Walking into any art academy in The Netherlands one would be struck by the high number of female students roaming the hallways or setting up their latest pieces on the walls. But looking beyond a façade of gender equality and diversity the cracks start to appear.

Female artists seem to thrive within higher art education, catering for 70% of the student body. Yet, they still struggle to break the glass ceiling compared to their male colleagues after graduation. A survey conducted by The School of Missing Men amongst alumni of BEAR—BA Fine Art ArtEZ Arnhem shows that male artists are more likely to successfully apply for a grant or a residency, or realize an exhibition, while female art graduates often switch career path choosing a teaching or research trajectory. Yet, where does the road start to become steeper for women in the art world? What are the invisible hurdles foreign to their male counterparts?

Higher art education: planting the seed of inequality

During the conference held at the Arnhem-based cultural organisation ArtEZ Studium Generale, art teacher and philosopher Petra Van Brabandt uncovered a reality of sexism in art education. She uncovered the problematic system of ‘no complaint, no problem’. Van Brabant laments the fact that individual voices are easy to be dismissed; only collective complaints don’t pass unheard. But gathering consensus when you reside outside of the dominant group is no piece of cake. In fact, most educational institutions still rely on a prevalently white homogeneous staff and student body, making it impossible to speak up collectively. Van Brabant also brings another issue to the forefront: what happens when a complaint does go through? No written policy for punishing sexist or racist behaviours seems to exist. More often than not, the perpetuators are simply moved to another department, or warned without any further implication. Van Brabandt ends her remarks looking at the gender composition of the teaching body. Women or representatives of minorities are often hired with precarious contracts or invited as guests where they end up becoming diversity tokens. “Not only tokenism is disrespectful towards someone’s talent, it also places that person in a hyper visible space where one person has to represent an entire group of people based on their gender, race, sexuality and so on,” warns Pauline Salet, researcher and Gender Studies graduate.

During the conference held at the Arnhem-based cultural organisation ArtEZ Studium Generale, art teacher and philosopher Petra Van Brabandt uncovered a reality of sexism in art education. She uncovered the problematic system of ‘no complaint, no problem’. Van Brabant laments the fact that individual voices are easy to be dismissed; only collective complaints don’t pass unheard. But gathering consensus when you reside outside of the dominant group is no piece of cake. In fact, most educational institutions still rely on a prevalently white homogeneous staff and student body, making it impossible to speak up collectively. Van Brabant also brings another issue to the forefront: what happens when a complaint does go through? No written policy for punishing sexist or racist behaviours seems to exist. More often than not, the perpetuators are simply moved to another department, or warned without any further implication. Van Brabandt ends her remarks looking at the gender composition of the teaching body. Women or representatives of minorities are often hired with precarious contracts or invited as guests where they end up becoming diversity tokens. “Not only tokenism is disrespectful towards someone’s talent, it also places that person in a hyper visible space where one person has to represent an entire group of people based on their gender, race, sexuality and so on,” warns Pauline Salet, researcher and Gender Studies graduate.

“There are not enough role models for women to become artists or successful artists, because many artists are male, and this can discourage them to take that career path,” adds Astrid Kerchman, Research Assistant of Gender Studies and project coordinator at MOED (Museum of Equality and Difference). Female art students believe in being disadvantaged and undervalued compared to their male colleagues and end up feeling uncomfortable being outspoken about their work and achievements. And the reality of the art world seems to prove them right. A study conducted across 1.5 million auction house sales, showing that artworks produced by female artists usually sell for 50% less money on average as opposed to works made by men.

The male dominance over the art world

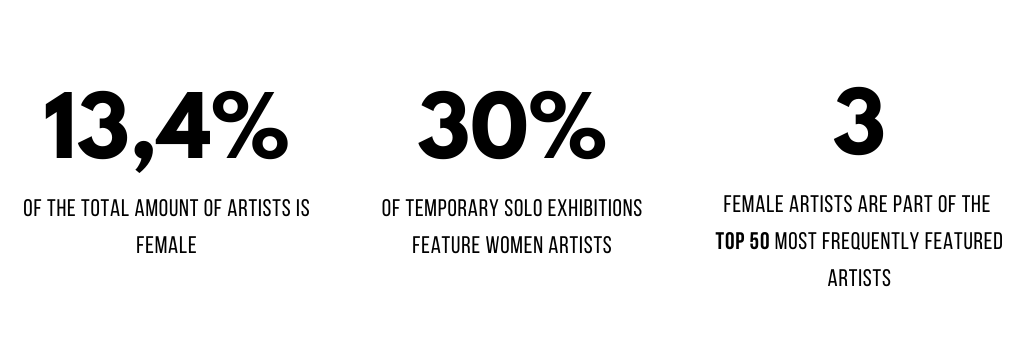

A recent report compiled for Mama Cash, an international fund supporting women’s, trans and intersex people’s movements, on eight Dutch museums – among which the Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam), the Centraal Museum (Utrecht) and the Groninger Museum (Groninger)- makes the male-dominance over the arts tangible.

The lack of representation continues in the media, as female artists receive significantly less media coverage compared to men in the sector. Women seem to make it to the front page only in disciplines commonly considered ‘feminine’ as fashion and dance, as well as for those fields of fine arts that have declined in status.

“One of the main reasons (behind women underrepresentation) is probably the way that history is written, and specifically art history,” explains Astrid Kerchman, “Western art history is very much written from a one-sided perspective, which is the perspective of the white, heterosexual male. I think what museums have done, unintentionally or intentionally, is to reproduce that canon.” There are no formally established criteria to guide museums in the art selection and acquisition process. Where the boundaries of what constitutes good art blur, the so-called ‘quality debate’ arises. On the one hand, there is widely held assumption that the artworks are chosen by museums according to their quality, which reveals itself independently of who the creator is. This position refuses to acknowledge the inherited biases that determine the concept of quality itself. As Kerchman clarifies: “The idea of what is considered as good art or who is a good artist is not neutral, and defines what is considered as good art.”

Maaike Meindertsma

“We have gotten used to labelling some artists as great and increasing the value of their work based on their position in the art canon,” continues Pauline Salet. The definition of fine or high arts privileges painting and sculpting, relegating artists who focus on crafts or other art forms to the rank of amateurs. Similarly, when thinking of ‘the artist’ most minds would picture the same image: a white cis-gender male who works alone in the light of his genius. “This translates into the acquisitions made by museums,” concludes Kerchman, “It’s easier to build upon what is already out there and what you know than to look into the gaps or what is missing or what has been erased from history.”

“It’s not that female artists weren’t there in the past, but they have often not been taken into consideration or have not been described or understood as significant or contributing,” clarifies Kerchman. Historically women have struggled to fit in the narrative of the ‘lone genius’ as there is less archival material over their biographies, or it is buried in the archives of their husbands or fathers. It is a narrative that brings the personality of the artist to the foreground, confining women to the outskirts of history, which leads aspiring female artists with a feeling of inadequacy. Maaike Meindertsma, a third-year Fine Art student at Minerva Academy, agrees: “I think there is a tendency of having the urge to explain the artist’s personal life, rather than only looking at the artworks. Sometimes it feels like you have to be special to become an artist, or to have experienced something very traumatic.”

The road towards inclusion and diversity

“Society is changing, and inclusion is really becoming part of public debate,” says Kerchman, “so they (museums) have to respond to that responsibility. They have to reflect that change.” Nevertheless, not all steps towards diversity are taken in the right direction. On International Women’s Day, the Rijksmuseum announced that artworks by three female painters (Judith Leyster, Gesina ter Borch, and Rachel Ruysch) would enter the Honor Gallery for the first time in history. “The risk with what the Rijksmuseum is doing is that you try to become inclusive by solely adding women, but the norm still remains,” warns Kerchman, “you’re not asking women to join the table for revising that idea or working through that history.” Quotas are often suggested as a solution to gender inequality not only in museums acquisitions, but at all employment levels in the art sector. As Salet argues: “Quota can be a starting point, a beginning towards reaching a goal of equal representation, but it should never be the goal.”

“Society is changing, and inclusion is really becoming part of public debate,” says Kerchman, “so they (museums) have to respond to that responsibility. They have to reflect that change.” Nevertheless, not all steps towards diversity are taken in the right direction. On International Women’s Day, the Rijksmuseum announced that artworks by three female painters (Judith Leyster, Gesina ter Borch, and Rachel Ruysch) would enter the Honor Gallery for the first time in history. “The risk with what the Rijksmuseum is doing is that you try to become inclusive by solely adding women, but the norm still remains,” warns Kerchman, “you’re not asking women to join the table for revising that idea or working through that history.” Quotas are often suggested as a solution to gender inequality not only in museums acquisitions, but at all employment levels in the art sector. As Salet argues: “Quota can be a starting point, a beginning towards reaching a goal of equal representation, but it should never be the goal.”

“I do believe that counting as a way to express inequality through numbers is a useful tool to indicate a problem, but in order to do so, many other aspects that establish an identity are neglected,” continues Salet. She is referring to the potentially problematic understanding of race, gender, and class as separate entities: “The categorisation of male versus female is a problematic one and should be used with caution, as it categorises people according to binary notions of gender, something which we try to destabilise.” Although there is no widely accepted recipe to end inequalities, a new approach is making its way through art theorists and practitioners: intersectionality. The intersectional approach points at unlearning as the first stop on the road to equality.

“I do believe that counting as a way to express inequality through numbers is a useful tool to indicate a problem, but in order to do so, many other aspects that establish an identity are neglected,” continues Salet. She is referring to the potentially problematic understanding of race, gender, and class as separate entities: “The categorisation of male versus female is a problematic one and should be used with caution, as it categorises people according to binary notions of gender, something which we try to destabilise.” Although there is no widely accepted recipe to end inequalities, a new approach is making its way through art theorists and practitioners: intersectionality. The intersectional approach points at unlearning as the first stop on the road to equality.

“Now the art world is changing,” says Kerchman with a smile. And Maaike seems to agree: “I do see a lot of female examples around me.” She recounts how her university, Minerva Academy, is consciously trying to expose its students to a more diverse staff as well as success stories from female graduates who successfully pursued a career as professional artists. Also, a growing number of grass-roots Dutch cultural organizations and art spaces are working to dismantle forms of systemic discrimination. “They really ask very different questions than museums do,” says Kerchman “and that opens many doors for incorporating women artists or artists of colour for example, by asking different questions that maybe museums are afraid to ask themselves or to engage with.”