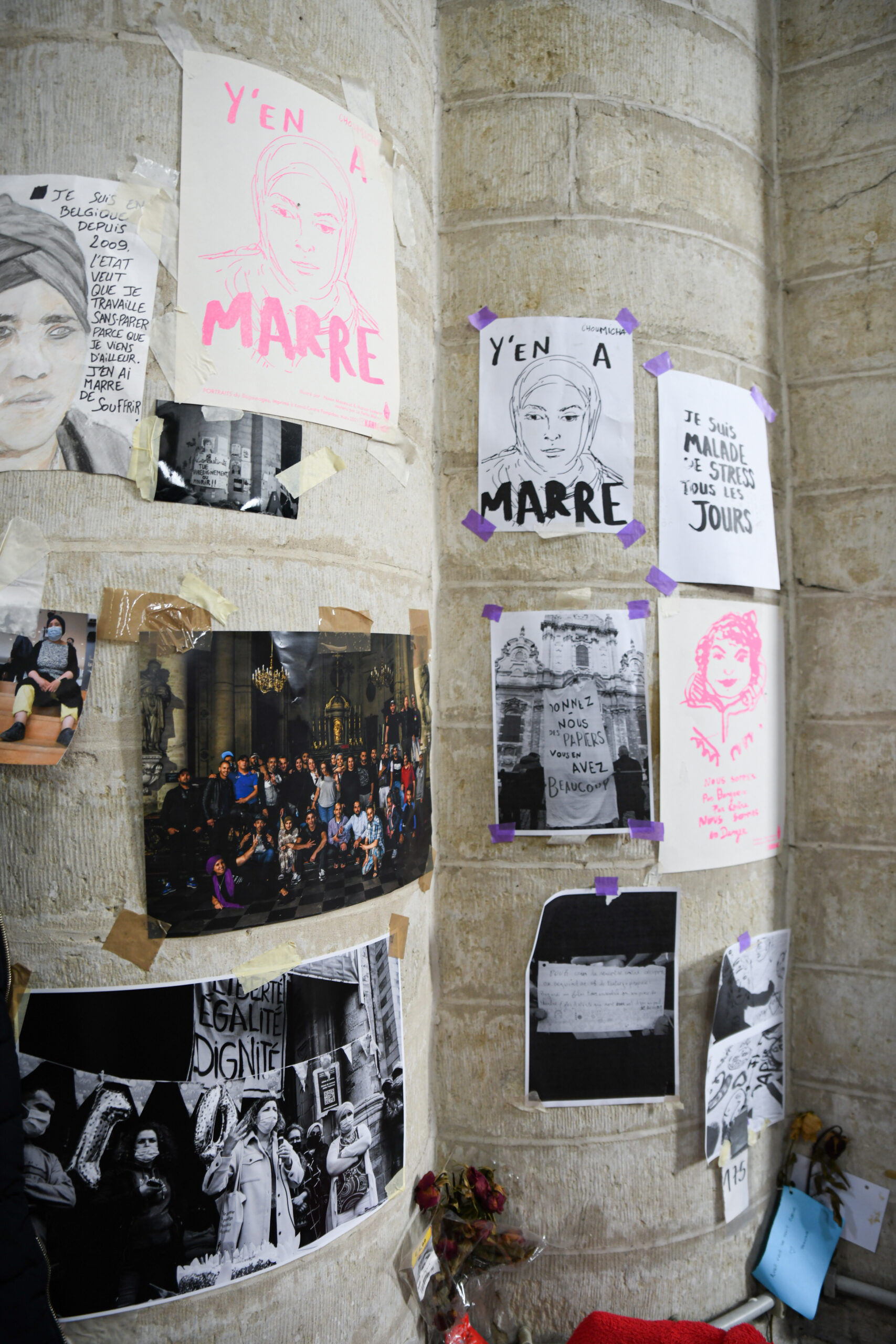

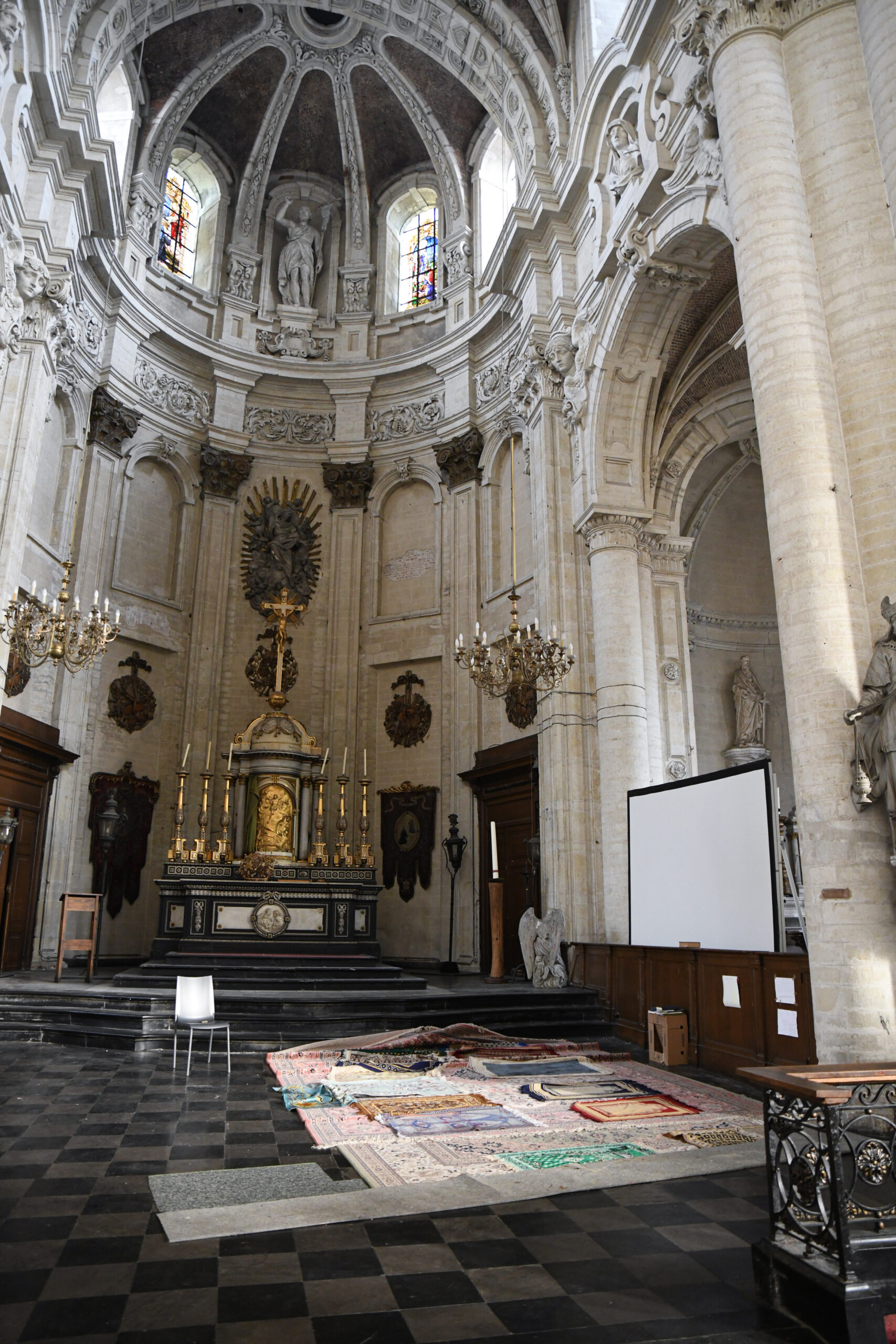

In an ancient church, about 300 years old, in downtown Brussels, you can’t find the usual rows of praying seats. Inside the St. John the Baptist church, you will find sheets hanging between pillars and walls made from cardboard. Behind these hangings sheets, you will find several improvised beds with some self-made curtain systems to give each bed some privacy to make the stay as comfortable as possible for every guest.

Of the 450 undocumented migrants now residing at 3 spots in Brussels, 100 of them are staying at the church, some have called this place home for already 11 months now. Those 11 months include 2 months of hunger strike which caused the Belgian government to review each individual case again. “This was not intended to pressure or blackmail the government, but purely because we saw no other way out”, says Mohamed, one of the Moroccan occupants. After months of waiting with high hopes, the first cases are now being denied again. Which leads the occupants to despair.

In a small, improvised living room underneath a Mary statue, tea is being poured. Mohamed asks if we would like to eat some chicken too while handing out forks. Mohamed is a young Moroccan who came to Belgium 11 years ago after completing his high school exams in Morocco. “I’ve always had family in Belgium. When I used to see them during the summer vacations, they always told me about the state of rights in Belgium and the opportunities they had in Belgium. I wanted that too.”

Mohamed and Nezha sharing lunch

After coming to Belgium Mohamed tried completing his university studies but unfortunately failed twice. “In Belgium, if you fail twice, you can’t re-study again. But you know, in 10 years, especially as a foreigner, many unexpected things can happen that can make us fail our studies. After failing my studies, I lost my residence permit and as an immigrant, that’s the end.”

“We are people who had apartments, work, friends, and family. We were fully integrated into society.” Says Nezha, who just sat down next to Mohamed to share lunch with him. “Take a good look at her. She’s our mother! Together with Sabah, she is very important for us.” says Mohamed.

“We are not homeless or refugees, most of us have been brought to work, we are an added value to this country, but the government refuses to recognize us nonetheless.” With a painful look Nezha shows the paperwork she is owning. “I am very desperate, I have all the necessary paperwork to obtain a residence permit, but the government has also rejected me”.

Nezha showing her paperwork

Together with Sabah, Nezha is one of the only women right now staying in the church. Sabah, a Moroccan occupant from Casablanca, has been staying in the church since the start of the occupancy. Throughout those months she had the responsibility of night-guard. Ensuring that no unwanted visitors enter the church at night. “An important and valuable task”, she says while showing all the blankets she uses at night to keep her warm. “However, we had to take over from her and force her to take some rest. She only slept four hours a night for months.” interrupts a neighbor of Sabah.

Sabah showing her blankets

“Momen” a Moroccan elderly man, who came to Belgium 32 years ago for work, confirmed that he had worked for a while on temporary papers, had a home and paid rent and bills, and suddenly was abandoned and could not return home after all those years to change working conditions (such as changing jobs) and the Government did not give him any identification papers that would give him his rights like everyone else.

Cécile de Blic, a French woman that volunteers in the church, is visiting the occupants several times a week to see how they are doing.

According to Cécile, there are 450 protesters at 3 different places in Brussels. One of which is the Church of John the Baptist, which was chosen by the protesters because it is no longer a church where rituals have been held for two years. The monk in charge, the 77-year-old Daniel Allitt, is helping the needy occupants by taking an active social role.

“There were several economic agreements between Belgium and Morocco a long time ago, after which Moroccan workers were brought to Belgium.” Says Cécile. “But unfortunately when their work is done, they are not granted any rights. Like Momen for example, they were simply seen as a threat.”

https://soundcloud.com/simon-ruisch/cecile-de-blic_2

“I am a French citizen and I moved to Belgium 12 years ago. Because I am white and carrying a French passport, I have not had any problem and I have not felt any difference all that time, but immigrants of other nationalities such as these protesters suffer daily because of their nationalities and the way Belgium sees them.”

“Look at Nezha for example. She has all the paperwork she needs to get a permit of residence. And her case has been reviewed, and simply been refused again.”

https://soundcloud.com/simon-ruisch/cecile-de-blic

“Despite the government’s promises, our hunger strike did not turn out to be a success” Says Momen. “We started our occupancy in January 2021, but because we were desperate and simply nothing happened, we went on hunger strike from May 23 to July 21. Together with 455 people in the three different places.” “After 5 days, we moved from a hunger strike to a drinking strike. The government gave us many promises, so we stopped the hunger and drinking strike and returned to hope again.”

“We all were rejected, we don’t know why despite all those promises? We don’t know what to do right now”. Cécile confirms what Momen says: “The truth is that we do not know why the Belgium government broke its many promises that it had given to them. Only last week, a decision was sent to everyone after three months waiting with high hopes.”

“We are here again, and although our files have been rejected and we have had high hopes, but we continue to fight again, there is always hope, we need to keep hope”, says Mohamed. “You know the worst thing, I think, is that the media is saying about us: these people are going on hunger strike to pressure the government and blackmail them. But that wasn’t our goal, the hunger strike simply showed our anger because we’re hopeless, that was the only reason,”

Local media also describe undocumented immigrants as “illegal immigrants”, and local newspapers in Belgium also confirmed that the immigration policy of successive governments was characterized by ignored unregulated workers, estimated at 150,000.

“Unfortunately, the problem of organizing immigrant papers is not a priority for the government because it is a vulnerable group that has no voice, not even for political parties that are now interested in preparing for the next election,” says Cécile

According to her, many of the occupants sacrificed a lot during their stay. Many of them lost their jobs, some lost their homes and most of them have family in the country of origin that are worried about them. All those worries have now been for nothing since the government again refused their cases.

https://soundcloud.com/simon-ruisch/cecile-de-blic_3

“What do we do now? We live day by day.”, says Momen. “The most important thing for most people here is to find a job. The job is the first thing we need to get an independent life, but we need paperwork to find a job.”, says Mohamed.

Momen in his ‘room’

Seeking employment is the biggest obstacle faced by these protesters, although Belgian law, according to the local press, grants undocumented immigrants full integration into Belgian society from marriage, family formation, and schooling of their children, at the same time the necessary social and health protection is not provided, which does not enable them to work in decent conditions.

Because of the lack of paperwork, they cannot work officially, which leads employers to exploit them by giving them salaries below the minimum wage with working hours that exceed the legal rate and without health insurance, in addition to many of the rights they have been denied, all of which have been exacerbated by the Corona epidemic crisis.