Everyone is aware of the reports on the situation of press freedom in Poland and Hungary, which has deteriorated rapidly in recent years. But if you look eastward, you will notice that one country has had a particularly bad press freedom situation for decades, but has received less media attention. That country is Bulgaria.

The annual Reporters Without Borders (RWB) report on the state of press freedom finds that information diversity and investigative journalism are under serious threat in Bulgaria. In 2021, the southeastern European country ranked 112th out of 180 in the world. In 2009, two years after Bulgaria’s entry into the EU, RWB already reported that press freedom in the country was endangered. However, at that time Bulgaria was ranked 59th, and today it is far from that rank. RWB started to publish the press freedom index in 2002. Back then, Bulgaria has been an EU membership candidate and was even ranked 38th. How did this development come about? Will the situation change with the new government that was elected last November, or has it already?

This data is based on the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index 2021. (Editor: Annika Karoline Schleithoff)

Political turbulences

Explanations for these strong changes can be found, among others, in the country’s political situation. Since the end of communism with the fall of the Iron Curtain and the Eastern Bloc countries in 1989, the country has been a parliamentary democracy. With few exceptions, the conservative GERB party nominated Boyko Borisov as prime minister until April 2021. After that, the party landscape fragmented, making it difficult to form a government. As a result, three parliamentary elections were held in 2021. In the last election on Nov. 14, 2021, the duo of Kiril Petkov and Assen Vassilev won with their newly formed party “We Continue the Change” (PP). The new coalition consists of four parties led by the PP party and has set itself the goal of reforming the judiciary and fighting corruption, among other things. In addition, an economic recovery is to be initiated. If all this succeeds, it would also be a benefit for press freedom.

This raises hope among many people, and expectations for change are rising. “Expectations, however, do not mean that things will actually happen. The government has set some good directions, but whether and how they will actually work out in reality remains to be seen”, says Christopher Resch of Reporters Without Borders.

It is true that just a few months after the start of the new government’s work, it can be seen that Bulgaria has now risen to 91st place in the world rankings for press freedom (this is the current status, the evaluation for 2022 will not be published until 2023). But Bulgaria still ranks among the three worst EU countries.

Threats to press freedom

Reporters Without Borders identifies a total of three major areas of concern in Bulgaria that are having a major impact on press freedom in the country. “There are three main issues that we observe and these are non-transparent funding, defamation and hatred, and impunity,” says Christopher Resch of Reporters Without Borders.

Economic foundations for media are very important, but there has been a very non-transparent distribution of EU funds and state funds in recent years, he said. “This happened mainly through advertising profits in newspapers and on television, because when the state advertises a lot and focuses on certain favourable media, it has a very big influence,” says Christopher Resch. In addition, during Borisov’s three terms as prime minister since 2009, important national media in Bulgaria have been sold to businessmen close to him. According to RWB, the few entrepreneurs who own a large part of the Bulgarian media determine the editorial line in close coordination with leading politicians.

Bulgaria’s decline down the world press freedom rankings began with the founding of the New Bulgarian Media Group 15 years ago. The New Media Group, controlled by MRF MP Delyan Peevski (part of Renew Europe in the EU Parliament), “started buying media aggressively”, according to Krasen Nikolov, a journalist at the independent news website Mediapool.bg.

Delyan Peevski is the man who now owns numerous Bulgarian media companies, from various newspapers to television stations and websites. In addition, Peevski and his companies are also among the largest advertisers in the Bulgarian advertising market, where orders are distributed in a non-transparent manner. He was sanctioned by the U.S. Magnitsky Act in June 2021 for “substantial corruption”.

“Around Peevski’s media there was an even larger circle of media that formally belonged to others but closely followed Peevski’s media policy. These media still exist”, Nikolov says. Peevski’s media group supported Borisov’s governments, created lists of enemies of the government, and media critical of the government were accused of spreading “fake news.” Since fall 2020, the media group is owned by United Group. “Thus, the Bulgarian media market lost its ugliest face”, says Krasen Nikolov.

Bulgaria remains one of the poorest countries in the EU. The contrast between rich and poor is also visible in parts of the city. (Photo: Annika Karoline Schleithoff)

Years after joining the EU, corruption, organized crime, social inequality and poverty are still major problems in Bulgaria. Bulgaria is considered the poorest and most corrupt country in the EU.

In some cases, EU funds even contributed to an increase in corruption, as funds went to the government in an uncontrolled manner and were distributed in a non-transparent way. Former Prime Minister Borisov was arrested in March this year on suspicion of misusing EU funds. However, he was released after 24 hours. Moreover, it was said that they are now investigating not on suspicion of misuse of EU funds, but on suspicion of extortion. The EU prosecutor’s office is therefore no longer part of the proceedings.

Years after joining the EU, corruption, organized crime, social inequality and poverty are still major problems in Bulgaria (Photo: Annika Karoline Schleithoff)

The role of the judicial system

In addition to corruption and non-transparent media financing processes in Bulgaria, there are other problems that make the work of journalists difficult. According to RWB, there has been a decrease in physical attacks on journalists in recent years (ranking in the security category: 60). However, it is dangerous to report on crime, especially corruption and organized crime, the latter of which is dangerous in any country in the world. Instead, smear campaigns and hate and incitement are the order of the day in Bulgaria. Journalists who are affected by hatred and death threats and report them can hope for little help. Often, the reports are not pursued at all.

This highlights the third problem area: impunity. People who spread threats and incitement do not have to expect to be prosecuted. The government is supposed to protect citizens, but instead, it often encourages hate campaigns instead of intervening, says Barbara Erbe of Amnesty International. “These hate campaigns scare off many journalists and then many remain silent, only the brave continue to speak out”, says Resch. There is a name for these deterrent effects: SLAPPs. The name stands for “strategic lawsuit against public participation”. They are used specifically to intimidate and silence journalists by burdening them with the costs of the legal process. “This strategy is used by large corporations and also by politicians”, says Christopher Resch.

This is also confirmed by journalist Krasen Nikolov. In the last two to three years, he says, SLAPPs have been a big problem in Bulgaria. Mediapool.bg, the news website Nikolov works for, is being sued for 30,000 euros because of articles that – according to the accusation – had slandered the then president of a Sofia court, Svetlin Michailov. “The unreformed judiciary only intensifies this problem”, says Nikolov.

The bad state of press freedom is no secret among the population. “People know what is happening and they know how bad the situation of press freedom and corruption is”, says Martin Getov. He is a student from Sofia and is currently studying in the Netherlands. “There are three main tv media and they are owned by shady people”, he says. The biggest media and TV channels are owned by a small group of people and for them, it is better to take the government’s point of view and act pro-government. For example, if their opinion during the Covid pandemic was against vaccines, not a single person was invited for an interview who was positioned pro-vaccine. Martin Getov did an internship at Spisanie 8 in Sofia, a magazine for popular science, where he was able to learn more about the processes and the difficulties in the industry. “People lose their jobs if they have the ‘wrong’ opinion and some say: don’t speak about this”, he says.

Especially for journalists working independently, the conditions became worse within the last years. (Photo: Annika Karoline Schleithoff)

Social media as a new platform

Due to the difficult financing situation for independent journalism, the importance of social media as a form of journalistic distribution is growing. If journalists who report independently cannot find customers or advertisers with whom they can finance their work, they can at least reach a young and large public on social media. But even there, financing remains difficult.

Because people in Bulgaria know how bad the freedom of the press is in the country and therefore the trust in the media information is not high, many people have not been consuming news for years, especially TV news, says Martin Getov. He himself reads online news sites, but not only Bulgarian ones, but also English and Russian ones, to be able to compare as many viewpoints and perspectives as possible. “People want to be informed and at least the young people try to get their info from all kinds of places and this is how they see how much censorship there is”, he says. Many young people follow the news situation mainly on the Internet, on news sites of international newspapers, Instagram and Facebook pages of journalists and politicians.

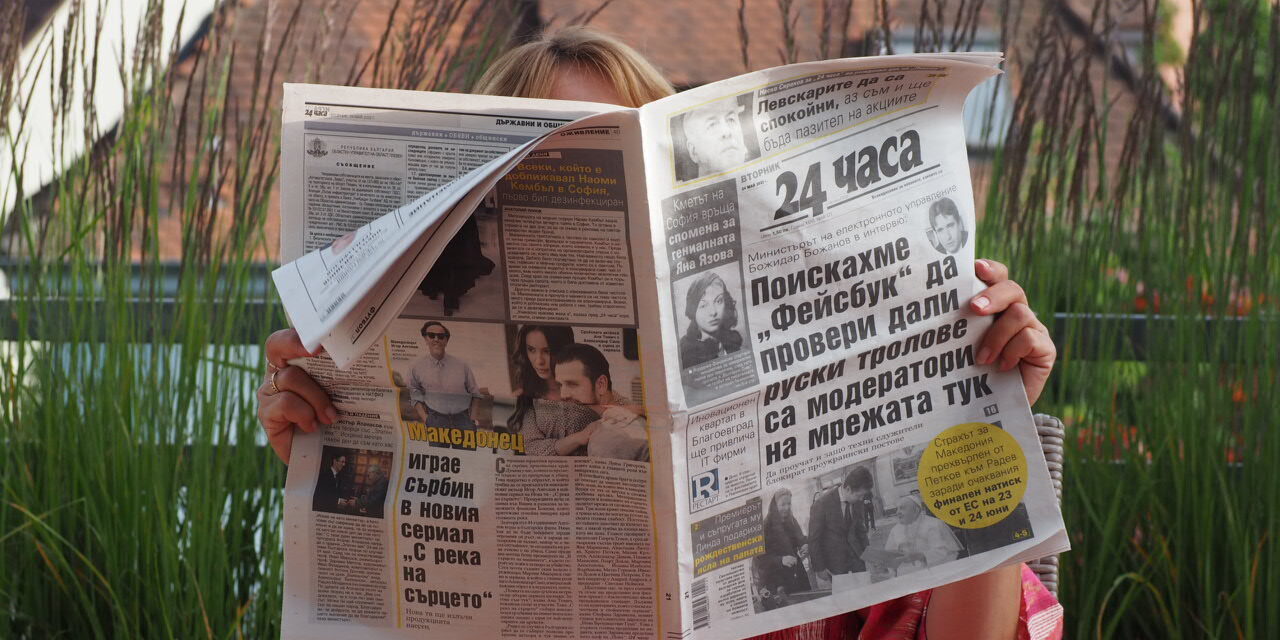

When I travelled to Sofia to research the situation of press freedom on the spot, I did not see anyone buying a newspaper. As I asked the employee in a kiosk which newspaper she could recommend to me and which one she considered the best, she couldn’t or wouldn’t tell me.

Mitko (name changed by the editor) also consumes very little Bulgarian news. “It is also known that certain media are sponsored by certain political parties”, says the Bulgarian student from Plovdiv. As a result, he says, one can expect that the interests are supported by the party and that certain information is hidden or reinterpreted to suit them. He also says that a large part of the news can be summarized as something happened somewhere and details are often missing. When these later become clear, one notices that the situation was intentionally presented worse, so that more people click on reports about it.

Why is independent journalism that important?

Reporters Without Borders considers information to be the first step toward change. That is why authoritarian governments fear independent and free reporting. Freedom of the press is the basis of a democratic society. RWB refers to Article 19 of the UN Declaration of Universal Human Rights, which states that everyone has the right to freedom of expression, including the right to hold opinions and to have the opinions of others heard. Article 19 thus prohibits state censorship. Moreover, quality journalism is the best means against disinformation. “People must be allowed to express their opinions freely for there to be anything like a democratic discourse”, says Barbara Erbe of Amnesty International.

The daily newspaper Sega, which is based in this building, claims to be politically independent. Sascho Donchev is the founder and publisher and, together with Gazprom, holds a stake in the Bulgarian gas company Overgas. (Foto: Annika Karoline Schleithoff)

For years, many Bulgarians have hardly consumed the traditional media, but instead, use social media and online news to inform themselves (Photo: Annika Karoline Schleithoff)

Independent journalists in Bulgaria

But the brave are not silent. The brave continue to speak. Despite all the deterrent effects and threats, there are independent journalists who continue their work and do not let themselves be silenced, even if this – as described – attracts SLAPPs to them.

Mediapool.bg belongs to the group of the brave. Founded in 2000, by a group of independent journalists, it is the first Bulgarian daily published information-analytical website on the Internet. Mediapool.bg claims to be an independent media defending only the public interest and offering information that meets the highest journalistic standards. RWB confirm the independence of Mediapool.bg, also in connection with the SLAPPs from last year.

The Palace of Justice in Sofia. Repeatedly, Bulgarian journalists become victims of so-called “strategic lawsuit against public participation” (SLAPPs) (Photo: Annika Karoline Schleithoff)

Krasen Nikolov has worked as a journalist at Mediapool.bg for 17 years and has been editor-in-chief of the Bulgarian office of the news website EURACTIV for three years. Unlike other Bulgarian media, “there is no censorship in these two media”, says Nikolov. However, the main problem remains insufficient funding. As a result, there are few well-trained journalists, few journalists, therefore, have to cover many topics, and salaries are extremely low. “This often results in journalists not having enough time and financial resources to invest in in-depth research”, Nikolov says.

The fall of the GERB government last year lifted heavy pressure on the media from the state, but there is still concern that the situation is unstable, he says. Above all, the lack of financial revenue makes most media companies dependent on corporate and government pressure. Mediapool.bg is financed more as a non-governmental organization with long-term projects and grants, he says.

“Mediapool.bg is one of the Bulgarian media that can be proud of its investigative journalism and in-depth articles,” says Krasen Nikolov. Hopefully, the new government will realize its intentions so that the situation in the media sector and freedom of the press will also steadily improve again. Because not only is freedom of the press the basis for a democratic society, if independent reporting is not allowed, it is also an indicator that other human rights are being violated.

Note: The Press Freedom Index

Reporters Without Borders annually publishes the Press Freedom Index, a ranking of all countries worldwide. The ranking is done through interviews with journalists in the field and also through quantitative measurements. The questionnaire includes 123 questions divided into five different categories. The categories cover the political, legal, economic and socio-cultural context as well as the security factor. For example, the questionnaire examines whether there is a legal situation that allows journalists to work freely and, in the best case, protects their rights, or whether politicians exert targeted influence on reporting.

(Source: Reporters Without Borders, 2022)

Follow this link to see a Reporters Without Borders world map with current developments and rankings https://rsf.org/en/index