UNESCO, UNIDROIT, Interpol, ICOM, The Art Loss Register, the Open Restitution Project in South Africa, the Benin Dialogue Group…

The list of organizations working to return looted art to its rightful owners is getting longer. But while the goal sounds noble, ‘just give everything back’, the road to restitution is more complicated than that.

So, what is looted art exactly?

The United Nations gives the following definition: Looted art refers to cultural property that has been unlawfully taken, especially in the context of armed conflict, occupation, colonization, or illicit trafficking, and which, under international law, should be returned to its rightful owner or country of origin.

Curators of museums still find it a difficult topic to give a clear and definite term to. “I find the term looted art uncomfortable”, says provenance researcher Ilja Labischinski from the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin. “We’re not only talking about art objects. Some are seen as everyday objects, others are sacred or ceremonial. And it’s not always easy to define whether they were taken under colonial conditions or not.”

A little historical context

In the days when Europe was a continent of colonizing as much a possible, it ‘collected’ a lot of art objects too. While the metropoles maintained control over its overseas colonies, it took a lot foreign objects back to Europe. Some objects were bought or ‘gifted’. However, many were taken by force, under threat, or under unequal power dynamics. It’s estimated that European museums and institutions hold between 1 and 1.4 million African objects alone. The actual number may be even higher, especially when you factor in unregistered private collections.

According to Dutch historian Lodewijk Wagenaar: “In The Netherlands VOC agents took objects back home in the name of God and profit – and it wasn’t just condoned, it was considered scientific progress.”

Nowadays, we have turned our faces 180 degrees and look very different to this topic. Looted art raises discussions, and sometimes even protests, about the question if we can still have it here in Europe. Lodewijk Wagenaar said in the Dutch mini-series ‘Roofkunst’: “If you impose our current attitude towards looted art on our ancestors, you will have 2 million scoundrels in the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. Then there is nothing right anymore.”

It has become a sensitive topic to talk about, because it touches on issues of heritage, identity, and historical injustice. And the European continent is not averse to historical injustice.

Calls for return

So what do countries of origin say?

Representatives from countries of origin stress the importance of restitution. Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare, whose work often revolves around colonial history and restitution, notes in The Guardian: “It is essential to preserve history and keep memory alive.”

Shonibare refers to the Idia Mask, a key artefact brought back from Benin by the British Expedition of 1897. The mask became the symbol of Festac ’77 – the second world festival of black and African art and culture – after the British Museum refused to loan it to Nigeria.

In Sri Lanka, the government has repeatedly demanded the return of the Kandy Cannon, a major cultural asset currently in the Netherlands. Sri Lankan authorities stress that such objects are of great importance to their national identity and cultural heritage.

Restitution: diplomatic and legal obstacles

That it is a complex topic becomes clear when countries are asking their objects back. Now diplomatic and legal obstacles come in play. Because it cannot be sent back so easily. Obstacles like safety, money and caretaking play an important role in restitution.

For the return of objects to its original owner, UNESCO can help. As an international mediator it made an international agreement of the restitution of cultural heritage with the Convention of 1970.

In the Netherlands, the government weighs the significance of an artifact to the Dutch public against its relevance to the country of origin. Journalist and colonial history expert Jos van Beurden explains: “The legal framework in the Netherlands supports restitution, but it’s still a case-by-case process. Political will plays a major role.”

In 2007, with the Kulturgutschutzgesetz Germany amended its existing cultural property law, complying with international conventions such as the 1970 UNESCO Convention. However, it doesn’t cover most items acquired during the colonial era. Julia von Sigsfeld, a restitution officer at Berlin’s Ethnologisches Museum, notes: “The legislation applies only to objects illegally imported after 2007, but not to the vast majority with colonial provenance. We have to rely on ‘political will’ and institutional ethics.”

Modern ways of exhibiting

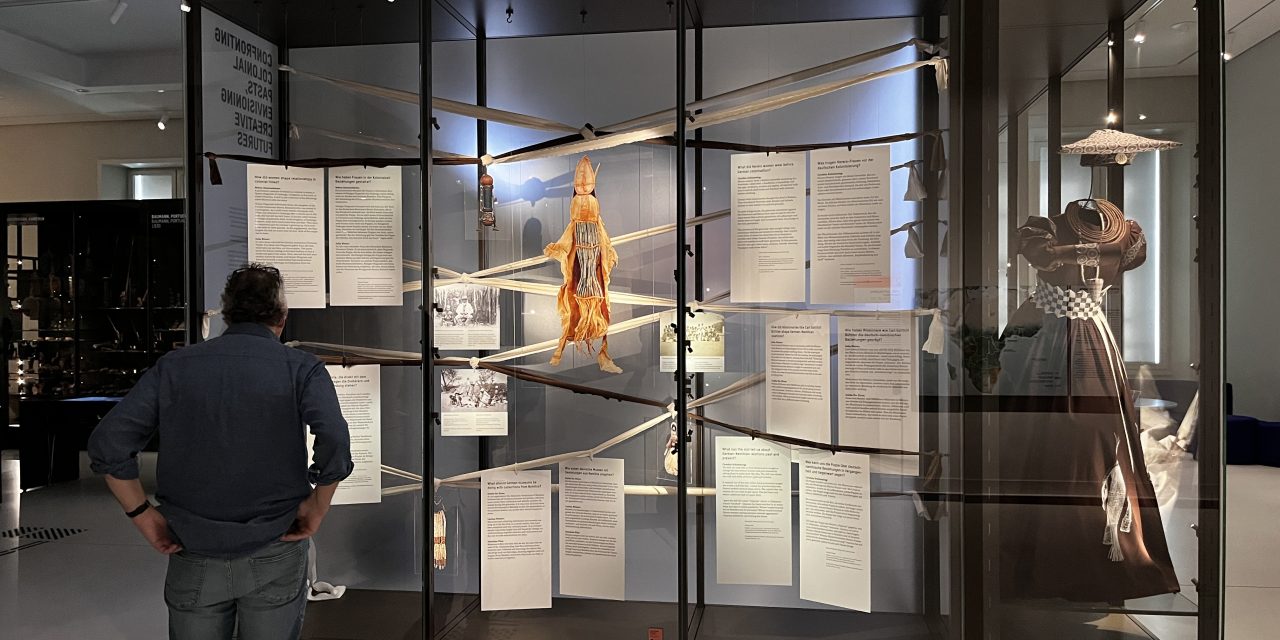

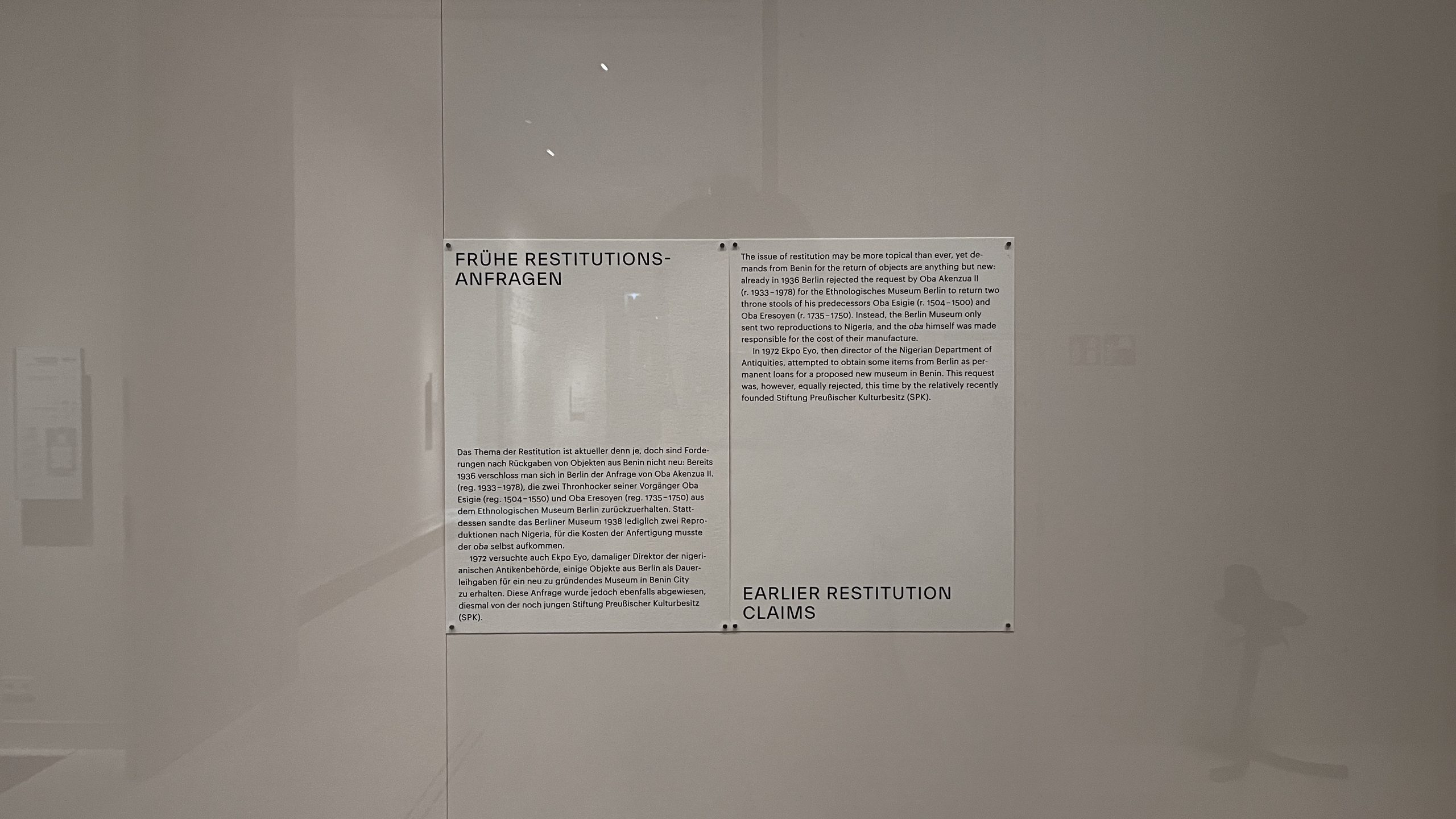

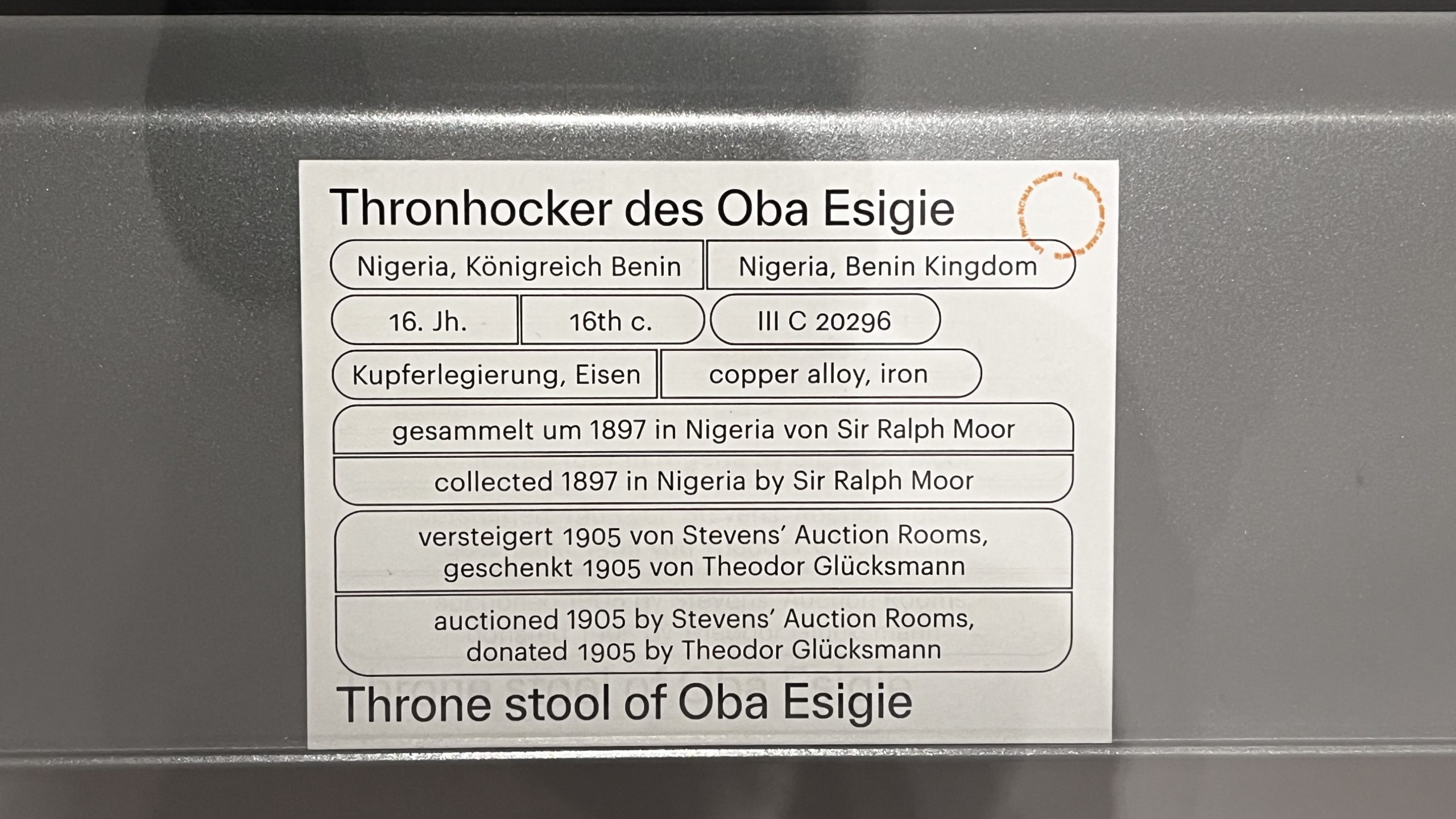

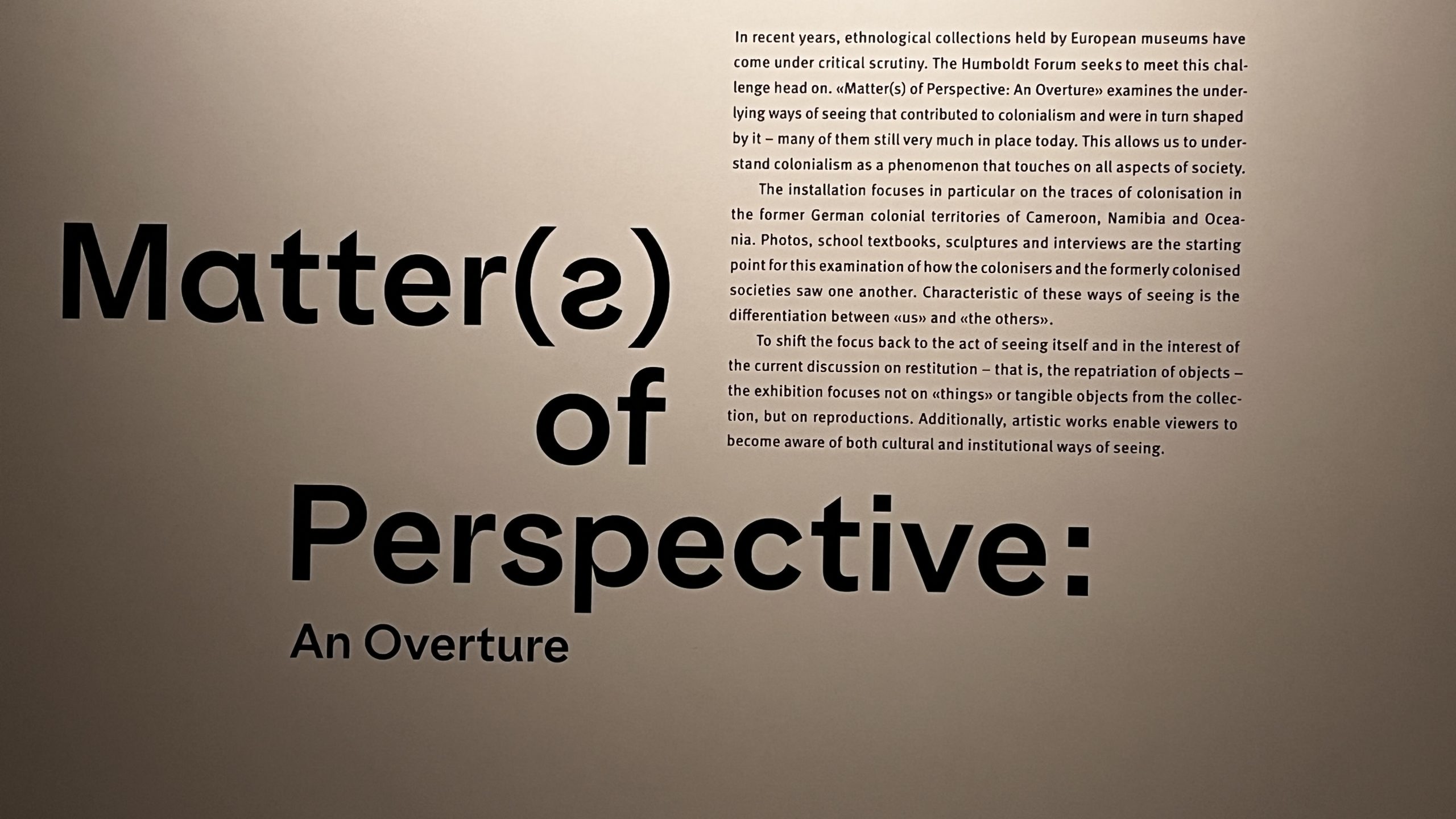

As the debate continues, some museums are exploring alternative ways to display disputed objects or even choosing not to exhibit them at all. Take the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, which holds several Benin Bronzes from Nigeria. They exhibit objects as a part of a long-term loan from Nigeria. Ownership remains with Nigeria, and contextual information is prominently displayed.

One exhibition room features no artifacts at all. Only papers explaining what used to be there and video statements from Nigerian cultural ambassadors explaining the artifacts’ significance.

At the Mauritshuis in The Hague, virtual reality technology has allowed visitors to explore objects that were returned. Offering a digital compromise between access and restitution.

So, modern technology can help us finding a middle ground between showcasing looted art and sending it back to its original owner.

In the end, restitution doesn’t erase the past, but it does acknowledge it. That matters. Especially when you listen to the people whose histories were displaced.

In the next video you will hear Egyptologist Daniel Soliman from the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden talk about new ways of exhibiting looted art.

In this video, you will hear me talk about what happens next after an object is returned to its country of origin.