London’s rapid expansion causes tension between urban development and the preservation of green spaces. As the city sprawls, land becomes scarcer, which drives up property values and thus creates conflict between high-profit ventures like apartment buildings and the essential, but less lucrative, gardens and parks. When perceptions differ among various stakeholder groups, it becomes challenging to secure votes for spatial planning initiatives, especially those favouring an area’s ecological potential. Gardens now face constant pressure to find new funding and prove their value beyond immediate financial gain. This struggle extends far beyond urban planning, directly impacting the quality of life and overall well-being of everyone who calls the city home.

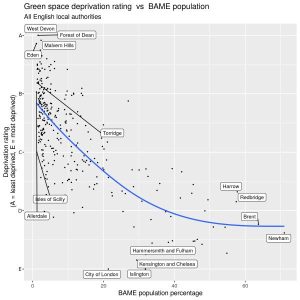

Recent research highlights that cities often praised for their “liveability,” such as Vienna—which held the top spot for three consecutive years—benefit significantly from their extensive green belts in addition to their economic factors. London, though celebrated for its iconic parks and gardens, presents a more nuanced reality. Although 22% of Greater London is covered by a green belt, much of this space is on the city’s periphery, making it less accessible for many residents. In London, employment opportunities and affordability are vital, but sustaining the high productivity that drives this prosperity requires a strong focus on health. However, this responsibility isn’t evenly distributed across England, with a notable correlation between green space deprivation, ethnicity, and income.

Deprivation rating vs BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic) population in England. Graph made by © Friends of the Earth Limited.

Who holds the power to implement and enforce policies that protect these spaces? In London, the allocation of green spaces is managed by the city government and local councils through zoning plans shaped by public consultation and influenced by various stakeholders, including developers, environmental organisations, and community groups. William Peel, a representative of the Society of Garden Designers, notes that this process is often complex and lengthy, taking years to balance the demands for housing and infrastructure while considering green space per capita, overall percentage of green space, and proximity to green areas.

Despite all the talk of balance a short-walk through London’s streets reveals that priorities often seem misaligned. The ongoing tug-of-war between conservation and development means policies can either safeguard green areas or open them up to profitable ventures. The result: Londoners are left with less than 9 m² of green space per person—falling short of the World Health Organization’s minimum recommendation. William claims,

I believe that decisions regarding green space creation, management, and enjoyment should involve clear and transparent participatory processes with all interested stakeholders. This is and should be seen as a right of urban residents rather than a unilateral government initiative which is a problem we often hear about before consultancy takes place.

Intense lobbying by private and public interest groups with conflicting agendas, such as neighbourhood communities and property developers, heightens the tension between preservation and profit. It would appear that currently the scales tip toward short-term gains at the expense of green spaces for long-term sustainability and well-being.

Experts like Tayfun Yalcin, founder of Towards Permaculture in Amsterdam, contribute their insights on how to turn the tide. As a specialist in sustainable landscaping, Tayfun emphasises the need to rethink our modern, consumer-driven lifestyle—one that is deeply rooted in monetary exchanges, industrialised food systems, and heavy reliance on pharmaceuticals. He believes these social limitations keep us from achieving true prosperity. Tayfun explains,

You see all the environmental issues that we call natural disasters. It’s a reaction from nature to our doings.

Despite efforts by environmentally conscious landscapers like Tayfun to challenge the dominance of multi-million-euro contractors and real estate companies, cities like London and Amsterdam face a common conflict. “No community owns land. Gardens are considered limited resources. The government has already sold the land. One day all this can go and become a big shopping mall,” Tayfun warns. While smaller spaces like his gardens offer social benefits, from promoting physical activity to alleviating stress, increasing demand for urban development often sacrifices quality for quantity. Green spaces gain true value when diverse activities converge and amplify each other’s impact. Research shows that these areas are most effective when located within 300 metres.

Yet, London’s City Hall estimates 66,000 new homes are needed annually to meet population growth, which could threaten access to these spaces for everyday use. Tayfun suggests that London, ranked 43rd in liveability, could improve by embracing community gardening and participating in workshops, offering a peaceful yet powerful alternative to protests for driving change.

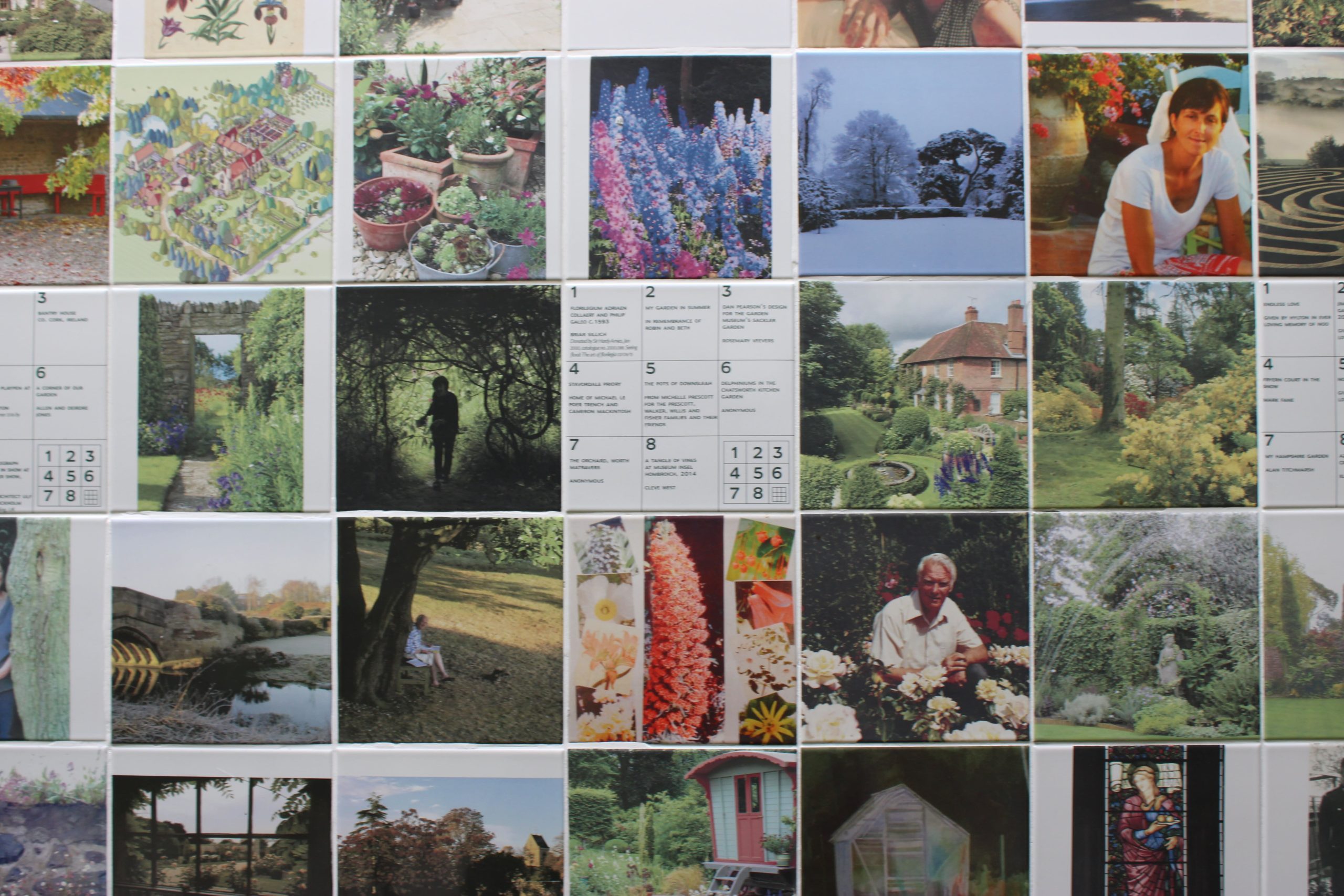

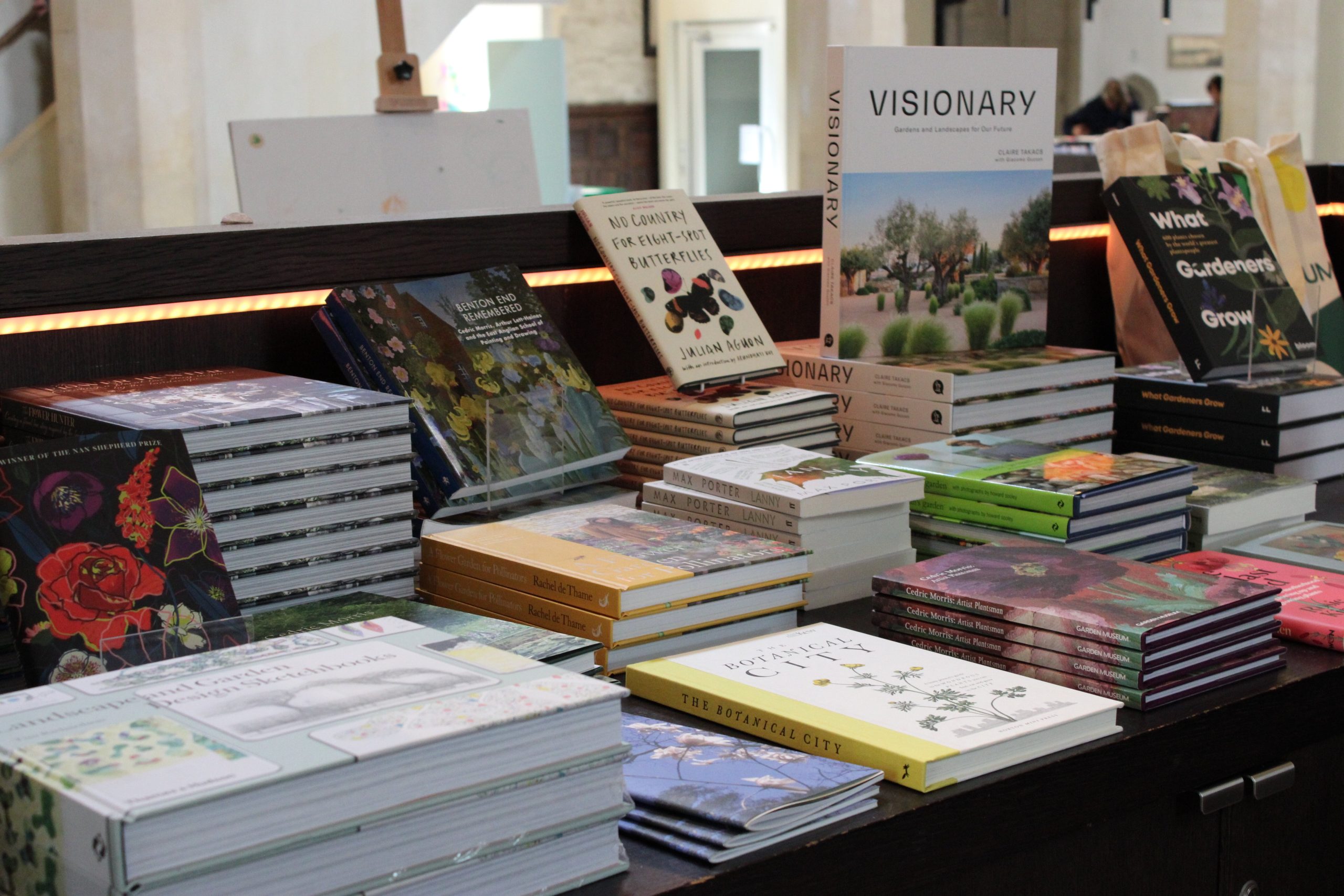

The Garden Museum

A former church along the River Thames has been transformed into a museum that houses galleries dedicated to the history of gardens in Britain. These exhibits highlight how plants that endured long voyages have become crucial components in our lives, from gardening competitions among royals to the first medicinal plant research among indigenous tribes. The museum’s outdoor area features a public garden, surrounded by spaces for biology and cooking classes, as well as art workshops—a peaceful retreat from the fast-paced modern world.

George Hudson

George Hudson, the museum’s Garden Curator, has been instrumental in his persistent advocacy at city council meetings and conferences; the museum’s local garden—despite being on land they don’t own—continues to flourish. The garden, though beautiful, is underutilised and outdated. Urban developments like new junctions and cycling paths have stifled expansion plans, including a pavilion for gardening volunteers and apprentices. Maintaining and creating green spaces within the city presents significant financial and bureaucratic challenges. George claims that installing a small sidewalk garden can cost up to £27,000 due to complex regulations and logistical hurdles, raising doubts about the city’s green agenda and exposing a façade of inefficiency and red tape.

Community garden several meters down the road.

St. Mary’s Garden located right next to a junction.

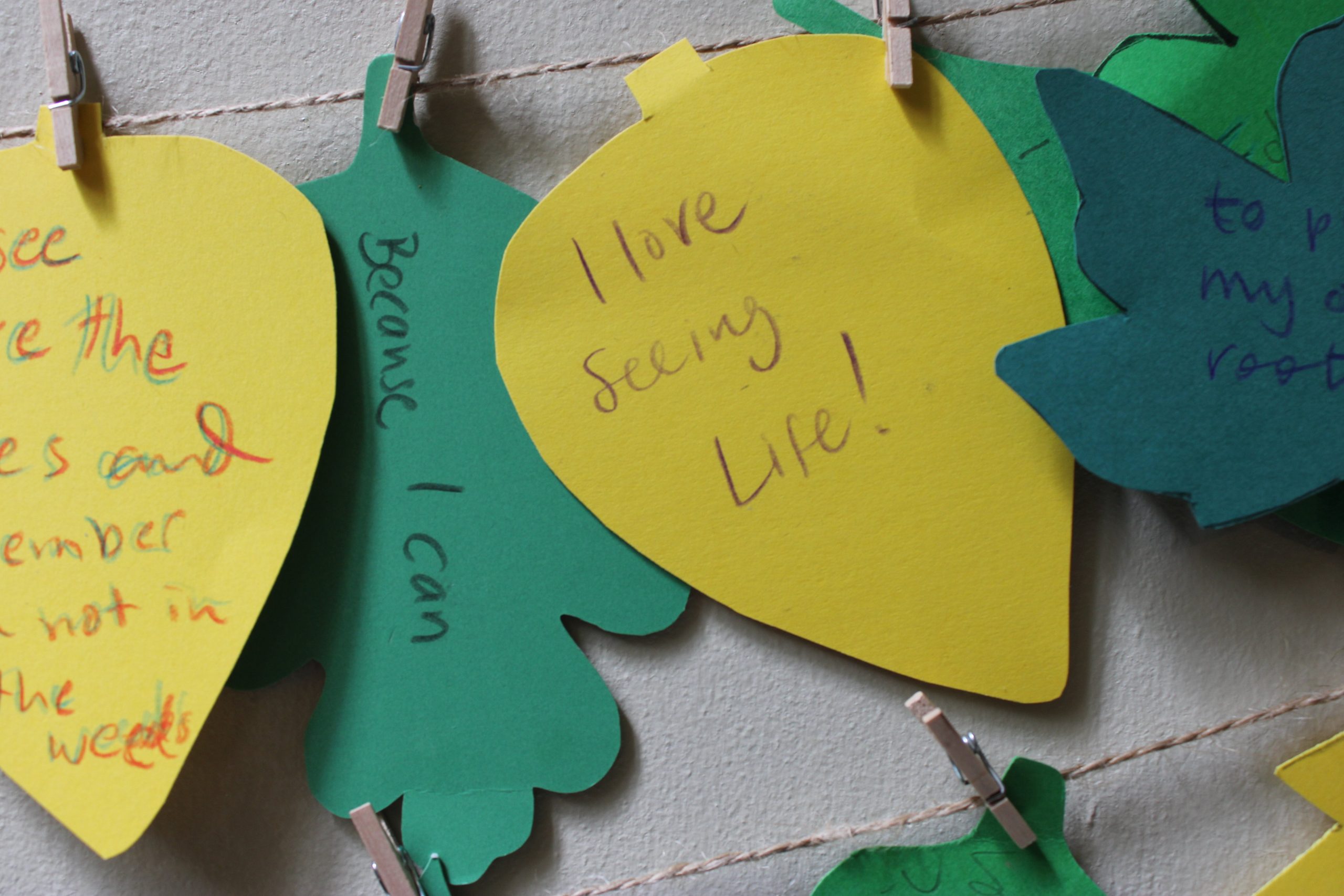

Despite these challenges, the Garden Museum remains resilient, fuelled by community spirit. Collaborations like the community healing garden with Lambeth Council provide a much-needed sanctuary for residents, especially the disadvantaged. Programs such as “Sow Grow Eat” equip young people with essential gardening and cooking skills, reconnecting all generations to nature.

However, whether these grassroots initiatives can withstand the relentless pressures of urban development remains uncertain. George reflects on the museum’s narrow escape from demolition 40 years ago, saved by the Trevis Kent Trust. “We have a long lease on this; the building will be here forever now,” he insists. Yet, the battle is far from over, as historical sites like the Garden Museum must continually fight to preserve their sanctity while London’s skyline evolves. This underscores the harsh reality faced by institutions in the charity sector, which must work harder to survive compared to public parks with government backing.

Chelsea Physic Garden

Another unfortunate casualty of this system is the Chelsea Physic Garden, a hidden gem behind four walls that houses over 4,000 plant species gathered from around the globe since 1673. Originally an outdoor classroom for apothecaries to learn about medicinal plants, the garden has evolved into much more. In 1983, it became a charity and opened its gates to the public, transforming into a sanctuary not just for plants but for people overlooked by society.

Shivani Patel

Shivani Patel, the Community & Youth Engagement Manager, is at the heart of this mission, focusing on breaking down the barriers that keep marginalised groups from experiencing the garden’s wonders. “The audiences I work with are the ones that are underrepresented at the garden. They’re not going to be a visitor,” she says. Within a city dominated by skyscrapers and soaring housing costs, these groups—young people aged 13 to 25, individuals recovering from addiction or bereavement, ethnic minorities, refugees, asylum seekers, and non-English speakers—feel alienated or financially constrained, but Patel’s outreach and tailored programs ensure everyone feels welcome. Patel shares,

My role is to make the garden accessible in more ways than one to audiences who wouldn’t normally come.

Glasshouses with diverse environments, such as this tropical corridor.

Learning center for different workshops.

This serene sanctuary, where people reconnect with nature, is navigating new ways to sustain its relevance through creative activities and tailored programs as it faces an uncertain future. With growing land scarcity and financial pressure, the Chelsea Physic Garden’s prime location has attracted commercial interest over the years. Shivani Patel and her team have had to innovate in generating funds, turning the garden into an experimental host space for events like engagement parties and the Dash of Lavender festival for LGBTQ+ History Month.

“Renting out the garden for private events helps us continue our mission while generating necessary funds,” Patel explains. While her efforts may seem small compared to the £5.5 billion the government is urged to invest over five years to improve public access to green spaces, they have a lasting impact. Despite its current stability, the garden’s future remains tied to the priorities of its landowners, the Cadogan family.

While there is no immediate threat, the potential for shifts in priorities remains a constant undercurrent.

Urbanisation casts a long shadow, constantly reminding us that these green havens are—and have always been—at risk. Investing in green spaces should be a priority, especially in neighbourhoods where access is limited, such as the 1,108 areas in England rated E, home to nearly 10 million people. Although green spaces can elevate property values and enhance urban development, they also bring challenges like gentrification and the commercialization of public spaces. The focus on property values often fuels speculative development, where green spaces are created more to attract wealthy buyers than to meet the community’s social and environmental needs. This trend can push lower-income residents out of their homes, increase living costs, and diminish the healing potential of these spaces, leading to the displacement of established communities and the loss of cultural heritage.