In November 2024, the collapse of the Novi Sad train station ceiling killed 15 people and exposed deep-rooted issues of corruption and governance in Serbia. This tragic event is more than just a failure of infrastructure; it’s a symptom of systemic corruption, negligence, and mismanagement. The repercussions stretch far beyond Serbia’s borders, posing significant challenges to its European Union (EU) accession efforts.

Belongs to Agouna Tia

The Novi Sad Train Station Collapse: A Tragic Symbol of Negligence

Shattered concrete, Twisted steel beams jutted from piles of rubble, and thick clouds of dust blanketed the air—this was the apocalyptic scene that greeted rescue workers at Novi Sad train station on November 1, 2024. Ambulances wailed through the city as firefighters braved unstable ruins, their faces streaked with soot and sweat. Among the chaos lay the lifeless bodies of 15 victims underneath, while dozens of injured clung to life amidst the debris. The air was heavy with the acrid scent of burning wires, and the anguished cries of survivors echoed through the cold autumn morning.

The renovation of the Novi Sad train station, completed in early 2023, was promoted as a flagship infrastructure project. However, post-collapse investigations revealed a damning trail of negligence: substandard materials, poorly supervised construction, and opaque public procurement practices.

“Public procurement is always sensitive to corruption, especially in candidate countries,” said Dr. Nathan, an expert in European law and governance. He highlighted that mismanagement of funds and lack of transparency in projects like Novi Sad demonstrate “why governance reforms are critical for EU accession.”

Belongs to Agouna Tia

According to the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE), infrastructure failures like the Novi Sad train station collapse often stem from systemic corruption, inadequate supervision, and use of substandard materials. ICE emphasizes that “without transparency and rigorous oversight, public infrastructure projects remain vulnerable to catastrophic failures” (ICE, 2024). This underscores why Serbia must prioritize reforming procurement and oversight to protect public safety.

Corruption in Serbia: A Persistent Systemic Issue

The train station renovation was celebrated as a major infrastructure milestone. Yet, detailed investigations by both the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE, 2024) and independent Serbian investigative journalism network BIRN (2024) revealed critical failures—substandard construction materials, inadequate oversight, and non-transparent procurement processes. ICE specifically noted that such governance weaknesses are common indicators of broader systemic corruption, confirming the project’s failure as symptomatic of deeper governmental issues.

Corruption remains a defining challenge in Serbia’s political and economic landscape. According to Transparency International, Serbia ranked 96th out of 180 countries on the Corruption Perceptions Index in 2023, marking a significant decline compared to its regional peers. An estimated 20% of all public procurement contracts are manipulated, costing taxpayers billions of euros annually. These practices contribute to a widespread perception that corruption is more entrenched now than at any time since the fall of Slobodan Milošević. Infrastructure projects, such as the Novi Sad station renovation exemplify this issue.

Despite high-profile arrests, including the Minister of Construction, activists argue that these actions are superficial. “Accountability can’t just mean a few scapegoats,” said Radovan, an editor at the Center for Research, Transparency, and Accountability (CRTA), one of Serbia’s leading NGOs. “The entire system enabling this culture of corruption needs dismantling.”

The Novi Sad tragedy ignited one of the largest protest movements since the fall of Slobodan Milošević. Tens of thousands of demonstrators flooded the streets of Belgrade and Novi Sad, demanding sweeping reforms in public procurement, judicial independence, and media freedom.

Protesters painted symbolic red handprints on government buildings to signify the blood of victims on the hands of corrupt officials. Radovan, speaking on the protests, noted, “The scale of these demonstrations is unprecedented in recent years. Citizens are no longer willing to tolerate the abuses that have led us here.”

Belongs to Agouna Tia

Serbia’s EU Accession: A Stalled Journey

Serbia’s EU membership prospects hinge on meeting stringent governance, transparency, and anti-corruption benchmarks outlined in the Copenhagen Criteria. While Serbia has made some progress, systemic issues remain glaring roadblocks.

On March 16, 2025, a massive protest in Belgrade, Serbia, attracted between 275,000 and 325,000 participants, making it the largest rally in the country’s history. The demonstration was sparked by public outrage over the deaths of 15 people in a railway station collapse in Novi Sad, which protesters attribute to government corruption and negligence. Despite the government’s claim of only 107,000 attendees, participants, including students, farmers, and taxi drivers, demand accountability and transparency regarding the renovation of the station. Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic faces increasing pressure as protests continue, with demonstrators insisting on justice and reform, while he maintains his position against resigning.

De Launey, G. (2025, March 15). Serbia’s largest-ever rally sees 325,000 protest against government. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cx2g8v32q30o

Serbia’s EU accession hinges fundamentally on governance and anti-corruption reforms as outlined in the Copenhagen Criteria. A recent report by the Center for European Policy Studies (CEPS, 2024) emphasizes that Serbia’s stalled accession progress is primarily due to persistent issues in judicial independence and procurement transparency. Furthermore, Transparency International’s 2023 report clearly demonstrates Serbia’s declining anti-corruption performance, highlighting the urgent need for substantial internal reforms to satisfy EU benchmarks.

EU Requirements vs. Serbia’s Status

Source: EU Commission Progress Reports (2024).

| EU Requirement | Serbia’s Status |

| Fully independent judiciary | Judiciary influenced by political interference |

| Open, fair, and competitive processes | Public procurement lacks transparency and accountability |

| Robust anti-corruption institutions | Weak implementation and enforcement |

| Free and independent press | Declining; government controls narratives |

A Timeline of Serbia’s EU Accession

- 2005: Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) negotiations launched.

- 2009: Serbia applies for EU membership; visa-free travel to Schengen countries granted.

- 2012: Serbia granted EU candidate status.

- 2013: EU endorses accession negotiations; SAA enters into force.

- 2014: Accession negotiations formally begin.

- 2021: 22 of 35 chapters opened, including Green Agenda and sustainable connectivity.

- 2024: Progress stagnates due to corruption and governance issues.

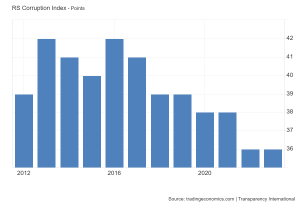

According to the latest Corruption Perceptions Index from Transparency International, Serbia scored 36 out of 100 in 2023 (where 0 is highly corrupt, and 100 very clean)—indicating high levels of perceived public sector corruption. While an improvement from the country’s all-time low of 23 points in 2003, Serbia’s corruption index has averaged just 35.71 over the past two decades, suggesting the problem remains entrenched. Transparency International’s annual ranking, which scores countries from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean), placed Serbia at 104 out of 180 nations surveyed in 2023. The data underscores the need for the government to intensify anti-corruption efforts to restore public trust and improve the business climate.

What Lies Ahead for Serbia?

The collapse at Novi Sad train station has shone a harsh spotlight on the systemic failures plaguing Serbia. The protests and international scrutiny have amplified calls for reform, but questions remain about whether Serbia’s leadership can deliver real change.

As Radovan observed, “This isn’t just a moment of reckoning—it’s an opportunity. The public is awake, and the world is watching.”

Whether this momentum leads to transformative reforms or fizzles out will depend on the government’s willingness to prioritize the needs of its citizens over entrenched political interests. For now, the memory of Novi Sad lingers as both a warning and a call to action for a country at a critical crossroads.