Malta, a small European Union member state and former British colony, has in recent years promoted itself as an international hub for private higher education. The country has attracted students from across the world, particularly from outside Europe, by offering degrees that are recognised within the European Union.

For many of these students, studying in Malta represents a significant financial and personal investment, often made in the expectation of improved career prospects and legal recognition across Europe.

But for a growing number of them, that promise has not been fulfilled. Instead, they say they were misled and financially exploited by the institutions they trusted with their futures.

Just outside Malta’s busy urban centres, on a quiet, sand-coloured street of limestone buildings, there is little to suggest an international university hub. At the top of a short staircase, behind a modest entrance, is where the International European University once operated.

It is this address that has become the centre of mounting complaints from former students in multiple countries, raising broader questions about oversight and accountability in Malta’s private education sector.

The rise and fall of the International European University

Founded in Ukraine in 2019, the International European University (IEU) presented itself as a modern, international higher education institution, offering programmes in business, management, international relations, and medicine.

In 2023, the university relocated to Malta due to the war in Ukraine, securing a temporary licence from the Malta Further & Higher Education Authority (MFHEA). It operated within the country’s fast-growing private education sector, which actively targets foreign students.

Concerns about IEU’s transparency quickly emerged. Students reported difficulty obtaining clear information, and online platforms such as Reddit were filled with warnings, alleging the university was a scam. Many students said they never received refunds for tuition fees, often amounting to several thousand euros, after failing to obtain Maltese visas.

After concerns about the university’s transparency began to surface, Times of Malta journalist James Cummings contacted the University. “We contacted the university repeatedly to try to get answers, but they were not very forthcoming in their responses,” Cummings said. “When we visited the campus, we were not able to get clear answers to many of our questions.”

Shortly after these concerns were highlighted in the media, the university’s licence was revoked. “According to the authority, the institution failed to meet the criteria set out in an earlier audit. My understanding is that conditions had been attached to its licence, and when those conditions were not met, the licence was withdrawn,” Cummings ads.

Location where the IEU was previously located, but where a new private school is currently established. Photo: Chimène de Jonge

The closure came as a shock to students, many of whom arrived to find the campus shuttered, with no guidance on the status of their studies or how to access their academic records. For international students, the situation was even more critical. Those from outside Europe discovered, via an email from Identità, that their student visas had also been revoked.

“Staff had promised to meet the students, but no one showed up. What was meant to be a meeting quickly turned into a demonstration. Once all the students were gathered, a sense of solidarity emerged, and emotions ran high.” James Cummings was on site reporting at the time when this meeting turned into a demonstration.

“I lost both time and money”

A former international medical student at the IEU, who requested to remain anonymous for safety reasons, described a confusing and frustrating journey across IEU’s campuses. “When I started the journey, I had originally sought admission at their main campus in Ukraine before the war. When the war started, they transferred me to their Polish campus, and later, for reasons I only later understood, to their campus in Malta, where I received lectures before their licence was revoked,” they said.

The student explained that the Polish campus had never been licensed, a fact that had been kept from them. They also criticised the quality of teaching.

“Even the theoretical aspects were lacking. For my year, we were not taught the practical part at all, although some people may have been. We later found out that the university’s licence only covered theory, which completely contradicted what we were told during admissions.”

The school was not transparent with their students about what they would learn in school and where they would get their degree for. The student says that it never felt that the school was in it for the education, in their word there were always in it for the money. “Sometimes I was the only one in the classroom from all the other students. This was not because they didn’t want to come to school, t

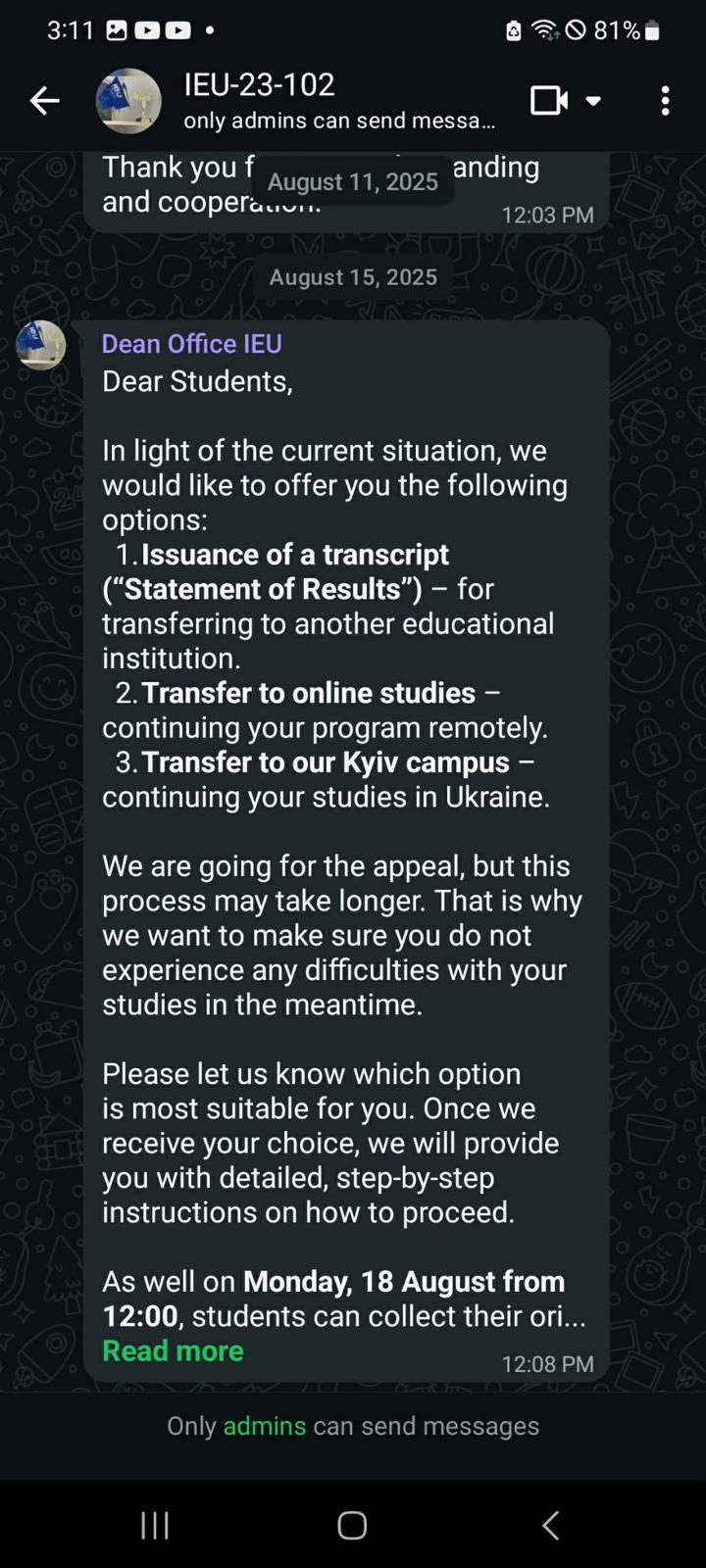

Screenshot of a message from the IEU group chat, showing the options that were given to their students. Date of the message: 15 August 2025.

his was because they were not allowed in anymore. The school would ask students to pay their debts, if we didn’t, we weren’t allowed to attend classes.”

When the Maltese licence was revoked, communication was minimal. “We found out the school’s licence had been revoked after it was already done. There was very little communication and no transparency”. Later, via a WhatsApp group with the school the students were offered a few options:

- Continue their school online

- Transfer to the Ukraine Campus

- Request transcripts to move to another university

Returning to Ukraine, where there is still an ongoing war happening, was one of the options presented to the students. “I don’t know anyone who chose it. Most students were left in limbo, not knowing what to do next. I chose to request my transcripts and try to transfer to another university. But when I tried to use them, I was told there were errors and that I would have to repeat the year”, the student adds that they feel scammed by the school, “In the end, I lost both time and money. I personally lost about €10,000.”

Concerns over private colleges in Malta extend beyond IEU

A current student from India at a different private institution in Malta, who requested to remain anonymous for fear of being expelled, tells his view on the situation in Malta.

“In Malta, despite the country being only about 316 square kilometres, there are private institutions in almost every corner, including my own,” the student explained. “A large number of international students come to enrol in courses such as Elderly Care or Carer programs. Tuition fees for these courses are very high, ranging from €6,000 to €7,000 for short durations of three to six months, while the level of the course is just 3 out of 5.”

According to the students, most of these institutions are small and do not function like proper colleges. Online classes are a regular thing, and the schools fail to meet acceptable educational standards. Also, the housing that students are promised upon coming to Malta does not match what they find upon arrival on the island.

“Over time, it has become clear that education is being treated as an easy source of income rather than a genuine learning experience. I personally faced many difficulties at the beginning of my student journey. Several promises made during the admission or interview process were not fulfilled, and students are charged high tuition fees despite receiving low-quality education.”

They added that complaints about these institutions are widespread. “Many students say the focus is not on education, but on making money for the schools.”

The Malta Further & Higher Education Authority

The MFHEA, the body responsible for licensing and regulating private colleges in Malta, has itself come under intense scrutiny.

In late 2024, the authority’s bid to be listed on the European Quality Assurance Register for Higher Education (EQAR) was rejected after an external review found it partially compliant with key European quality standards.

Membership of EQAR is widely used by universities, employers and accreditation bodies across Europe as a benchmark of academic credibility. Without it, degrees awarded by institutions regulated by MFHEA risk being not recognised abroad, with students facing uncertainty about whether their qualifications will be accepted in other European countries.

Sign with the MFHEA logo at their office in Malta. Photo: Chimène de Jonge

Critics, including politicians and professional bodies, say this situation undermines confidence in Malta’s higher education sector and has left both local and international students exposed to potential barriers when seeking work or further study elsewhere in Europe.

The MFHEA did not respond to requests for comment on these issues.

Malta’s private education sector

According to reports by the European Commission and Eurydice, Malta’s unusually large private education sector is largely the result of deliberate policy choices rather than regulatory neglect. Successive governments have promoted education as part of the country’s service-based economy, alongside tourism, financial services and online gaming, positioning Malta as an accessible entry point to Europe for non-EU students, particularly in fields such as business, IT and health.

Research from Eurydice also notes that Malta has a relatively high proportion of private higher-education providers for its population size. Compared with larger EU countries, where multiple layers of accreditation and regional approval are required before institutions can award recognised degrees, Malta’s centralised licensing system is simpler and faster, making it easier to establish private institutions.

On Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, Malta consistently ranks among the lowest-performing EU countries in terms of perceived corruption. Analysts say this broader governance context may weaken regulatory independence and oversight. Investigative journalists and professional organizations have repeatedly warned that such conditions can allow problematic institutions to continue operating for years before enforcement action is taken.

Knights College

Several students affected by the closure of the IEU have been giving a scholarship by another private schools, Knight College. The principal of the school, Kristina Galea Borg, talks about this process in the video interview below.

The situation now

The International European University is an existing institution, but it no longer holds a licence to operate in Malta. Despite this, its website continues to accept new applications for the Malta campus, requesting sensitive information such as passport numbers, without any notice or clarification about its closure on the island. Students who previously enrolled, or attempted to do so, report feeling misled, citing financial and academic losses.

Several months after Maltese authorities withdrew the university’s licence, a new private school has already moved into the same premises. While the original institution no longer operates in Malta, the lingering online presence and rapid replacement have left former and prospective students uncertain about the legitimacy of educational offerings on the island.