It is always hard to find a sense of collective identity in big cities, a feeling of belonging in the middle of endless streets and crowded spaces. And Berlin is not an exception. Boundaries have often been built in the so-called “city of freedom” and since the fall of the Wall in 189 and the upcoming reunification, there have been several cultural politics to find a sense of identity for Berlin and a contested collective memory. However, according to the historian and writer of the book “At the Edge of the Wall: Public and Private Spheres in Divided Berlin”, Dr. Hanno Hochmuth, Berlin has always been a polycentric city with different identities.

The city consists of former villages that were merged almost a hundred years ago. According to Hochmuth, this Kiez or neighborhood identity is also due to the urbanistic composition of the city: “The city has several city centers, not one, but at least two or three. So, people tend to develop their identity with their own neighborhoods”, explains. However, these identities are in constant change, just as the city and the people living in it develop.

An example of this feeling of community and incessant growth of the city are the districts of Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg. Despite sharing a very similar proletarian past, both neighborhoods had apparently grown apart. During the political division of Berlin during the Cold War, the two neighborhoods remained separated by the Wall, following different political and social paths until 2001, when they were merged into a common administrative district.

- tourists looking to Kreuzberg

- Oberbaum bridge

Like temporally separated twins, Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg started to experiment grand differences that still remain today. Kreuzberg, situated in the west part of the city, was pushed away to the periphery when the Wall was constructed. This made the neighborhood appealing to young and immigrant residents, but also placed the district at the end of West Berlin’s poverty scale. Out of the political changes of the 70s and the 80s, a particular Kreuzberg identity based in multi-ethnicity and alternative scenes emerges. Kiez is no longer an insult, but a positive term. The idea of the neighborhood is also rediscovered in Friedrichshain with a scene that questioned the East German way of life.

The ghost of gentrification

Today, both districts united again, are seen as popular neighborhoods that welcome migrant families and attract tourists in search of the alternative charm of the city. Cosmopolitan, tolerant, and creative. But also gentrified and marketable. Multiple tourists can be seen walking through Oranienstraße street or taking photos of the street art. Roberto Fernández a Spanish tourist guide living in Berlin claims to have done more than two tours a day through the alternative neighborhood. “I have seen how these districts have changed during the past years, you can see the interest of bigger entities in them”, explains.

- Tourist looking at Victor Ash’s Astronaut Cosmonaut

Berlin touristic boom also have had serious consequences for Kreuzberg and Freiedrichshain urban structures. According to the archive of the FHXB Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Museum, from 2006 to 2014 the number of overnight guests in the district growled from 1.8 to 3.8 million per year. In the summer of 2014, 960 vacation apartments are registered across the district; the unreported number is estimated to be twice as high. As vacation rentals are kept off the regular housing market, the housing shortage intensifies, and rents increase at an alarming rate. Dr. Hochmuth points out the consequences of these process of gentrification in the neighborhoods: “The urban renewal it is usually a huge demographic change and a replacement of poor people by young urban elites”.

Tourism also changed the commercial structure of the neighborhood around Oraienstrasse. A wide variery of clothing boutiques, cafés and food establishments are spreading out as the local population’s daily needs became subordinate to the preferences of the temporary guests. The change of traditional to hipster bars or having to order a in English instead of German as details that made neighbors not feeling at home anymore. “It is not always the simple reason that they can’t afford the rent anymore, but it’s also sometimes thar they cannot get along with the cultural change of the district”, explains Hochmuth.

The first victims of gentrification are people with migrant backgrounds, which have a significant representation of the district. Mostly Turkish population have lived in Kreuzberg since the 1960s. But according to Dr.Hochmuth, nowadays they are being forced to leave the neighborhood and move to other areas of the city. Consequently, districts than ten years where homogeneous, appear to be more multicultural than they used to be.

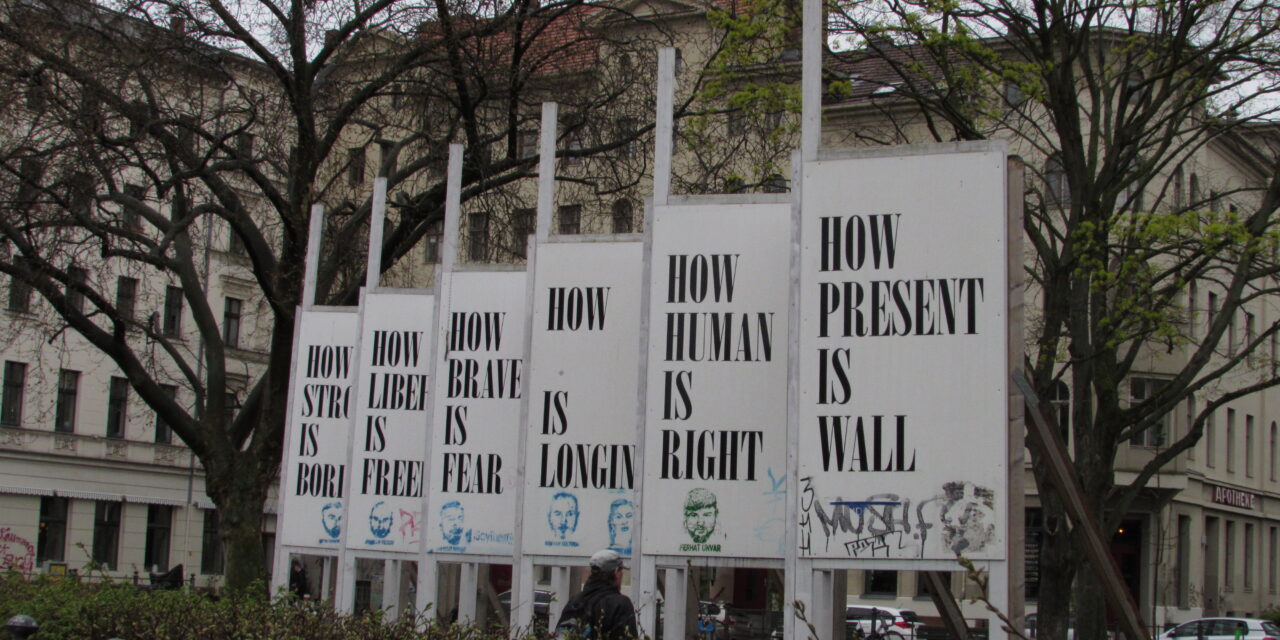

These neighborhoods have also been the place for many artistic and squatter movements in the past decades that today struggle to make a living in Berlin. The independent art and diverse sub-cultural scenes that provided Berlin the status of “Creative City” since reunification are now at risk of not being part of the city’s future. Due to massive real state investments in this district, the public sale of properties and the high inward migration the cost of living has risen in Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg and there are less suitable spaces for artistic work and performances available. “Creative cultural spaces in this district are under pressure as they don’t have long term contraction”, claims Dr.Hochmuth.

- Skatehall in RAW Space

- RAW

- RAW

- RAW

To whom will the district belong?

Today in Friedrichain-Kreuzberg business and tourism overlaps with poverty and working-class people. Social contrasts are evident in the district, and something might be lost with the displacement of the low-income members of the local population that paradoxically made the neighborhood attractive. As Berlin is a city of constant changing is difficult to tell whom does the district belong. The only certainty as Hochmuth claims is that gentrification has not yet come to an end in Friedrichain-Kreuzberg.