Recent studies conducted in The Netherlands have identified the presence of pesticides throughout the landscape. However pesticides have been found in very low dosages, within legal norms, some scientists stress the lack of knowledge on the precise effect of these toxic substances. Margriet Mantingh, researcher and chairwoman of Pesticide Action Network Netherlands, sees a clear connection between the use of pesticides and the decline in insect populations. Jo Ottenheim, spokesman for the Dutch Crop Protection Association, stresses the lack of evidence for this claim.

Small in size, big in agriculture

The Netherlands may be a small country by surface, it is one of the largest countries when it comes to the agricultural industry. The Dutch agricultural export accounted for 94.5 billion euro’s in 2019. This places The Netherlands second, behind the United States, when it comes to the export of agricultural products. Although The Netherlands are 236 times smaller, the country’s agricultural export only differs 41 billions worth of agricultural export from the US. Through advanced technologies, ultramodern farming machinery, nice climate conditions, extensive scientific research and effective planned farming, the Dutch became masters at providing very high yields per hectare.

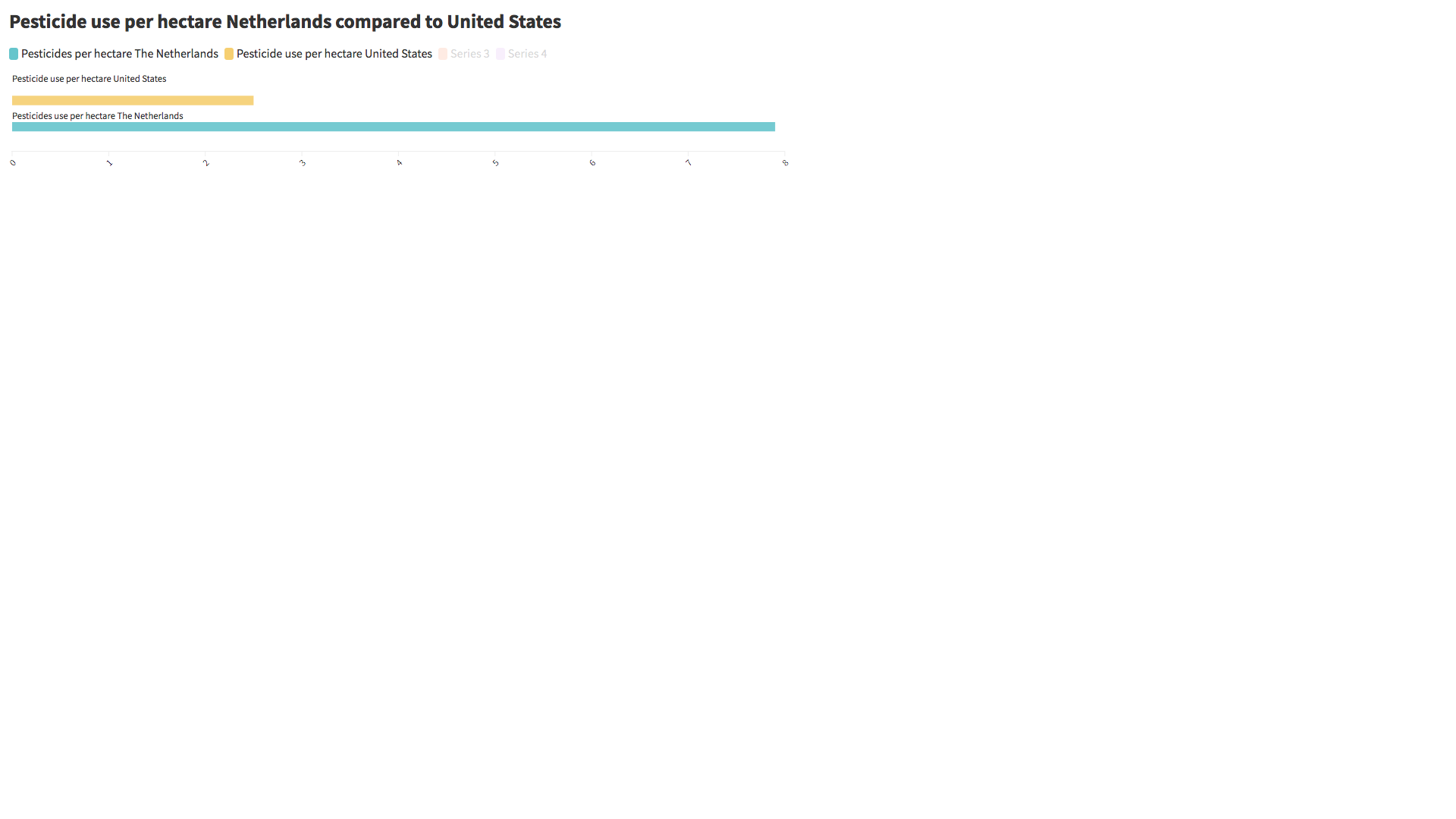

The use of pesticides, also known as crop protection products, is another reason for the high yields Dutch farmers are able to achieve on their lands. Pesticides are, according to the World Health Organisation: ‘chemical compounds that are used to kill pests, including insects, rodents, fungi and unwanted plants (weeds).’ In 2016 around 5.7 million kilograms of pesticides were used in Dutch agriculture. In comparison: the United States applied over 544 million kilograms to their fields and crops in 2016. The annual application of pesticides in the Netherlands, in average 8 kg per agricultural hectare, is one of the highest in the European Union. In Dutch agriculture the vast majority of pesticides are used to kill fungi and weeds. Very little, only 1.7%, of these pesticides are used to kill insects and mites. However in general the annual recommended dosage for fungicides and herbicides is much higher than for insecticides. Insecticides vary from 25 gram up to 500 gram per hectare, the annual dosage of a fungicide or a herbicide varies from 0,5 kg up to more than 2kg per hectare.

Pesticides possible effects

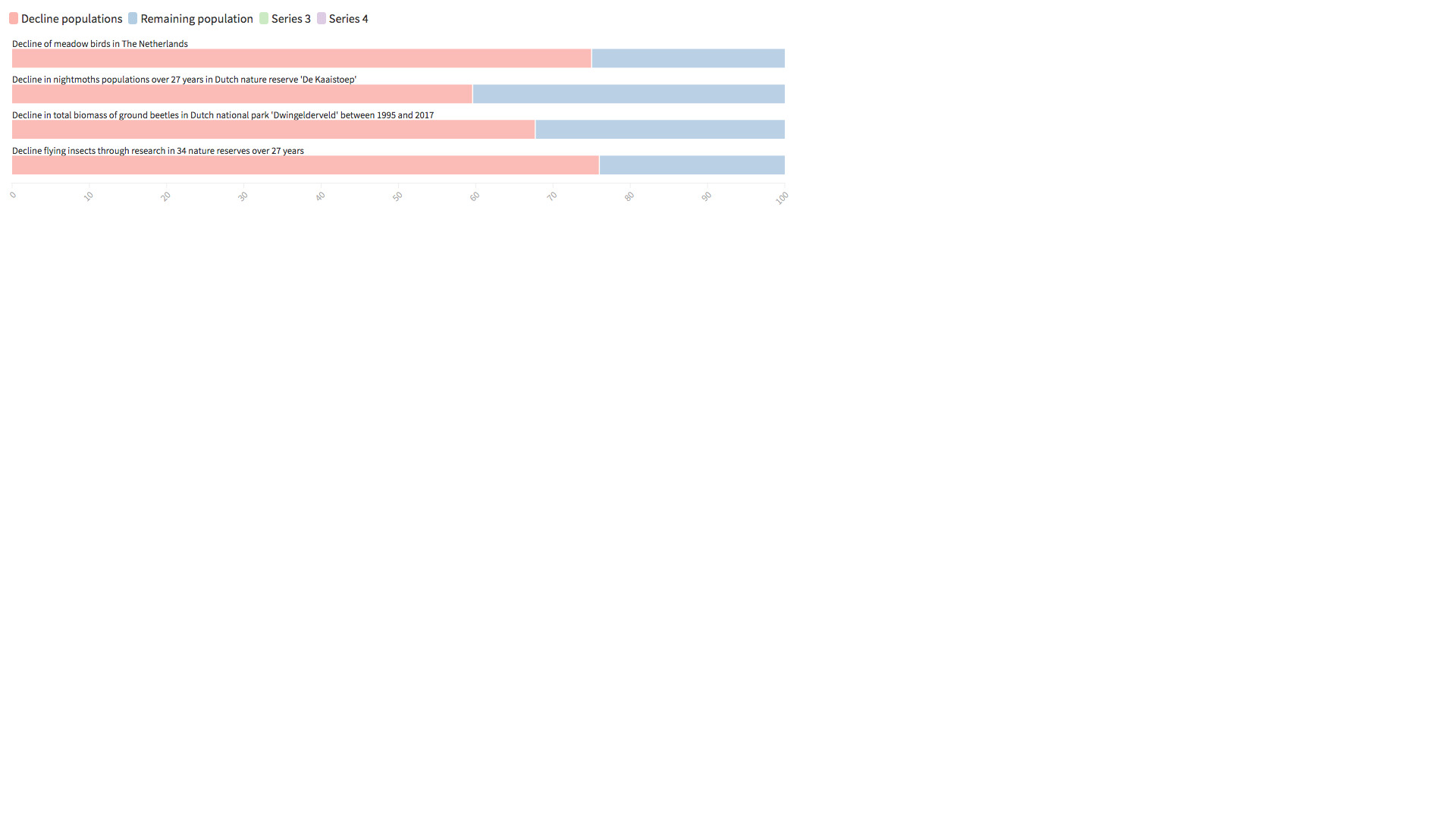

Margriet Mantingh, chairwoman for the Dutch Pesticide Action Network (PAN), is nevertheless extremely worried over the possible effect pesticides could have on nature. Especially the impact on small organisms, insects and insect-eating-birds is worrisome in her opinion: ‘Especially the last 20 to 30 years we see a huge decline in biodiversity. Even the most trivial common insects are dying. It’s impossible to just attribute all this devastation the deposition of nitrogen or to climate change’. Recent scientific research conducted across Europe indeed found a drastic decline in insect populations. Mantingh: ‘Scientific research has also shown that gadwalls, which are vegetarians do not suffer the same decline in population as similar duck species and other birds which rely on insects as nestlings. The entire food chain is affected by the drastic decline of insect populations.’

Mantingh also operates as an independent researcher, mainly conducting field research in The Netherlands and Germany. In her most recent research she and her colleague found a connection between the amount of pesticides in cowpats and the abundance of dung beetles present. Mantingh found, on average, 40 times more dung beetles in nature reserves than on cowpats in cattle farms. She attributes this contrast to the high amount of pesticides found on cattle farms. In the introduction of this research she strikingly states that it is ‘no popular topic’ to talk about pesticides as one of the possible reasons for the decline in insect populations.

Pesticides or crop protection products?

Jo Ottenheim is spokesman for Nefyto, also known as the Dutch Crop Protection Agency. An organization which represents twelve multinationals responsible for distributing chemical and biological pesticides, or as he calls them: ‘crop protection products’, to the Dutch agricultural industry. He emphasizes that ‘no conclusive evidence links the decline of insect populations directly to the use of crop protection products’. He furthermore underlines the ‘extremely strict admission requirements for the use and distribution of an existing or new crop protection product’. All pesticides are revised at least every ten years. Ottenheim: ‘you should see the stack of papers needed for admission of just one crop protection product, not to speak of the numerous scientific trials needed before admission is granted.’

Mantingh is not convinced. She denounces the admission process heavily: ‘In the admission trial for new pesticides only six, or even less different insects are taken to be examined. In no way six insects can account for our highly complicated ecosystem.’ Dutch nature is home to approximately 23.000 known different arthropods, of which insects make up the greater part. Mantingh: ‘The situations in which these trials take place do not in any way represent natural circumstances. Furthermore the trial duration is way too short. Only direct toxicity is measured. Long term effects, especially from generation to generation are in no way being measured. We have absolutely no knowledge of the long term effects of pesticides on insects or biodiversity in general.’

Ottenheim acknowledges the fact that a lot is still unknown: ‘we cannot research the effect of every pesticide on every organism, that’s simply not possible. The industry I represent tries to create responsible products for both farmer, society and nature. With the goal to have no harmful effects on human or animal health and no unacceptable effects on the environment. But in the end safety is not our main goal. We just acknowledge our products have been strictly examined’. He also underlines the fact that both farmers and consumers demand the availability of pesticides: ‘customers want spotless products and farmers focus on high yields. We simply provide these products within the legal frame presented to us by European legislation. At the same time we try to enhance responsible use of our products as well as developing more natural based crop protection products.’

More than just crop protection

The pesticides found in Mantinghs research cannot all be attributed to crop protection. Also many aspects of modern farms contain pesticides for conservation. In the presentation of her latest research she sums up the different sources of pesticides: ‘cattle-fodder, bedding for stables, veterinary medicinal products, contaminated surface water, contamination by use of pesticides in history, blown over pesticides and’. The presence of pesticides is simply part of preserving the materials/products: ‘In order to protect materials like hay, cattle-fodder or simply timber, pesticides are used to protect these products from damage and in order to store them. Many farmers, even organic farmers, are not even aware of the presence of these pesticides.’, Mantingh says. These pesticides then transfer to the cattle living in these stables, or eating contaminated fodder, resulting in cowpats and slurry which Mantingh describes as ‘toxic waste’.

Toxic chemicals in the environment are not just pesticides

In her opinion the danger lies in the ease with which toxic products like pesticides are introduced to the environment: ‘We are unaware of the precise consequences of these products and unable to later on retrieve these products from the environment. During my research I find a lot of pesticides which have been legally banned for almost 50 years. These are highly toxic substances present until this very day and for many more days to come.’

Both Mantingh and Ottenheim agree that the decline of biodiversity is not just caused by pesticides. It’s the apparent result of a complex interaction of conditions, combined with the intense use of the Dutch landscape. However they may differ in how they evaluate harmfulness of the exposure of this landscape to the use of pesticides. As Ottenheim puts it: ‘In all samples where pesticides were found, high values of other chemical residues were found. Substances which originate from many more industries than just the agricultural.’