While the struggle for the survival of minority languages endangers Europe’s linguistic diversity, the EU’s commitment to multilingualism seems more unclear than ever, exemplified by Spain’s rejected attempt to elevate its co-official languages to official EU languages.

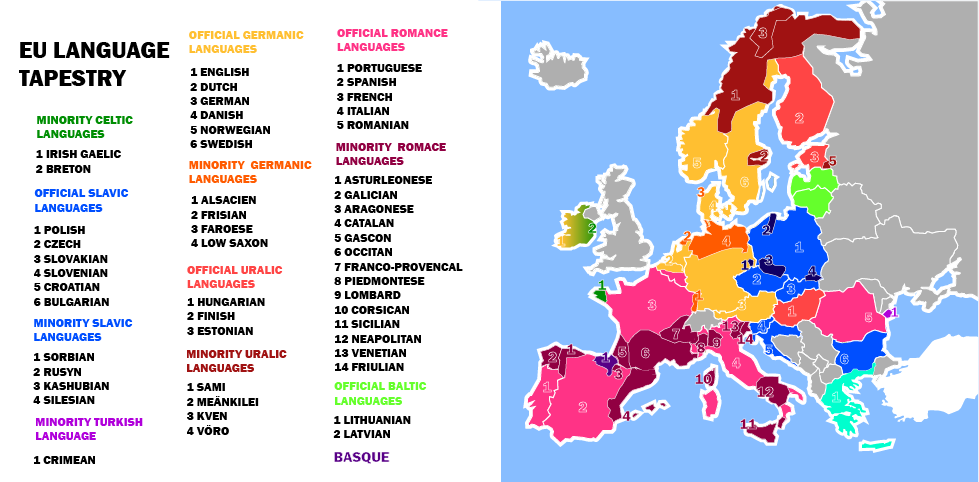

Minority languages like Basque, Catalan, Frisian, Breton, Irish or Sami are those spoken by a smaller percentage of the population and they are associated with specific cultural or ethnic communities. The status of these languages vary significantly with some having official recognition in specific regions, granting them certain rights in education or media (like Galician), while others may lack any formal acknowledgment (like Breton) and with the only language having official status in a national and EU level being Irish Gaelic. Dr Aurelie Jouber of Groningen university states that these disparities make “the fate of minority languages in Europe is very unequal”. The overall lack of recognition and legislative protection is a big problem that leads to the marginalization of these languages in education, media and therefore in public life and gets bigger due to the negative impact of the current globalization and the rise of the far right.

BASQUE AS A CASE STUDY

Basque, also known as Euskera is one of Europe’s most unique minority languages in which the importance of legislation for its promotion is very clear. It is spoken in the Basque Country region located in small mountainous regions of northern Spain and southwestern France. Basque is an isolate with no known linguistic relatives and it’s considered by many to be the oldest living language in Europe.

Euskera is not only uncommon because of its origins, its already mentioned legislation, is rooted in duality and it shares light on how important recognition is for the survival of these languages. The Southern Basque Country or Hegoalde, located within Spanish borders holds official status alongside Spanish in most areas recognized by the Statute of Autonomy and subsequent legislation. This acknowledgment extends to government, education, and public services, symbolizing a commitment to preserving Basque linguistic heritage. This commitment seems to be growing with new laws now permitting using basque language in the national parliament but some think that this is not enough, criticizing the secondary importance in basque in the constitution.

In the Northern Basque Country or Iparralde just across the border in France, the situation concerning the Basque language is critical as it lacks any official recognition. Eneko Bidegain writer, teacher and advocate for basque’s rights explains France’s rejection by pointing out how “France’s history in the language matter it’s long and linked with France’s nation creation.” He explains that until the XIX century French barely dominated half of the country. However, after the revolution, a transformative shift occurred and when facing the challenge of rebuilding the French nation they thought that there was a need for a unified French nation with a common language and culture. Bidegain notes that France has “clung to this mindset”, even though they are no longer explicitly pushing for the eradication of regional languages. Instead, there is a reluctance to grant these languages rights beyond the confines of individual households. This mindset is specially pushed by parties like Renaissance and politicians like Marie Lepen and it can be seen in examples as them not letting Basque students take their exams in basque. Paris, as the centralized hub for the economy, media and culture, further reinforces this push for linguistic uniformity. Bidegain highlights this by stating, “France at the end of the day it’s a centralized country, one of the most centralized in the world. Everything is centralized economy, the media, culture… and the language is the thrust of that centralization”

This legislative duality creates a unique scenario where support from one country contributes to the language’s development in the territory of another, highlighting the important role of legislation in linguistic preservation. Bidegain emphasizes the impact of official status in South Spain, stating, “The officiality in south Spain its a guarantee that Basque will remain alive or that it won’t die as fast” Despite stating that the policies supporting the Basque language are not enough, Bidegain points out that they have yielded positive outcomes in the Northern Basque country. He suggests that thanks to the support of the southern region, Basque takes more daring initiatives compared to other French regional languages. This is proven right because while basque is among the last minority languages in France in terms of absolute numbers due to its small regional presence, the movement supporting Basque language stands as an exemplary model for minority languages together with Catalan which encounters a similar legislative situation.

Through this we can see that legislation plays an important role in shaping the destiny of minority languages. Knowing that the Spanish government tried to establish Basque as an official language within the EU but this request was turned down because countries like France or Sweden and most lately Belgium expressed their rejection to this idea. Bidegain states that “In my opinion recognition in Brussels would be pretty much symbolic. I think basque’s goal is to make basque the official and main language in all the basque territories” However, the prospect of officiality in the European Union introduces a potential contradiction particularly in France “officiality in the EU would create these contradictions in France because it would not accept a language that is recognized by Europe, and that contradiction would help to reach Basque’s main goals.” Though this prospect are hopeful, it is apparent that achieving official status in Europe remains a challenge even if Europe states to have a compromise with multilingualism.

EU AND MINORITY LANGUAGES

To fulfill its compromise with multilingualism the European Charter for Regional or Minority languages, established by the council of Europe, aims to safeguard and promote these languages. But as mentioned before, this commitment is faced with skepticism Dr Aurelie Jouber talks about how “the European Union in general is a bit of an ambiguous place in terms of its policies”. The EU’s commitment to multilingualism, while created with good intentions, often falls short, creating what Dr Aurelie Jouber describes as a “a paradox or contradiction between what they say they want to do and what they actually do” This becomes apparent in instances such as the discussions like those surrounding Brexit, where the role of English was debated or the already mentioned failed attempt by Spain to elevate its co-official languages to official status within EU.

One of the main challenges that the EU faces when trying to support linguistic diversity and regional languages is the power dynamics of member states. linguistic diversity in regions is hindered by the inherent power dynamics of member states. This debate regarding the states’ power in the EU is not new and it has always been relevant for regional cultures Eneko Bidegain mentions how “There was a time during the development of the EU when regional nationalist movements advocated for a Europe of the peoples rather than a Europe of the states. However, in the end, Europe did not replace the states, and the states continue to be stronger than the Union itself” This power dynamics of the member states greatly affect regional languages since countries like France will never accept minority languages.

THE IMPORTANCE OF MINORITY LANGUAGES

The rejection of regional or minority languages by these states and people that do not partake in these cultures comes from a belief that for a country to be strong and unified, there must be one language and one culture, emphasizing the need for uniformity and in cases when a language becomes a political issue it is perceived as a potential tool for fragmentation and separatism. Dr Aurelie Jouber notes that this is a pretty simplistic view of language and culture and that some individuals’ lack of empathy pushes people to think that minority languages are a threat or unimportant.

To them that a language is a thread is the worst case scenario but the overall thought of minority languages being useless is pretty harmful too. Xxx states that “A lot of people ask themselves, if languages are small, why should we care about them? But I think that this is a very instrumentalizing way of viewing languages. A lot of times languages are perceived solely as instruments for communication and their cultural and identity-rich dimensions are often overlooked. However, when viewed as integral cultural artifacts and essential components of individuals’ identities their importance transcends numerical measures. “Whether a language is spoken by one person, a thousand people or a million, its defense becomes crucial as it represents a fundamental human right. Defending languages then becomes a matter of defending the rights of individuals or small groups and therefore Europe should be pushed to fulfill its commitment with multilingualism without leaving anyone behind.