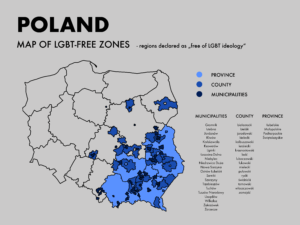

In July 2020 Polish citizens re-elected their president Andrzej Duda, who used heavy anti-LGBT rhetoric in his campaign. One-third of Poland has been declared an ‘LGBT-free zone’. According to ILGA-Europe, a non-governmental umbrella organisation advocating for human rights and equality for LGBT people, it is now the most homophobic country in the European Union. Bart Staszewski, a 30-year-old gay activist and author of the photo project ‘Zones’, talks about how the policy affects the LGBT-community and what the rest of the world can do to help.

What impact does Andrzej Duda’s presidency have on the everyday life of LGBT-people?

“The liberal government before Duda didn’t treat us like an important subject but we were not a target. The whole atmosphere has changed dramatically since Duda first became president in 2015. There was one huge case, where a printer refused to print posters for an LGBT-organization. The government was on his side. The big anti-LGBT propaganda started in 2019, which I describe as the worst year for the LGBT-community. When you are the target of such propaganda on a daily basis you feel threatened, you feel like a second-class citizen. Before the European Parliament Elections there were daily broadcasts on public TV describing us as some Western ideology worse than communism.”

How does Polish society treat LGBT-people?

“I would never hold the hand of my boyfriend in public. It only happens during Pride Parades, where we have police to protect us. Before Duda was elected I was able to put a rainbow flag on my balcony. Now I am too scared because people would throw stones onto my balcony. 70% of LGBT-teenagers show symptoms of depression and nearly half of them have suicidal thoughts. I’m privileged to live in the capital city, to be accepted by my parents. I have it better than those who live in ‘LGBT-free zones’.”

What does it mean to live in an ‘LGBT-free zone’?

“It depends on how conscious you are of politics. One girl said she didn’t experience any homophobia. I then asked her, if she could go to school parties with her girlfriend. Her teacher had told her it was impossible. There are no police officers who go around looking out for LGBT-people, but such a symbolic law creates a chilling-effect. Schools are highly dependent on the city budget.”

Why is the Law and Justice Party so popular in Poland at the moment?

“They give back dignity to those who live under poor conditions. In the 1990s, when the democratic system was introduced, many people were suddenly abandoned by the country. With the ‘500+’ welfare package they can finally go on holiday again. On the other hand, public television is a very influential tool in the hands of the government. The propaganda is worse than in the communist era. They create fake news, but when you live in smaller cities and you don’t have any other TV programs, you believe them. At the Bialystok Equality March, which was the most violent Pride Parade I have ever seen, there was a hooligan asking the police officers: “Why are you protecting those ‘faggots’? They want to teach four-year-olds to masturbate.” This was part of the Law and Justice propaganda.”

With many protests going on right before the election many LGBT-people seemed full of hope regarding their future. What has changed since Duda was re-elected in July?

“Despite recent events the community is becoming stronger. Last year we had the highest number of Pride Parades in Poland. It is in our Polish DNA to create an opposition every time the government oppresses us. We don’t hide in the closet. When Margot was arrested in August, I could see young people on Instagram taking part in solidarity protests in every corner of Poland and in the rest of the world, in Trondheim, in Washington, in Berlin. Many don’t want to spend their whole life fighting for their rights. Everyone from the LGBT-community knows at least one or two people who are preparing to leave Poland very soon, others have already left.”

What can people from around the world do to support you?

“Create pressure by gathering in front of Polish embassies. Send letters to the twin cities of ‘LGBT-free zones’. Funding is also very important. Only 10% of the activists are paid for their work. Of course, we can’t replace the state where it is not working. I don’t believe in the idea that we are able to change Poland with the help of just a few NGOs. Politicians from countries with secured LGBT-rights also need to put pressure on the Polish politicians when they meet them by asking them one simple question: ‘What is the situation for LGBT-people in your country?’ Usually the answer is that there is no violence because they don’t measure it. When there is someone beaten up in front of a gay club, police officers don’t mention the homophobic background in their report.”

Article 21 of the Fundamental Rights of the European Union also states that “any discrimination based on any ground such as […] sexual orientation shall be prohibited.”

“At the end of last year, the European Parliament voted in favour of condemning the ‘LGBT-free zones’ but nothing happened. In July a couple of cities lost EU-funding, but they were small funds, about 25,000 euros. The Minister of Justice told them not to feel pressured into changing their view. He gave them 250,000 zlotys. When Poland joined the European Union, it agreed on some values that should be shared by all member countries. The EU must react more strongly. Hopefully a directive will be introduced very soon which prohibits homophobia on Polish media with big penalties behind it. When the house of your neighbour is burning you don’t just watch and create a statement for the press or the TV, you help those who are inside the house.”