As of January 2025, Austrian shoppers are adjusting to a new habit: buy a drink, pay a deposit, bring the bottle back. The launch of a nationwide deposit return system marks one of the country’s most ambitious efforts to address plastic waste and meet EU recycling targets but its success depends on more than machines and infrastructure.

According to Eurostat, in 2022, Austria recycled only 25% of plastic packaging, which is well below the EU average of 41%. The new deposit return system aims to close that gap — and Vienna is at the center of it. Across the capital, reverse vending machines are appearing in supermarkets, logos now flag bottles that carry a €0.25 deposit, and local policy is pushing for a bigger change.

From checkout to habit change

In many European countries, bottle deposits are old news — but in Austria, they’re just getting started. Since January 2025, shoppers have been paying a €0.25 deposit on most plastic bottles and cans, refundable upon return at reverse vending machines. While new to Austrians, the system follows well-established models already in place across much of the EU.

Austria’s deposit return system (DRS) was years in the making and aims to boost recycling rates dramatically. Before its launch, about 70% of plastic bottles were collected. According to the article “Einwegpfand: What you need to know about Austria’s new bottle deposit system”, now, the country hopes to hit 80% by the end of 2025 and 90% by 2027 — targets that mirror the EU’s Single-Use Plastics Directive. However, reaching those numbers depends not only on machines and infrastructure but also on changing daily behavior.

A 2025 survey by Recycling Pfand Österreich found that 82% of Austrians support the DRS, with 70% believing it will reduce littering and contribute positively to environmental protection. Despite this strong support, a separate survey conducted by TQS on behalf of Fritz-Kola revealed significant public confusion, notes Vienna.at. Notably, 30% of respondents did not know how to identify reusable bottles, and 40% were unaware of what happens to bottles after they are returned. These gaps in knowledge were especially pronounced among younger people aged 16 to 29.

A national system, thousands of machines

As stated by Greenpeace, Austria produces an estimated 1.6 billion plastic bottles each year — and nearly 900,000 tons of plastic waste. To tackle the growing pile, the country is betting big on its new deposit return system (DRS). Within weeks of launch, more than one million bottles and cans had already been fed into machines. By spring 2025, more than 11,400 return points had been installed across Austria — including around 6,000 reverse vending machines in supermarkets, petrol stations, and corner stores, reported Austrian Press in the article “New deposit system since January 1: One million bottles and cans have already returned”.

The rollout marks one of Austria’s most ambitious environmental undertakings to date — requiring major logistical coordination between retailers, recyclers, and the nonprofit operator EWP Recycling Pfand Österreich gGmbH. Supermarket chains like Billa, Spar, and Hofer had to reorganize floor plans, train staff, and manage customer questions — all while staying open for business.

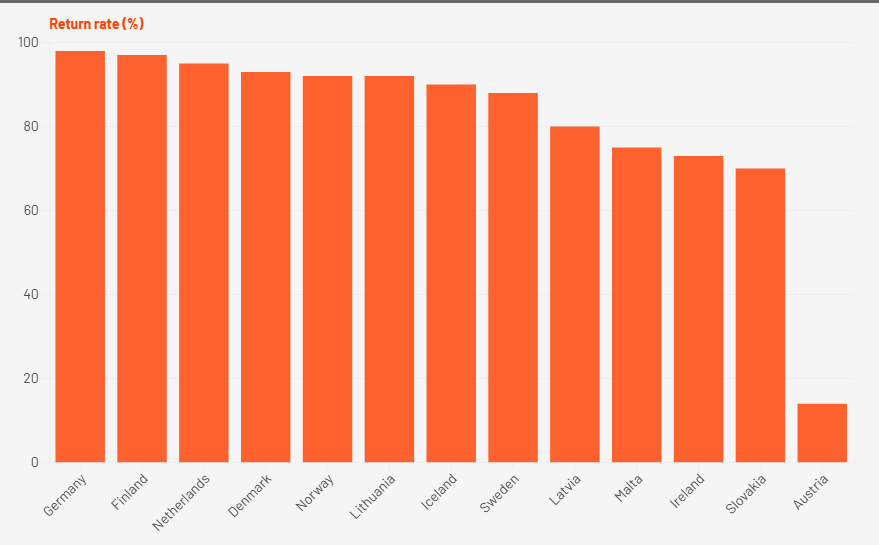

But building the network was only half the job. Austria has the highest supermarket density in Europe — giving it a clear advantage for making bottle returns part of daily life. By April, return rates remained low — just 14%, based on figures cited by Vienna.at in the article “Disposable deposit system in Austria: Millions of packaging already returned”. In part, that’s because the system is still in its “learning phase,” according to Austria’s Ministry of Climate Action. Public information campaigns and clearer signage are being ramped up to help boost participation.

Vienna: Austria’s Testing Ground for Deposit Reform

With nearly 2 million residents and the country’s densest network of supermarkets, Vienna is at the heart of Austria’s bottle return experiment. The capital not only serves as the logistical backbone of the new system — it’s also a place where design decisions are being stress-tested, and not always welcomed. One example: Vienna’s municipal waste authority, MA 48, rejected the idea of attaching bottle deposit rings to public bins. The reason? Evidence from cities like Berlin and Cologne showed that the rings encouraged littering, not recycling — turning public spaces into informal bottle markets, reports Vienna.at in the article “That’s why there will be no deposit rings on trash cans in Vienna“.

But Vienna isn’t just a test site. It’s also setting the pace on climate action. According to the Center for Public Administration Research’s European Governance and Urban Policy, under Vienna’s Climate Act, the city now uses a climate budgeting system that tracks the emissions impact of public investments, including infrastructure like bottle return machines — aiming to align every euro spent with its 2040 climate neutrality goal. That effort includes a pioneering climate budgeting system, where every public euro is evaluated for its carbon impact. Under this system, even investments in DRS infrastructure — like reverse vending machines and collection logistics — are tracked for their emissions footprint. If the model proves effective, it could inspire similar systems in other Austrian municipalities.

From Forest Waste to 90% Returns: Lithuania’s Deposit System

Looking beyond Austria offers a useful benchmark, especially when comparing narratives of early confusion versus long-term results. “In 2016, the system was introduced as a solution to the growing environmental issue of beverage packaging polluting nature, forests, parks, and lakesides,” states GrazintiVerta.lt, the official DRS platform in Lithuania. “Only around 30% were properly collected which is very little,” said Gintaras Varnas, head of Užstato sistemos administratorius (USAD), the non-profit that manages the system. “People always care about getting their money back — some more, some less but the drive remains steady.”

Inspired by Scandinavian models with return rates above 90%, the Lithuanian government passed legislation requiring industry-wide participation. “It wasn’t about convincing anyone,” Varnas noted. “A law was passed… If you want to sell beverages in containers that fall under the deposit system, you must join the system. You have no choice.”

According to Varnas as of 2024, Lithuania’s return rates remain above 90%, and visible litter has decreased nationwide. By comparison, Austria is only now implementing its nationwide DRS in 2025. “This system is never voluntary, at least not in Lithuania. Of course, when laws change and new responsibilities are introduced, some resistance is normal. But the obligations remain,” states Varnas.