HIV, AIDS and other ghosts haunt the city of Berlin. While medical progress has significantly reduced the number of new infections, hate crimes against LGBTQ+ people are on the rise—often fueled by the lingering stigmatization of the AIDS crisis. To make matters worse, the Berlin senate is scaling back financial support. But in hard times, the queer community knows where to find a safe space.

Fresh Flowers lie beneath the memorial honoring queer people killed during the Nazi era. The pink triangle, once a symbol of persecution, has become a powerful emblem of queer resilience. The red tulips, roses and candles still placed recently at this site aren’t only a nod to history—they were laid there in mourning after a recent hate crime in which HIV and Dresden, a sign of right-wing groups in Germany, were sprayed in red over the mural.

For Berlin drag queen and tour guide Anna Klatsche, the attack struck close to home. “I was in shock. This spot is very dear to me. I walk past it every week with the Queer Kiez Tour,” she tells me and the group she is guiding through the city today. Though the hateful graffiti was quickly removed, the trauma lingers. The past, it seems, is never too far behind.

Anna Klatsche

Anna Klatsche

“You see it in the people”

In the 1980s, during the height of the AIDS epidemic, queer life in Berlin was pushed into the shadows. Police raids on queer bars were common until late in the decade. It took years for queer venues to open their doors—literally—to the streets again. The bar Dreizehn was one of the first to do so; to this day a lot of gay bars cannot be entered without ringing a doorbell. And while gay men were dying every day in Berlin, little public concern was shown for all the cultural diversity that was vanishing at that time.

The epidemic took an enormous toll on the queer community. Nearly every gay man in Berlin lost someone. Anna Klatsche used to work at a queer advice center and has talked to many people who lived through that time. When I ask her if you can still see the AIDS crisis in Berlin somehow, she says: “You see it in the people who still live today in this city”. They are the witnesses of this times and hold the memory alive. Public indifference was rampant. This erasure led to the founding of the Schwules Museum Berlin (Gay Museum), a response to the cultural void created by the crisis. As board member Heiner Schulze recalls, “It was kind of a response to that period of struggle.”

In times of struggle the queer community comes together. Different institutions like Mann-O-Meter or the Berliner Aids Hilfe which are important in the fight against HIV were founded during the peak of the AIDS crisis, which somehow, as Heiner Schulze thinks about it, has helped the queer community to make gay life and issues more visible. Otherwise, they might never have got the financial support from the government which helped them to provide for their community. “Germany had a more liberal approach to AIDS, in comparison to countries like France, with a lot of awareness being spread”, says Heiner Schulze. He speculates that this was also a reason why the numbers of new HIV infections never sky rocketed as high as in more conservative countries.

Ghostbusters, PEP and PREP

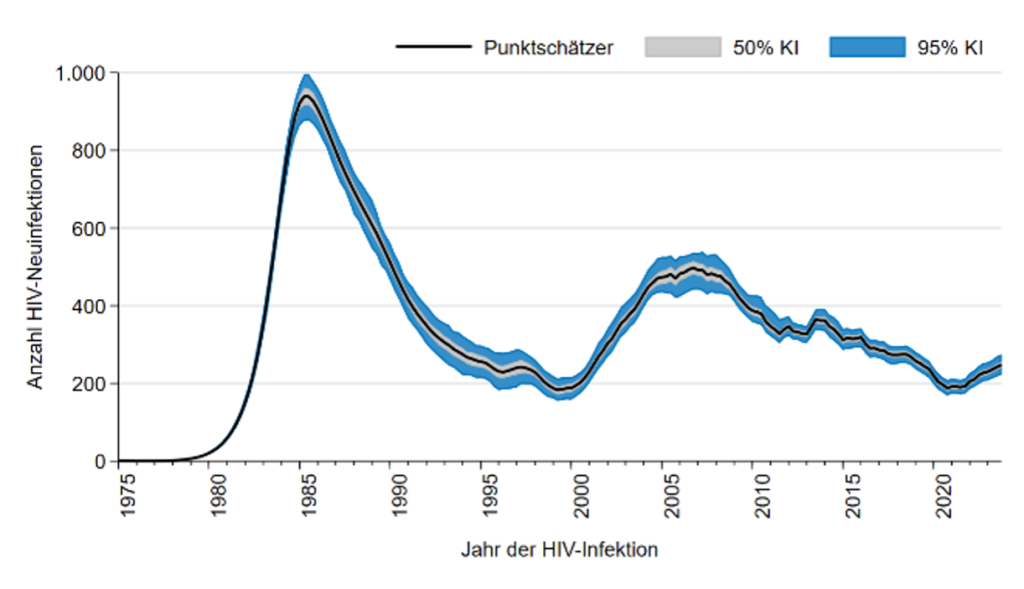

A new generation is growing up in a different world. The new Robert Koch Institut statistics show a decline in new infections over the last centuries, and for Europeans with a positive HIV diagnosis, good treatment s more accessible than ever. Medical advances have also changed the landscape. In 1998, a man known as the first “Berlin patient” was successfully cured of HIV through an experimental therapy at Charité hospital. More recently, a second Berlin patient was cured through a stem cell transplant, presented at the 2024 AIDS conference in Munich.

Today, medications like PEP (Post-Exposure Prophylaxis) make it possible to live a long, healthy life with HIV. But also, the fear of becoming positive is not the same anymore, taking the PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis) medication prevents a possible infection, making it safe to have sex with HIV positive people. Most importantly, HIV is not a queer problem; it affects heterosexual people as well.

“Who cares?”

Today, the Gay Museum embraces all queer identities—lesbian, trans, bi, ace, and BIPOC stories included. Yet, the threats haven’t disappeared. Quite the opposite. In a chilling reminder of lingering hate, bullets were fired at the museum’s windows on the 24th of February 2023. There was no robbery, this an aggressive symbolic message: You are not welcome here. Schulze remembers the attack vividly. “This was hate; nothing else.”

Heiner Schulze

Heiner Schulze

According to Berlin’s official report on anti-queer violence, 588 queer-hostile offenses were recorded by police in 2023—an all-time high. The real number is likely higher. Sven Lehmann, the Federal Government Commissioner for the Acceptance of Sexual and Gender Diversity, stated in the ILGA Europe report that three to four queer people are assaulted daily in Germany.

The hate isn’t just on the streets. Online platforms serve as breeding grounds for radicalization. Discrimination, threats, and slurs against queer people are part of their daily digital experience. In real life, attacks often occur in central nightlife areas like Mitte (24.7%) and Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg (12.9%). These are no easy times to live in: Rising far-right influence across Europe—including recent anti-LGBTQ+ laws in Hungary—threatens the progress made. Even within queer spaces, conservative factions like TERFs and right-leaning queer politicians are gaining visibility, complicating the fight for solidarity.

We are midway through our Queer Kiez Tour and gather in front of El Dorado, the once famous Varieté theatre that served as a sanctuary for trans people and other queers. Anna Klatsche is telling us about the times of the golden twenties when Berlin was a place of ecstasy and freedom for those who were looking for it. Suddenly a man interrupts her, a bottle of wine shaking in his hand; “Who cares?”, “You’re talking shit!”. Anna Klatsche continues her talk, trying to ignore the drunk man, but he comes closer and closer, muttering angrily and making for a tense atmosphere. It takes the whole group to drive the man away. Even though our guide had told us about the everyday discrimination she has to experience when she is in drag, it feels frightening, chilling and sad to really experience it.

Heiner Schulze

Heiner Schulze

Communication is key

The Queer Kiez Tour ends in the bar Der neue Oldtimer and everyone is drinking together. It is a big group and many different people have participated in the excursion, most of them from Berlin. Not all of them are gay. Stigmatization and discrimination, concerning HIV, gay, trans, queer topics are nearly always related to lack of knowledge and experience. Prejudice stems most often from ignorance. Education, studies show, can change minds.

A 2016 Berkeley-Stanford study found that face-to-face conversations can significantly reduce transphobia. Yet a night out with a drag queen or meeting someone with HIV to have an open talk is not a possibility for everyone. That is one reason why it is so important for the media to cover HIV related issues and to fight myths, as a GLAAD HIV Stigma Report (2022) study has found.

Global statistics on new HIV infections reveal higher numbers especially in countries where educational work is not funded, or legalized discrimination makes people afraid to get tested. In Berlin the institutions have been funded well over the last decades but are under threat – many queer institutions are also affected by the budget cuts of the Berlin senate. This threatens not only the institutions but also the queer community and Berlin’s reputations, as Heiner Schulze puts it.

Heiner Schulze

Heiner Schulze

Berlin continues to be the queer flagship store of the world. But there are cracks in the building, and they are getting bigger. With right wing parties in Germany becoming stronger and the political atmosphere in Europe intensifying. Berlin is no longer the safe haven it used to be. The queer community in Berlin sadly has lots of experience on how to keep going even when the wind of hate is blowing stronger, and the political waves are crashing high. “They care for each other and build communities and institutions for themselves if no one else will do it with them”, says Anna Klatsche.

Anna Klatsche

Anna Klatsche

The Queer Kiez Tour and the Gay Museum of Berlin were both founded without governmental support, and are proof that the queer community is very well capable of continuing to fight this battle. Diana Ross’s “I’m coming out” is playing on the radio: In the last bar, Anna Klatsche drinks a glass of champagne, her wig elegantly floating on her shoulders. She smiles, and she laughs, and you’re reminded of what queer life is supposed to be.