With increasing threats, the Dutch government is urging citizens to be prepared for a possible crises, from power outages and floods to hybrid attacks. But defending society isn’t just about national defense budgets or home emergency kits. It’s also about a resilient society where people trust each other, and how communities organize themselves.

The SCP (Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau), a Dutch government research institute, highlights the importance of resilient communities in times of crisis. “Research shows that communities where people trust each other and are willing to help one another cope better with unexpected events and tend to be more creative,” writes Karen van Oudenhoven, director of the SCP and professor of social resilience at the University of Amsterdam. “These individuals feel a sense of responsibility for their community and are quicker to take collective action.”

“True resilience is built locally,” Van Oudenhoven adds. “The government can’t deliver groceries to a neighbor during a lockdown, that’s up to us.”

Crisis management researcher Kenny Meester warns that physical goods can provide a “false sense of security.” He argues that gear is only as good as the person using it. “Buying an emergency kit is easier than taking a first-aid course,” Meester notes. “You can buy a tent, but if you’ve never pitched one, you still have a problem. Having the gear is necessary, but it is not sufficient on its own.”

Some Dutch municipalities are taking this lesson into practice. With no national blueprint, they have experimented with different approaches to connect residents, local organizations, businesses, and volunteers. On August 28, the Association of Dutch Municipalities (VNG) issued a guideline for resilience and preparedness in local communities, giving municipalities examples and practical advice.

According to crisis expert Meester, social resilience starts with a “mental exercise” of mapping the talents already present in your street. Instead of everyone being an expert in everything, a resilient community relies on collective knowledge. “I don’t need to know first aid if I know someone in my street is a nurse,” he explains. “And others don’t need to know how to communicate in a blackout because I am a ham radio operator. When we bring all our gear and knowledge together, our collective resilience increases.”

The guideline for municipalities draws lessons from Ukraine. The Russian attack has shown how critical local governance can be in a crisis. Ukrainian municipalities relied on residents, volunteers, businesses, and NGOs to maintain essential services under extreme pressure. According to the VNG, towns with strong local networks and collaboration between government and society proved far more resilient than those without.

The challenge in the Netherlands is that the country is historically built on resistance using infrastructure like dikes to keep threats out. Meester points out that this makes the population less practiced at “resilience,” or the ability to take a hit. “In Jakarta, they deal with floods every month and have found ways to help each other,” Meester says. “We are good at stopping things, but we need to learn how to handle the blow when something actually goes wrong.”

According to the crisis experts, being prepared is more than emergency plans or infrastructure. It depends on trust, coordination, and active engagement across society. Building resilience means creating networks where everyone knows their role, neighbors support each other, and communities are ready to act collectively when disaster strikes.

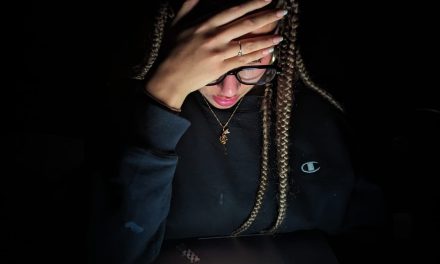

Example of what building resilience can look like: seeking contact with your neighbour. Photo: Sammy Jo