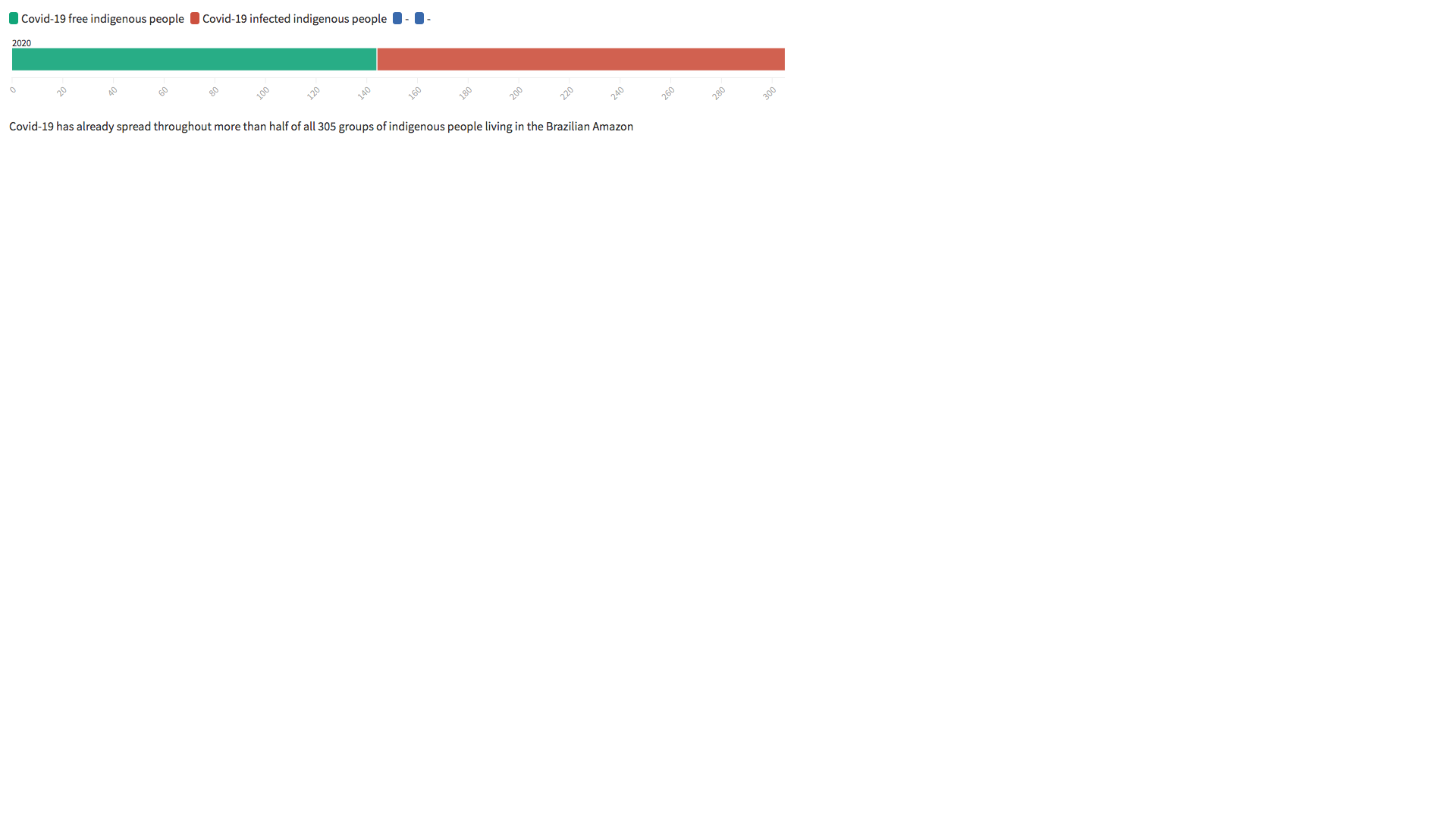

The Covid-19 pandemic has disproportionately hit indigenous people living in the Brazilian Amazon. This is especially affecting the elders, the most important carriers of indigenous culture. This new threat to the continued existence of indigenous peoples and their cultures, adds to the day to day threats these people already face.

Deforestation of Amazon rainforest

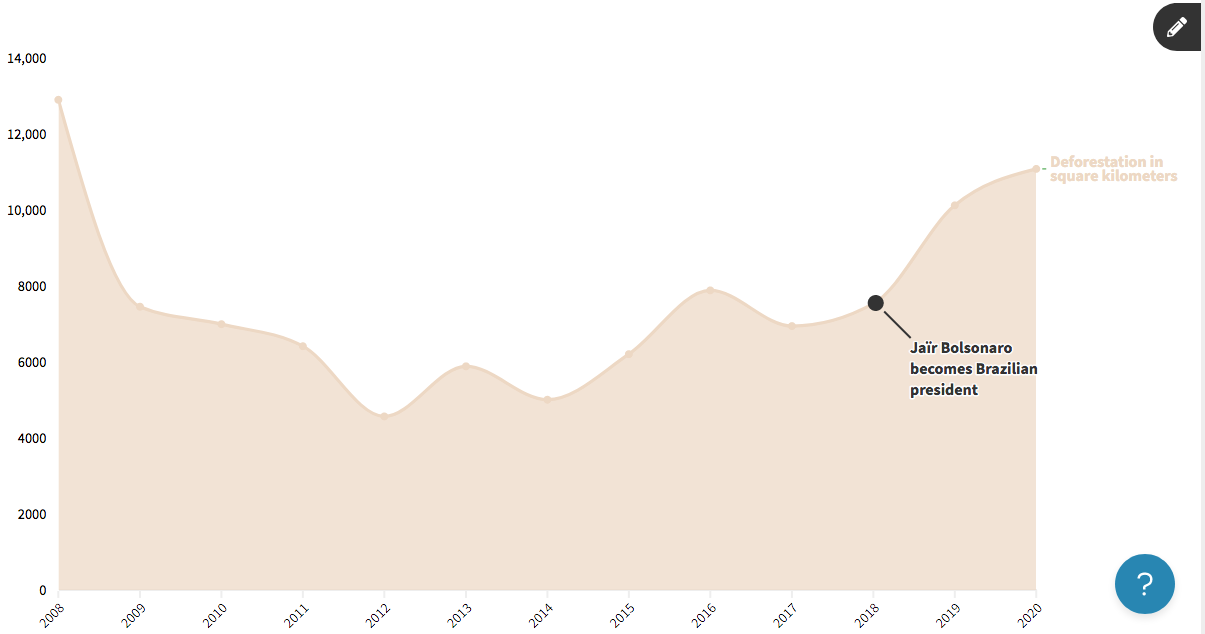

Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon is at its highest level since 2008. From August 2019 to July 2020 over 11,000 square kilometers of Brazilian Amazon rainforest was destroyed. An area similar to the surface of Jamaica. The valuable trees are – often illegally – logged, and then sold to international markets. The rest of the forest is burned, exposing nutritious soil. By doing this, the land is no longer considered primary rainforest, and therefore it is possible to start agricultural activity.

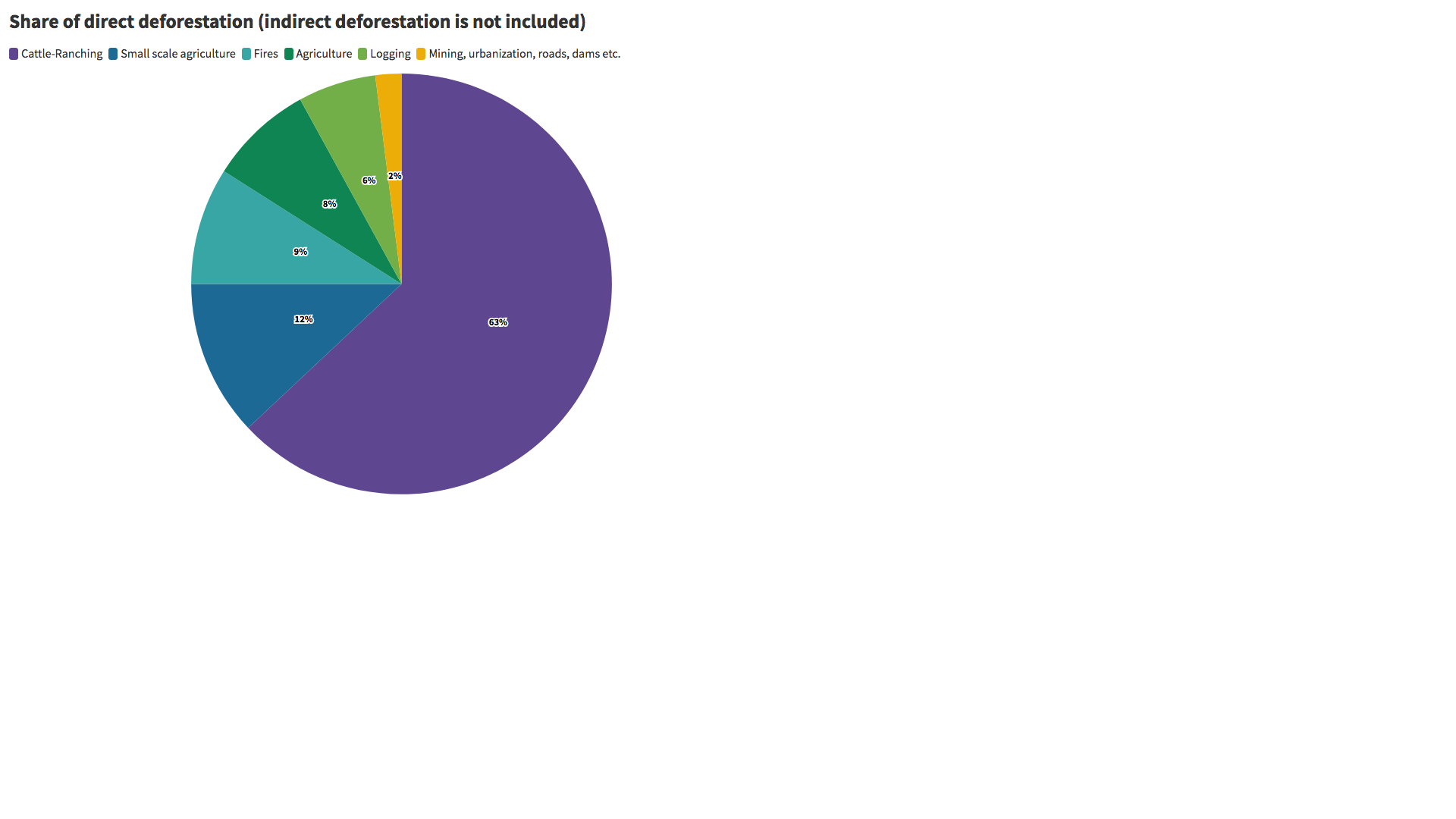

Cattle ranching is the main accelerator of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest, as 80% of deforested Amazon jungle is used for cattle ranching. Approximately 450,000 square kilometers of former Amazon rainforest is now used for cattle ranching. Totaling over 200 million heads of cattle grazing on former Amazon soil. Most of this beef is being consumed domestically, although Brazil is the world’s second largest exporter of beef at the same time. Other reasons for deforestation include soy, palm oil, cacao and maize cultivation. Brazil is the world’s second largest exporter of soy, which is mainly exported to Europe and China.

Indigenous on the defense

Several collectives of indigenous people have protested against logging. One such group is the Guardians of the Amazon. The group consists of 120 indigenous Guajajara, an indigenous community living in the East of the Brazilian Amazon. They are fighting the illegal deforestation of their Araribóia indigenous reserve. The Guajajara share the reserve with a small group of uncontacted hunter-gatherer Awá people still living deep inside the woods of this reserve. The Awá are in voluntary isolation, meaning they are not allowed to be contacted by civil society unless they make the first step.

Brazilian anthropologist Barbara Arisi, guest lecturer at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, says isolated groups know about the rest of society. “They see us in boats and planes. They know. And they don’t want to be a part of global society,” she says. In the 1500s, when mainly Spain, as well as Portugal and France colonized South America, they brought death and destruction along. This association – contact with outsiders – still means that in many cases the indigenous people see outsiders as harmful.

Indigenous killed in defense

Violence against indigenous people fighting deforestation has recently spiked in the Brazilian Marañhao state. In the Araribóia indigenous reserve, five members of the Guajajara people have been assassinated in six months, between the end of 2019 and the beginning of 2020. Firmino and Raimundo, both Guajajara leaders, were killed in a drive-by shooting while driving back to the reserve on their mopeds. Paulinho, also a Guajajara leader, was part of the ‘Guardians of the Amazon’. He was ambushed and killed in the reserve at 26 years old. Erisvan, 15 years old, was stabbed to death and dumped on a football field. The latest victim, Zezico, was a local leader, former teacher and supporter of the ‘Guardians of the Amazon’. He was shot near his village.

Mining in the Amazon

Mining for gold, copper, nickel and manganese is also a reason indigenous people are protesting, leading to murders of their leaders. Alessandra Corape from the Munduruku tribe has experienced infiltration of her territory firsthand. Mining company Anglo American, based in the United Kingdom and South Africa, has applied almost 300 times to start extracting gold in the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Reserve, where Corape lives.

Polluted environment

More mining in the region would mean further pollution of their territory. Since Bolsonaro has been in power, protected indigenous reserves have been opened for new mining projects. Rarely, indigenous people have legal land rights. This makes it complicated to defend what they see as their territory, since international companies have their eye on the resources found on that territory.

“There are entire communities drinking river water polluted by the mines. Our children are sick due to the high levels of mercury in the water,” says Corape. In October last year she won the Robert Kennedy Human Rights Award in the USA for her efforts in protecting indigenous people.

When a mine is opened in the Amazon rainforest, pollution is a consequence. For gold mining, the highly toxic mercury is used to clot together the gold particles, but once used, this is disposed of in the rivers. Anglo American, one of the biggest mining companies in the world, has submitted 296 applications for mining operations inside indigenous territories since the 1990s. Operations which could pose a huge risk to indigenous people, as their rights and wellbeing have been systematically put aside by such multinational companies seeking to exploit the Amazon riches.

Corape stresses the importance of the consumers’ role in the process. “It’s Europe and China buying the products extracted here. But do the companies and buyers realize there are people living here? The developed countries buy the products whilst it equals our death,” zsays Corape.

The domestic policies of Jair Bolsonaro

Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro entered office in early 2019 and has since then made several changes that increase economic activity in the Amazon rainforest. Previously protected indigenous reserves, such as the reserve where Corape lives, have been made available to mining, logging, oil and gas companies. The veto right of indigenous peoples has been removed, and the planting of transgenic seeds has also been introduced.

Paralyzed protection

“Indigenous people are having a very hard time since Bolsonaro came into power,” says anthropologist Felipe Milanez, who has previously worked for FUNAI, the Brazilian agency to protect the environment and indigenous people. “At first it was extraordinary we had FUNAI protecting the indigenous, but now Bolsonaro has almost halved FUNAI income.”

Arisi mentions the effects of this. “Since the government is no longer protecting the forest, the indigenous are doing it. This results in many of them being killed,” says Arisi.

Munduruku activist Corape sees Bolsonaro as a cause of many problems of indigenous people. “Brazil has a leader who doesn’t care about indigenous people. He is against everything we support, and only wants to exploit the flora and fauna of our forest,” she says. But the forest is crucial for the survival of the 305 indigenous people of Brazil. “It is where we get our food and our water, our shelter and our medicine,” says Corape.

Maial Paiakan is also affected by Bolsonaro policies. She is a member of the Kayapoó tribe and her father was one of the most famous indigenous people striving for protection of the forest. She says: “We have a negationist government here in Brazil. Us indigenous peoples have been directly affected in many ways. There is a high rate of deforestation and many garimpeiros (goldseekers) are occupying our territories illegally.” This has increased since Bolsonaro came into power, she says.

Not all indigenous on the defense

However, anthropologist Arisi includes that indigenous people have differing opinions amongst them also. “We always see indigenous people as the ‘nature defenders’. But there are also indigenous people supporting Bolsonaro, and for example mining.” In the case of the Munduruku, however, everyone was against mining.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil

The COVID-19 pandemic also causes death in the indigenous communities. Indigenous communities have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. As indigenous practices and culture cause the virus to rapidly spread amongst the community ones its introduced. Moreover indigenous people have difficult access to primary healthcare and are not sufficiently being protected from the virus by Brazilian government, according to a study conducted by Oxford University.

The UN is also concerned: “Indigenous communities already experience poor access to healthcare, significantly higher rates of communicable and non-communicable diseases, lack of access to essential services, sanitation, and other key preventive measures, such as clean water, soap and disinfectant.”

Pandemic surprise

Corape was studying in a city several days from her home community when the lockdown commenced in Brazil. She quickly traveled to her Munduruku community and learnt many people there had no knowledge of the pandemic. “They didn’t know what was going on. This made me very worried,” says Corape.

Despite attempts to keep COVID-19 out of the communities, the indigenous suffered greatly. Paiakan’s father passed away in June as a result of the virus. Paiakan’s home state Pará was one of the states most infected by the virus. In total almost a thousand indigenous people have been killed by the virus so far.

Pandemic abuse

Milanez says that companies have “used the pandemic to start extraction of resources in the indigenous reserves.” The government is providing these permits for companies to enter the territories. “Amidst all the cruelty and violence, they are abusing the pandemic to invade the territories,” says the anthropologist.

Now more than ever, land rights are important to protect the indigenous people against such invasions. Since the pandemic has lessened law enforcement protecting the communities, the indigenous are forced to do it themselves, leading to many violent deaths.

“Many leaders have been murdered whilst protecting their land. They want to silence us. But we will keep on protesting for our survival. We have been doing that since the colonization and we will continue doing it forever,” says Corape.