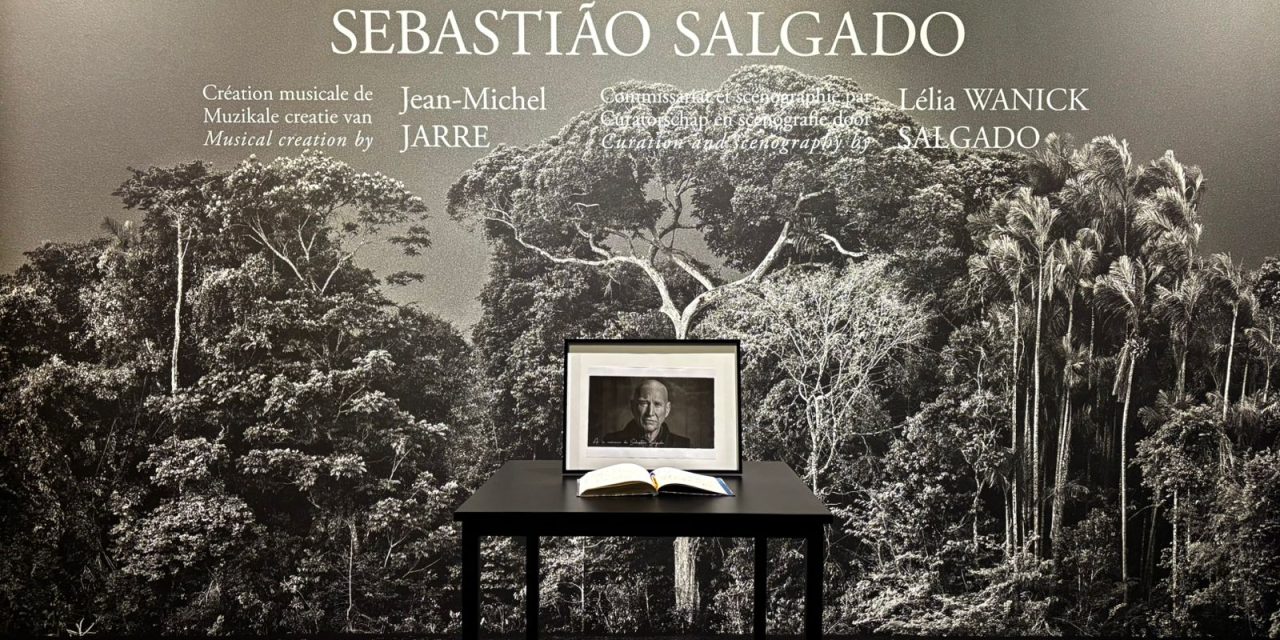

The immersive photographs of Sebastião Salgado, combined with large-scale visuals and soundscapes created by Jean-Michel Jarre, do more than document the rainforest; they form a sensory and emotional experience that can shift perspectives, challenge ideologies, and influence public discourse.

As Sandro Kelauridze, an Audio-Visual Arts expert, states, “Original visual creativity executed with a great sense of imagination and invention evokes emotions in viewers that are not accessible daily.” By unlocking new perspectives and emotions, art can reshape one’s interpretations of the world around them. shifting interpretations can influence values, alter opinions, and encourage individuals to take greater responsibility in making informed political choices.

This dynamic is especially relevant and meaningful for the European Union. The EU has put environmental protection at the core of its strategic decisions for strengthening the undeniable need for healthy cooperation between people and nature. Political projects such as the European Green Deal, the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030, or the regulations that prevent imports linked to deforestation act as a defensive and preservation mechanism for maintaining a livable planet. But still, policymakers increasingly recognize that scientific reports and policy briefs alone cannot mobilize public support; emotional engagement through photography, film, exhibitions, and immersive storytelling is just as essential.

Sandro articulates this link very clearly: “People are mostly motivated by emotions rather than cold logic. Art can disrupt existing emotional attachments and create new ones, which then lead to real action.” So, if art can shift emotional connections, it can shift public opinion, and public opinion influences political outcomes across the EU.

However, we can’t forget about the risks that political art can carry. Artistic work dealing with political themes must keep a delicate balance. If the message is too symbolic or abstract, audiences may feel it does not address the issue clearly. If it is too direct, it can drift towards propaganda. Sandro explains that creators must approach political themes with caution, because their work can lead to “real-world consequences.” This also applies to the dilemma that policymakers face: how to communicate urgency without oversimplifying, overwhelming, or manipulating.

Political art or ecologically oriented productions mainly circulate in narrow cultural circles, which may not reach broader audiences or people who are not interested in the topic to begin with. This is particularly true for cities such as Brussels, where exhibitions are often visited by policymakers, NGO workers, diplomats, and artists – influential audiences, indeed, but not representative of the wider European public. The impact of exhibitions with strong public-interest messages could be amplified through collaboration among cultural institutions, environmental NGOs, and EU bodies, ensuring these messages reach a larger, more diverse audience. In line with this approach, the Amazonia exhibition collaborated with Greenpeace, an international environmental organization that works to protect the environment and promote peace. Through workshops, public talks, and educational materials, visitors were not only exposed to Salgado’s striking images but also invited to take actionable steps and engage in policy discussions.

Visual art may not replace policy, but it can help make policy possible by changing emotional climates, challenging ingrained ideologies, and calling for empathy. In this sense, Amazônia is not only an exhibition about the rainforest; it’s part of Europe’s broader cultural and political negotiation of its environmental future.