Refusing to surrender to Italy’s right-wing tide, Bologna is emerging as an island stronghold of the opposition. Despite its resolute stand, the city struggles against the immense obstacles of the changing political landscape.

“The municipal government of Bologna, I think you could say, is the most left-wing municipal government in Italy. There is a kind of permanent clash between the municipal government and the central government that defines the situation in the city”, says Sandro Mezzadra, who teaches political philosophy at the University of Bologna.

Piazza Maggiore and its flags. The word Pace is set in big white letters against the pride rainbow.

The city of Bologna itself is bustling with students talking in groups, smokers leaning against walls outside cafes lined with pastries, and vendors setting up colorful displays beneath market tents. Bologna’s central plaza, Piazza Maggiore, lies past colorful buildings of pink and orange, down streets covered by arched Porticoes, and past walls lined with posters petitioning for social rights, something less commonly found in other cities. Three flags fly in the square, one for Italy, one for the EU, and one for Peace.

The warm colours of Bologna’s buildings.

Bologna’s citizens go about their lives.

A woman wraps up freshly made pastries, a part of daily life in Bologna.

But even in progressive Bologna, peace is not always on the daily agenda. On an innocent-looking street, posters reveal the violence of December 6th, when the police intervened in a demonstration. The pictures show a young woman covered in dark bruises from head to toe. Professor Sandro Mezzadra tells what happened: “There was a demonstration close to the university. It was not such a big demonstration, but several hundred people participated and the response of the police was brutal”.

One of the posters shows a policeman with reinforced boots kicking the young woman between her legs. The photojournalist Michele Lapini published the image because “unfortunately there were no journalists to cover this demonstration, despite the dozens of people cleared, two solidarity garrisons that lasted more than twelve hours and a day of constant tension”, as he says on Instagram. The woman who was attacked wants people to know what happened, so on December 12th she put up the posters and gave a speech in front of the doors where the incident took place.

The street where the incident happened.

“The police charged from the back”

Professor Mezzadra waits outside the university’s philosophy building, smoking and answering students’ questions. After ordering an espresso at a nearby café, he recounts his experience of the demonstration on December 6th:

“The police charged from the back, very violently, and in ten minutes the police came from the front, which is something they don’t usually do because they leave people the possibility to escape. (…) I can tell you it is very, very strange. In my eyes, it was clearly a message.”

Professor Mezzadra reports on his experiences on December 6th.

The meaning of this message began earlier that day when the police cleared two occupations of empty buildings. The squatters were families and students who had nowhere to live. The police came that day, ignoring the negotiations that were taking place between the municipality and the occupiers. The people who took part in the demonstration were protesting against the harsh actions of the police in clearing the buildings. The demonstration was charged from behind, although there was no clash between the protesters and the police.

Housing is a big issue in Bologna, and the city council is well aware of this. These occupations are different from those seen before. “Until some years ago, the occupations were carried out by, let’s say, migrants without papers, without jobs. Now most of the people who occupy are workers,” says Mezzadra. “There were negotiations on both sides and yet the evictions began. It was a move against the municipal government. The police, of course, are part of the central institution”. A story of tension between Italy’s right-wing government and the left-wing government of Bologna is unfolding.

Silence of media and city council

Meanwhile, there are crickets in the Italian media regarding the incident. Apart from a small amount of local coverage, the press seems to have remained silent about the occupations and the police violence.

Francesca, a student at the University of Bologna, seems unimpressed by the Italian press when we meet her outside a study hall at the School of Medicine. “The traditional media are terrible, we don’t have a good liberal expression,” says the medical student with a silver nose piercing. She agrees that the international and national press does not cover this kind of police action: “You can find something in local magazines. Yes, you can see, for example, ‘The violence of the demonstrators – eight policemen in hospital’, this is the kind of article you can find. Without saying that they put families on the street in the cold season.”

The police are present at the main square in Bologna, Piazza Maggiore.

According to her, it is normal for the executive to become violent when tensions rise during demonstrations. As policemen in Italy do not have to wear identification numbers, it is difficult to identify those responsible for acts of violence. The girl who was assaulted on December 6th was only able to confront her attacker because there was plenty of photographic and video evidence. This is all the more distressing considering that one month after the incident in Bologna, on 7 January 2024, there will be a demonstration of neo-fascists in Rome who will make the Roman salute. They will also shout “presente”, as Mussolini’s fascists once did. And there will be zero police action.

Not only the Italian media but also Bologna’s city council have remained silent. Francesca, the president of the University of Bologna’s student council, does not feel any support from the city council. According to her, the deputy mayor visited the occupied building, but the city council has not yet publicly responded to the incident of police violence in early December.

“They say they care, but I don’t feel it. It’s more of a virtual thing. It’s more an electoral thing than real participation. For example, this event [police violence in early December] shows how fragile, how vulnerable, they are now. They have been badly confronted by Rome, by the state.”

A group of students cross the street on the edge of the University District.

What Bologna stands for

Despite her frustration with the city council, Francesca is happy to live and study in a city like Bologna:

“Living in Bologna is nice – if you like politics, activism, and if you have a place to stay. There is a good trans-feminist movement, there are anarchists. There are a lot of things and there is a lot of participation and teaching other people how to move. (…) Compared to other cities we are kind of resisting. It’s cool to see.”

Professor Sandro Mezzadra, sees the role and support of the city council differently. “Nowadays in Bologna there is a quite widespread awareness that negotiating with the municipality can be useful.” He highlights the role that organizations have played in making Bologna known for its activism over the years. “If you take a city like Bologna, the political landscape of the movement is characterized by the presence of organizations that are not [necessarily] NGOs, but have a kind of history, a legacy. In addition, several associations make up the third sector and are part of large networks”.

One example of the city’s initiatives is its community centers. Francesca Romana D’Amico, a member of the local council, shows around a building recently bought by the city, which is now a public space where people can meet, work, have a drink, or play cards. Romana D’Amico, an activist herself, says: “I think activism in Bologna is really interesting because there are a lot of different groups, so you can do very different things. I think the university is a crucial part of this activism because there are a lot of students, a lot of young people who want to do different projects, who have different perspectives on life and different ways of living their life”.

Francesca Romana D’Amico at the co-working space of the new community center.

Il Casalone is located in the suburbs of Bologna.

The fact that Bologna is something of a progressive island within Italy, a country that is becoming more and more conservative, is also reflected in its social welfare activities. “Especially here you have a lot of social services, a lot of attention to people with disabilities or social inclusion services, so I think this is specific to Bologna, in Italy, it is not always done in the correct way,” explains Romana D’Amico.

A city facing challenges

Despite the role of the city and groups in creating social inclusion, the city has seen a difference since Giorgia Meloni’s government took office on 22 October 2022. According to Romana D’Amico, in 2023 the government cut a lot of credit to citizens. This included the cancellation of previously planned social payments and student loans, which led to dropouts. The president of the student council confirms this. Another problem, she says, is the price of housing: “Because you cannot afford the rent, you cannot find a place to live. The danger is that we are changing the kind of students who go to university. We are going back to a luxury education only for the top financial players.”

People walking the stairs of Parco della Montagnola.

Professor Gianfranco Baldini, who teaches democracy and populism in Europe at the University of Bologna, agrees: ‘It’s a huge problem. We have buildings that have been abandoned by the Carabinieri, the military, and the police. They have been there for years, decades, and they could be converted into student accommodation. But it takes decades, literally, because of the way the public administration works, or rather doesn’t work”.

Despite these problems, student Francesca feels that “Bologna is still quite good, because compared to other cities or other regions, we are richer, we have more benefits from the university”. She calls for a more hands-on, face-to-face approach. This could be a possible goal for both politicians and activists. “We need to take care of the space, the people we meet, our relationships, and our community. Not everyone has the time and resources to be politically active. We can’t just start mobilizing when things start to affect us directly.

Bologna’s student district with its walls covered in calls to action and mementos of the past.

Piazza Maggiore at night.

How Bologna acts differently

Perhaps this is what sets the city of Bologna apart from other Italian cities. A sense of community and citizens who stand up for what they believe in. Historically, the people of Bologna have always taken a stand. Professor Mezzadra reflects on how movements of the past influence those of today: “In 1977 there was a significant conflict between the old left and the new left. This shaped the history of the city in the following decades”.

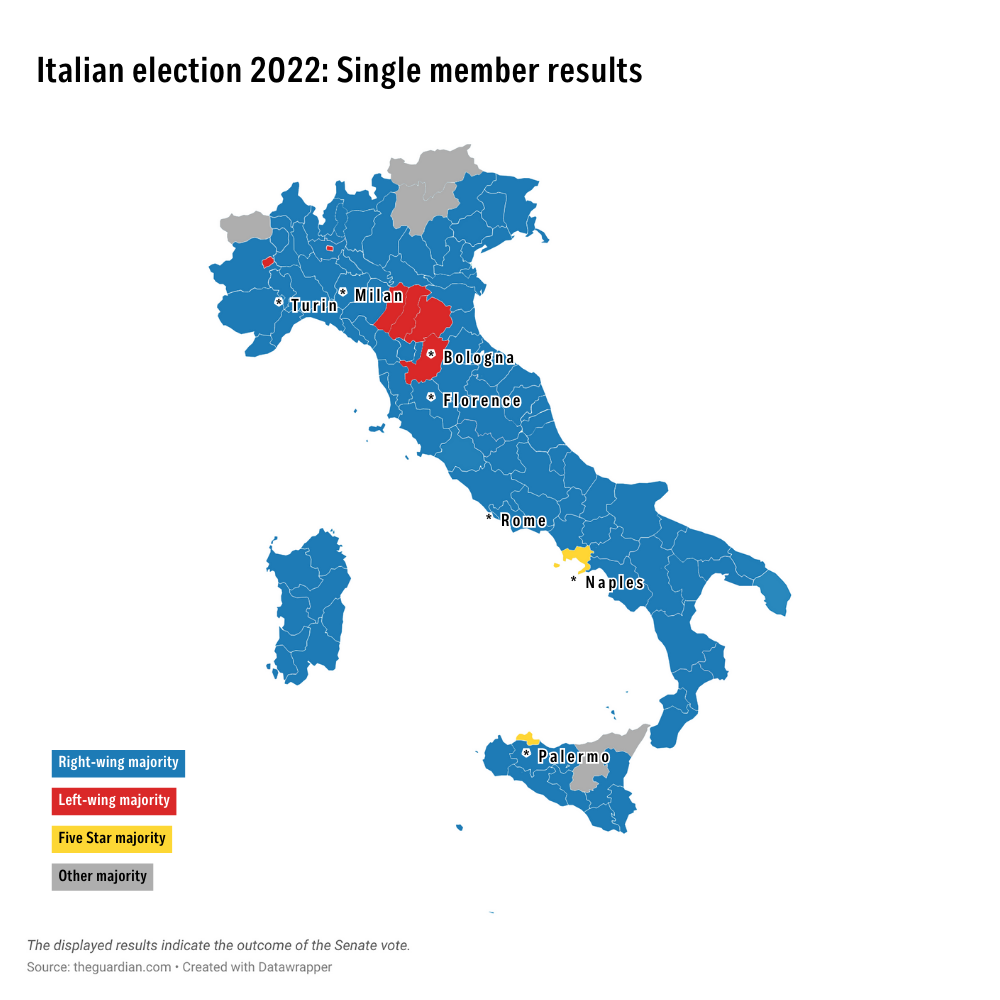

Bologna can be seen as an island in a country that is increasingly returning to the political movements of the past. In the 2022 elections, the region around Bologna, Emilia-Romagna, was the only region where the majority (45.5%) voted for the Democratic Party, the center-left force. Giorgia Meloni’s right-wing party, Brothers of Italy, gained more than 21 points in vote share since 2018. With 237 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 115 in the Senate, the party won a clear majority in Italy.

Italian election 2022, single member results (Senate).

Since the Fragile State Index assesses countries based on cohesion, political, economic, and social indicators, Italy’s score has been falling since 2021. The country is currently ranked 33rd out of 179 countries worldwide in the ‘more stable’ section, with ‘very stable’ Norway topping the ranking at first place. Within this somewhat fragile Italian state, Bologna was ranked second in the 2023 Quality of Life report by the business newspaper Il sole 24 ore.

Fabian Habersack, a researcher on right-wing populism at the University of Innsbruck, considers Bologna an interesting case:

“Bologna shows that it is possible to resist to a certain extent at the local political level. Even if you have a better right-wing new fascist government at the national level. I think it’s one of those good cases that shows that this is possible and important”.

The canals in Bologna’s historic city center.

Banners at Piazza Maggiore express the passion of the city.

In the face of growing political challenges, Bologna remains a stronghold of resistance, an island against the tide of right-wing influence sweeping Italy. The city’s commitment to its values, vibrant activism, and strong sense of community set it apart and paint a contrasting picture against the backdrop of a changing political landscape. As Professor Mezzadra says: “In recent years, Bologna can be characterized by a rising cultural activity, by a counter-culture, by social and political movements. These have led to the creation of a fabric of relationships between different people that continues to nourish political action in the city”. While the Meloni government flexes its muscles, the people of Bologna continue to resist, as the movements that took place in December have shown.

————–

Text & Photos: Anna Pentermann & Eva Unterrainer