In the heart of one of Europe’s most livable cities lies a grand social experiment nearly a century old. Known as Red Vienna, the city’s unique housing system has long stood as a global beacon of equitable urban planning. Born from the ruins of World War I and guided by a vision of socialist reform, this system built not only homes, but a cultural identity rooted in stability, dignity, and inclusion.

Today, that identity is under pressure.

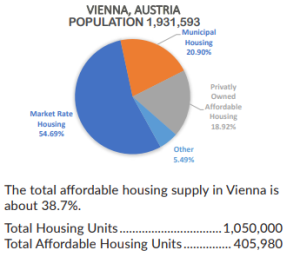

While more than 60% of Viennese still live in publicly subsidized or cooperative housing, rising property prices, political shifts, and private speculation are testing the durability of a model once thought untouchable. As Vienna faces the challenges of the 21st century, many ask: can Red Vienna still deliver on its promises of affordable, high-quality housing for all?

A Revolutionary Blueprint

Red Vienna emerged between 1920 and 1934 as the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP) took control of the city’s new autonomous status within Austria’s federal system. The socialist government quickly prioritized one issue above all others: housing.

As city official Schnabl Bojan-Ilija explained in an interview, the postwar housing crisis was dire. “People didn’t rent flats—they rented beds for shifts during the day,” he said. Vienna was the “city of tuberculosis,” plagued by overcrowding and poor sanitation.

Kindergarden at the Karl-Marx-hof

To fix this, the city introduced progressive taxes on luxury goods and housing profits, using the revenue to build 60,000 municipally owned flats in just a decade. These Gemeindebauten, like the iconic Karl-Marx-Hof were more than housing. They featured kindergartens, clinics, libraries, and vast green courtyards. Architects from the former empire designed them with ventilation, sunlight, and dignity in mind.

This model wasn’t limited to the city’s outskirts. Social housing appeared in affluent districts and even near landmarks like St. Stephen’s Cathedral. This ensured political integration and a sense of belonging for working-class residents. According to Bojan-Ilija, “Viennese don’t aspire to home ownership like elsewhere. Rental is safe, affordable, and lifelong.”

Present-Day Reality: Strong but Strained

Today, Vienna still offers lessons to the world. More than 74% of the city’s housing is rented, and nearly half is publicly managed or subsidized. Rent regulation ensures affordability, with legal protections dating back to 1917 still influencing the market mindset.

But the pressure is building.

While public housing remains stable in older districts, private development and gentrification surge elsewhere. Donau City, for example, symbolizes a turn toward high-rise luxury living and public-private partnerships, far removed from the Red Vienna ethos.

According to Euronews (2024), residents in newer developments voice concerns: “Waitlists are long. Flats are smaller. It’s not what it used to be.” Despite these changes, over 220,000 Viennese still rely on municipal housing. But the demand far outpaces supply.

Figure via resources.gpla.co: Breakdown of Vienna’s Housing Market (2024) Municipal housing makes up 20.9% of all housing in Vienna, while another 18.92% is affordable but privately owned. Just over half of the city’s housing is market rate.

Who Gets In? And Who Gets Left Out?

Eligibility for public housing is based on income and residency requirements, but critics argue the system

struggles to serve everyone equally. Migrants, low-income families, and young professionals often face longer waits or are redirected to cooperative or subletting markets.

Studies like Essletzbichler & Forcher (2021) show how shifts in the housing system correlate with political alienation. In neighborhoods with reduced public housing, support for right-wing populist parties has grown—suggesting that housing inequality feeds broader social rifts.

Children playing at the Karl-Marx-hof

Still, the city’s average rents remain far below those in most European capitals, thanks largely to legal rent caps and public competition. The psychological effect is immense: “You can build your life here,” said Bojan-Ilija. “There’s no fear of being priced out.”

Policy and Politics: Tipping Point or Turning Point?

Vienna’s municipal leadership, still largely Social Democratic, remains committed to public housing. Wiener Wohnen, the largest public landlord in Europe, maintains nearly 220,000 units. But internal documents show growing challenges around funding, maintenance, and modernization.

As Novy et al. (2001) noted, neoliberal influences have crept into policy. Real estate investors increasingly shape urban design, and public-private ventures have grown, especially since the 2008 financial crisis.

At the same time, the International Building Exhibition (IBA_Vienna) promotes “New Social Housing,” with innovation in cooperative models and climate-resilient design. However, critics worry this still favors middle-class aesthetics over working-class needs.

Why It Matters Beyond Vienna

Globally, cities from Seoul to Barcelona look to Vienna for answers. The Vienna Model has been featured in exhibitions from Los Angeles to Tokyo as a counterpoint to speculative housing bubbles.

But replication isn’t easy. As Wagenaar & Wenninger (2020) argue, Red Vienna succeeded because of a specific political culture and governance model that fostered long-term thinking. Without these foundations, superficial copies may fail to deliver.

If Vienna allows its own model to erode, the consequences could ripple across Europe.

Renewal or Retreat?

Red Vienna stands as one of the 20th century’s most visionary urban experiments. Its legacy is visible not just in architecture, but in social cohesion, affordability, and a profound sense of place.

But the pressures of globalization, market liberalization, and demographic change are testing its foundations. Whether Vienna can preserve and evolve this legacy depends on political will, sustained public investment, and a reassertion of housing as a right, not a commodity.

As Bojan-Ilija put it, “Red Vienna isn’t a museum. It’s a promise. But promises need to be kept.”