The entrance fee is average, the price of beer acceptable, yet it looks like an exclusive upper-class club. Noble interior in dark and gold colours, fancy shirts, sleek hair-do, glamorous yet revealing dresses, high-heels, jewellery. In Club Biad they play Chalga, a controversial Bulgarian variant of pop-folk upon which the population is divided. Is it a bane of Bulgarian culture, promoting loose morals, irresponsible promiscuity and materialism? Or an expression of deep human desires and heartaches, a sound to finally let go to? I’m here to investigate. And all around everyone’s dancing or clapping their hands to the beat of a love song I do not understand.

Chalga came up in around ‘89 and was forbidden under the socialist regime. The incorporation of other Balkan countries’, Arabic, Turkish, and Gypsy musical traditions didn’t go well with the ruling party’s vision of a mono-ethnic state. Not to speak of the lyrics dealing with sex, drugs and corruption. All against socialist morals. So in the early years those things that may seem superficial or hedonistic about Chalga now symbolized a newly found freedom. For example having your own business and making lots of money or wearing scarce clothes without being chased by the police simply weren’t possible before. This explains the Chalga tradition of showering the dance floor with napkins, throwing them in the air like you’d imagine a crazy millionaire doing it with money.

Throughout the 90s and early 2000s Chalga remained a genre in which boundaries are overstepped. In 1999 Azis, probably the most famous Chalga singer, dropped his first album. He is openly homosexual and for a long time displayed a lasciviously flamboyant, cross-dresseresque image to the public. Keep in mind that this happened in a to this day very conservative eastern European society. Check out one of his music videos to get an idea of his art.

Enlarge

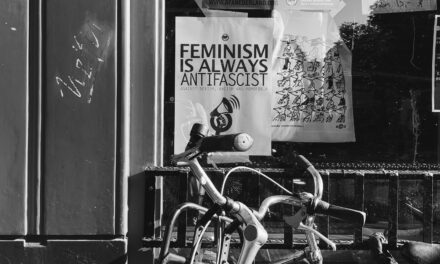

From what I’ve been told modern Chalga is more provocative then ever. Though not in a political or socially conscious way any more. What provokes the old and the conservative, the squares nowadays is the more and more rampant and explicit display of the sex, drugs, partying lifestyle. That this goes against traditional family values is obvious. And it’s not exactly the feminist type of liberated sexuality either. More the “I’m gonna steal your boyfriend/girlfriend” and “I’m making lots of money and fucking lots of [insert derogatory for women]” type.

Most foreigners won’t have a clue how huge Chalga is in Bulgaria. There are multible big clubs dedicated to it in the capital. In parks near those venues you’ll see big groups gathering by around eight or nine pm, having pre-drinks. All of them are fans. According to a poll by nonivite.com 48% of Bulgarians like Chalga and 41% disklike it. One thing I’ve been repeatedly told is that way more people listen to Chalga than you’d assume. It’s just that a lot of people do it in secret because of it’s reputation as a low form of art.

The first thing I noticed while talking to the locals is that they are quite opinionated on this subject, though not necessarily free of ambiguity. “The people who life this lifestyle have nothing else in their lives. They work their nine to five jobs, not making a lot of money, then for the Chalga parties they dress up like they’re rich and only care about partying. They are empty people who only want pleasure in the moment”, says the guy selling me fast-food. He proceeds: “I really enjoy it myself when I’m buzzed on a few drinks.”

Anyway, to find a proper source I went to Club Biad, which I’d been told is popular hangout place for Chalga musicians. Asking around I actually manage to locate one. An average looking guy, mid to late thirties, smoking hookah in the niche between the bar and the small platform on which the hired dancer is shaking it in thong and bra. At first his bodyguard, maybe taking me for an overly eager fan, doesn’t let me into the niche. Typing what I want to say into my phone’s notepad and having the sympathetically amused waitress translating I finally get to talk to the agent and we schedule an interview. Just in time for me to witness my first napkin shower.

Enlarge

Ceco was a rapper for six or seven years before he became a Chalga singer. He says there is more freedom of expression in Chalga. The accusations of the genre promoting loose morals are simply wrong to him. “We live in the 21st century. Everybody is more open to sexuality. It’s normal in our time.” Generally most of the things he has to say seem to revolve around the freedom part. When asked about changes in the topics Chalga is dealing with: “There is freedom in Chalga. You can criticise, say whatever you want to say, no one’s gonna be offended because it’s Chalga. Nowadays people don’t think it’s important to criticise the system in music.” Or about the attitude towards women it promotes: “There’s freedom, everyone understands life in different ways. True, in Chalga they sing more for love, more for men with money. Everyone understands different men treat women differently. Especially I treat women with flowers and with love. There’s other kinds of men who treat women badly. Again it’s freedom everyone can say what they want to say. It’s not specified in Chalga how a man will treat a woman. Everyone’s free, whatever they want to say.”

Enlarge

The Bulgarian ethnomusicologist Prof. DSc Ventislav takes a more critical stance. He says the culture surrounding Chalga glorifies what he calls the “newly-found heroes of our time”. Heroes within a “confused system of values”, he emphasizes, their heroicness being the display of “materialist signs of capitalist prosperity”. He is deeply worried about the meaning of such role-models. “If you’re born after 1990 and from a young age listened to Chalga’s dirty fairy-tales, you may mistake them with reality.”

I do not have the best feeling about ending the article on such a negative note. After all I’m just some Westerner doing research on a foreign culture. And I had fun visiting Chalga venues, found the people very easygoing to talk to. Maybe before coming to any sort of judgement one should consider what Ceco told me at the end of our interview (that had been entirely translated by his agent by the way): “The audience of Chalga is more a Balkan audience. They’re more open at parties and know how to have fun.” Who knows?