“Belgium saved me. Before I came to Brussels, I was constantly in self-preservation mode” – says Georgian transgender Katalina Jorjeuli (37) on an outside terrace – enjoying the sun. The number of Georgian refugees in Belgium has doubled since the Georgian government has intensified its nationalism and discrimination, particularly against the LGBTQ+ community. According to the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons(CGRS), Georgia ranks eighth among the top countries whose residents applied for asylum in Belgium as of March 2024, with 79 applicants in that month alone.

“I am thankful for this country. I do not think I could ever repay Belgium for what it has done for me. I am safe and alive now”

– mentions Georgian queer man Lukas Ablotia (19), who has been out of the closet for three years now, reaching for his cup of coffee, covering his face from the sun.

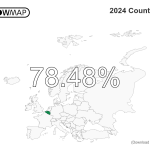

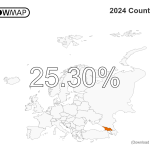

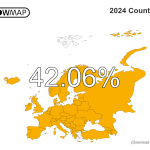

“Everything here is different. I am not afraid. This is where they take me as I am.” Recalling the times Jorjeuli had to remind society that she could express herself as she wished, she mentions, “Here they ask me who I am, not what my parents named me. I am Kato, and I am a woman.” According to Rainbow house’s data map, Belgium has a human rights and equality index of 78%, which sets the country on the top three countries list, while Georgia scores only 25%, with a place of 36 out of 48.

- Belgium

- Georgia

- Europe

Katalina Jorjeuli and Lukas Ablotia are friends, as they both moved to Brussels less than a year ago. Walking through Brussels on the so-called gay street [Kolenmarkt], pointing at every pride flag and telling stories of gay bars and Belgian Smurfs, Katalina mentions,

"It took time, but here I am still who I was, just the best version of myself."

Jorjeuli served in the military for 16 years before coming out. She talks about her different life here. She is now just Kato (a nickname she uses), with no one asking about her dead [male] name. She feels free to color her nails and plans to buy high-heeled shoes to practice walking in thin heels. “Those would not be my worries back home. I could not take it anymore; I was so suffocated I couldn’t even take public transportation for fear of being assaulted,” Katalina explains while holding a leather clutch, something she would not even think about in Georgia, as it would mean stares and in many cases, violence. As for Lukas Ablotia, who has been out for three years now, taking public transportation in Georgia ended up with an older man assaulting him on the bus for the “feminine” way Lukas was dressed.

The research “Human Rights Violations Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Georgia” shows the pervasive violence against the LGBTQ+ community in Georgia is both public and private, with a 2018 study revealing that 88.3% of respondents experienced hate crimes since 2015, including psychological, sexual, and physical abuse. Yet, only 16.8% reported these incidents due to fear of outing, re-victimization, and distrust in law enforcement.

Expression is a striking feature of Brussels, with its abundance of rainbow colours—flags, crosswalks, stickers, and souvenirs all adorned with vibrant rainbow schemes.

Georgia’s Removal from Safe Countries List

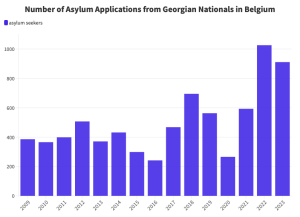

In 2023, Belgium removed Georgia from its list of safe countries. According to the European Council on Refugees and Exiles, data from 2023 reveals a notable disparity; a significant proportion of asylum applications in Belgium were from Georgia, distinguishing it from other nations still considered safe. According to the same council, a country is considered safe if its democratic system and political conditions generally protect against persecution or serious harm and ensure respect for fundamental rights. Because of this, the asylum process is smoother than for countries considered “safe.”

Meanwhile, Georgians protest the ‘foreign agents’ bill, which mandates NGOs and media outlets with over 20% of their funding from abroad to register as entities pursuing the interests of a foreign power. According to the Venice Commission, this law has significant negative consequences for the freedoms of association, expression, privacy, participation in public affairs, and the prohibition of discrimination.

A study by UCLA School of Law on the social acceptance of LGBTI people from 1981 to 2020 ranked Georgia 141 out of 175 countries, behind nations such as Niger, Sudan, and Morocco. While belgium is set on 15th place, in front of countries like France and Germany. Most importantly, data from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) survey shows that Georgia is the most homophobic country in Europe as of 2021, with 84% of Georgians thinking that sexual relations between two adults of the same sex are always wrong.

Anti-LGBTQ+ Propaganda Law

The Georgian government is attempting to implement an anti-LGBTQ+ law, clamping down on LGBTQ+ rights and barring public celebrations of same-sex relationships. Chairman of the ruling party, Irakli Garibashvili, made a statement on March 2nd, following a meeting with party organisations: “More than 90% of our people feel that it is essential to protect our children, grandchildren, and the younger generation from this harmful, anti-national, and anti-human propaganda.” Garibashvili calls this “a widespread campaign, an intensified propaganda,” mentioning how “in European kindergartens and schools, they bring in transgender individuals, show them to the children, and tell them that if they don’t like their gender, they can change it.”

The same law has been active in Russia and, as of 2021, in Hungary too. Hungary’s LGBTQ+ law has led to increased censorship, such as the restriction of certain photographs and the plastic wrapping of books with LGBT content. While the Georgian government uses hate speech and homophobia to try to implement the anti-LGBTQ propaganda law, the Georgian queer community lives in fear that the outcome of this law will be just like Hungary’s for them.

an article from Radio Tavisupleba discusses a new legislative initiative by the “Georgian Dream” party to restrict LGBTQ+ rights in Georgia. It outlines several proposed changes, including prohibiting the recognition of any relationship forms other than traditional marriages, preventing adoptions by individuals who identify as a different gender or are not heterosexual, and restricting changes to gender identity in official documents. The proposal also aims to ban “propaganda” of non-traditional sexual relationships within educational settings and the media.

Katalina Jorjeuli says:

"They want to hide us, as if we do not exist, but we are here."

The queer community in Georgia has not only persevered but has also created significant safe spaces. “I love my country; I did not want to leave my home, but it was the only option,” Lukas Ablotia adds, sharing his journey of moving to Belgium to escape societal hatred and oppressive government policies.

While reminiscing over photos of life back in Tbilisi, Lukas and Katalina talk about their nostalgia and love for their country and the legal and safety reasons that prevent their return for five years. They express their efforts to make Brussels feel like a second home. “I want my mom to see this place; she would love it,” says Katalina. Moving away from their homeland was fraught with challenges, yet for these Georgian queers, it was an inevitable choice.

From Tbilisi Pride Violence to Colourful Streets of Brussels

On May 17th, Georgia celebrates Family Purity Day, while most European cities, including Brussels, celebrate Pride with rainbow-colored buses, glittery faces, and techno music. the federal action plan “For a LGBTQI+ Friendly Belgium” led by State Secretary Sarah Schlitz 133 measures across various federal policy domains aimed at strengthening the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex citizens. operating within the EU and globally to systematically enhance LGBTQ+ safety and promote their full inclusion. And with this year’s pride message: ‘No one left behind’, For the first time, Katalina Jorjeuli and Lukas Ablotia participated in Pride without experiencing violence.

“it is amazing, the sense of community you get watching all these people together” – says Jorjeuli, smiling looking at the poster of Brussels pride. Julia Kundler, a legal adviser for the Rainbow Refugee Committee, the association aims to support people who base their application for international protection on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity, calls this “the lost in translation experience”. With in the see of people raised Georgian flag the Pride festivals Massage [no one left behind] really feels alive.

In contrast, Tbilisi Pride struggles to create a safe environment for its events, often facing danger and insecurity. In 2023, a Pride festival ended with the burning of pride flags by right-wing protesters. A similar incident happened in 2021 when far-right activists attacked the office of Tbilisi Pride in Georgia’s capital, Tbilisi. Waving a Georgian flag among rainbow-colored flags meant a lot to Lukas. He shares that the 2023 Tbilisi Pride event was the moment he had to leave Georgia to survive.

“What I saw on that day, the hatred, the unsafeness I felt, I knew I could no longer be protected by anyone, even law,”says Ablotia.

Both Katalina and Lukas are activists who were deeply involved in protests back in Georgia. “Activism isn’t just personal; it’s about advocating for the entire community,” explains Lukas Ablotia. Their fight extends beyond individual rights, encompassing broader political and social implications. “I had to leave my country for the love of freedom,” says Lukas, who has continued his activism in Brussels. Known as the capital of the European Union, Brussels has hosted numerous protests with both Katalina Jorjeuli and Lukas Ablotia actively participating. Together, they have proudly waved Georgian, Pride, and European Union flags, symbolising their intertwined struggles and hopes.

Barriers in Georgia for the Queer Community

Katalina Jorjeuli shares her story of being homeless for ten days and living in a queer shelter for three months. She says she found what she was looking for in Brussels:

“boldness, openness, and acceptance.”

After coming out, Katalina was unemployed for a year in Georgia before moving to Belgium.

Research by Lika Jalagania, an independent gender equality consultant and invited lecturer at Tbilisi State University’s Gender Studies Program, shows that 93.1% of respondents agree that LGBTQ+ people in Georgia have less access to employment. Additionally, 54% of respondents would choose a low-wage job where they could express their identity freely over a higher-paying job without that freedom, just as it happened for Katalina Jorjeuli. Not being able to be who she was in the military system. “It felt like they knew it. After coming out, I still worked there for one year and every day was hell,” mentions Katalina while talking about the past experience within an environment that would never allow her to be her true self.

Being queer is also a barrier in education. Lukas Ablotia, a19-year-old Georgian queer refugee, received death threats while studying at university. Due to the administration’s inaction, he had to leave school. After ten months in Belgium, he will start university in September. The research “Social Exclusion of LGBTQ Groups in Georgia” shows that 32.2% of Georgian students have experienced homophobic discrimination by teachers, and 41.9% have been bullied by classmates.

“Society is to blame for being aggressive; I am not at fault,”

says Lukas, showing the building where he went through the asylum procedure. Leaving Georgia was his only option for safety. “I remember when I got threats, I asked the dean of my school to do something about it. He did not, so I eventually had to drop out,” says Lukas, as he talks about how much he loves journalism, the field he studied back in Georgia. He shared many of his passions he could not work on because of constant discrimination.

- Lukas Ablotia

- Katalina Jorjeuli

Process of Seeking Asylum

Liselot Casteleyn, Doctoral Researcher at Ghent University, who has been working on a topic of queer refugees for almost three years now and has interviewed 50 people, including 10 Georgians, found that there was a community in Belgium that had arrived earlier and maintained contact with people still in Georgia. Liselot has also volunteered at the Rainbow House, the biggest LGBTQ+ organisation in Belgium and seen many queer refugee seekers.

Liselot highlights that while the Belgian asylum system is generally faster for Georgians, each case still requires a careful individual assessment to determine the level of danger they would face upon returning to Georgia, which is tightly connected to a statement made by Secretary of State for Asylum and Migration Nicole de Moor: “The asylum procedure is intended for those fleeing war violence or persecution, not for those seeking better economic conditions.” Georgians must establish that they are individually in danger if they return home, which is the case for Katalina and Lukas.

"If I go back, they are even ready to kill me"

says Katalina.

Doctoral Researcher Casteleyn noted that the asylum procedures for Georgians in Belgium are expedited compared to other nationalities, with applicants often experiencing shorter wait times in reception centres, which further attracts asylum seekers from Georgia. As the asylum information database shows, last year 911 Georgians applied for asylum. “The goal is to handle applications from low-protection countries (Georgia, DR Congo, and Moldova) within a period of 50 working days. We ensure that people quickly know where they stand. This is good for everyone,” mentions Secretary of State for Asylum and Migration Nicole de Moor on her website.

Julia Kundler, a legal adviser for the Rainbow Refugee Committee, discussed the experiences of Georgian refugees who, traumatised by their past, feared even simple acts like holding hands in public. She also drew comparisons with other regions, noting, “Individuals from conflict areas, such as Cameroon or Tigray where genocide occurred, often bear deep trauma. This trauma frequently drives them to seek solace within their own communities, sometimes at the expense of concealing their sexual orientation to avoid being ostracized.”

‘I miss my country but I have to be here now. Brussels took me as I am’ – says Katalina Jorjeuli as she starts walking towards the noordstation on her way home. “the toughness that comes with adaptation makes me think of Georgia, but then I am reminded with why I had to leave in the first place” – mentions Lukas Ablotia. Brussels has turned into safety net for Ablotia and Jorjeuli.