On a chilly December morning, artists, curators, and cultural workers took to the streets of Berlin. Cardboard signs everywhere, choruses of chants, and unified people signified a city bleeding culture. On December 18, they protested once again, demanding that Berlin’s art scene be treated not as a luxury, but as a core part of the city’s identity.

For decades, Berlin has been known for its freedom, affordability, and openness to experimentation. Empty factories became studios, basements turned into galleries, and art spilled into the streets. But since 2024, major budget cuts have put this identity under pressure. Behind abstract numbers and parliamentary decisions lies a growing instability that is already reshaping Berlin’s artistic ecosystem.

With the outrage issue becomes clear: the biggest problem is not only the lack of money, but the uncertainty created by unpredictable political decisions. As funding becomes unreliable, the fragile structure that supports Berlin’s independent art scene begins to crack, putting the city’s cultural appeal at risk.

The infrastructure behind Berlin’s art scene

To understand the impact of the cuts, it helps to walk through Berlin’s neighbourhoods, such as former industrial buildings in Wedding, Kreuzberg, or Neukölln, many of which quietly house artist studios behind unmarked doors. Berlin has long supported artists not by funding individual artworks, but by subsidizing studio spaces, allowing art to be made in the first place.

This system emerged after reunification, when vacant buildings were gradually formalized into a publicly supported studio programme. Today, it includes over 1,000 studios and more than 100 studio apartments, while more than 3,000 artists remain on waiting lists.

According to Lennart Siebert, who has worked in cultural politics for over fifteen years and is now a studio commissioner in Berlin, studio space is essential. “Without a studio, there is no art,” he says.

What actually changed with budget cuts

Starting in 2024, funding decisions marked a clear turning point. Two key budget lines were sharply reduced: funding for new studios by 80%, and funding to maintain existing ones by 20%. The effect was immediate. No new studios would be developed, and even current spaces were no longer secure.

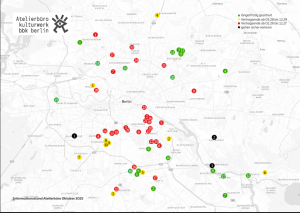

To visualize the risk, Siebert and his colleagues at BKK Berlin mapped all 68 studio buildings in the programme using a traffic-light system. More than one-third were marked red, meaning their contracts could expire between 2026 and 2027. Several buildings have already been lost, forcing nearly 50 artists to leave their workspaces. This loss is felt across the city. Siebert estimates that five to seven percent of artists have already left Berlin because of these changes. Others remain, but no longer create, having taken on different jobs to survive. This is happening despite Berlin having over 1.6 million square meters of vacant commercial space, empty rooms, while artists are pushed out.

Green – secured long-term; Yellow – contract ending between March 2028 and December 2029; Red – contract ending between February 2026 and December 2027; Black – will be lost for sure

Insecurity is the real crisis

The damage goes beyond physical spaces. Janina Benduski, an arts community organizer, describes a climate of constant uncertainty. “Even when funding still exists on paper, people don’t know if it will be there next year,” she explains. This makes planning exhibitions, collaborations, or long-term projects almost impossible.

Freelance artists are the first to feel the impact, followed by small institutions and, eventually, audiences. Fewer exhibitions open, fewer performances premiere, and cultural life quietly shrinks.

Julia Glesner, Professor of Culture and Management, adds that the real danger lies in the long term. Cultural structures can be dismantled within a year or two, she says, but rebuilding them takes much longer. Independent spaces are especially vulnerable because they rely on public funding and trust-based networks. Often, the cuts do not just cancel projects; they prevent future ones from ever being imagined.

Together, these developments threaten more than individual careers. They risk turning Berlin’s culture into something more exclusive, dominated by large institutions and wealthier audiences. What is at stake is not culture itself, but the openness and experimentation that once defined it.

Resistance and solidarity

However, if there is one opposing force to the budget cuts, it has to be collective resistance. The decision to implement budget cuts was unexpected. However, the outcome was an even more unexpected show of collective resistance among artists and institutions across different fields.

The protest movement has a decentralised structure. Differing sectors are responsible for the activity, whether it be a protest or a concert, and there are weekly meetings for organising purposes. The result of this was the “Save Our Studios” petition, which gained more than 7,000 signatures and was submitted to the cultural leaders in Berlin. The impact of the demonstrations is clear. Some cuts were mitigated, the political communication succeeded to some extent, and cultural policy became a topic of public interest before the elections. Research confirms that 80 to 90% of Berlin’s population is in favor of cultural funding.

Perhaps most surprisingly, it has engendered solidarity across deep-seated divisions. As Benduski notes, opera houses and small neighbourhood libraries are now standing side by side. “That has never happened before,” she says.