It’s been 10 months since the world seemed to stop turning. People all over the world have been stuck in their homes because COVID-19 is making global rounds. Not a single country or individual has been unaffected until now, including terrorist groups like Islamic State and Al Qaeda. But what does it mean to them that virtually everyone in the world is at home? Do they see an opportunity in Syria or Iraq to start another insurgency? Will the number of terrorist attacks in the West decline? Could more young people be influenced and radicalised by all the extra time they spend behind their screens?

So what does this mean for terrorist organisations like Daesh, better known as Islamic State (IS)? Do they spend their days on the couch watching Tiger King or the Queen’s Gambit? We might never know, but one thing is for sure, the pandemic will have its impacts one way or another. “The coronavirus managed to do what jihadists wanted to do, but couldn’t: close bars, close nightclubs and install a kind of fear everywhere. It’s almost like this virus has common objectives with jihadist groups,” explains Laurence Bindner, expert in the field of terrorist groups and their media strategies.

Syria for example has 13,036 cases of COVID-19 and 832 deaths, according to the Johns Hopkins University. The estimated numbers of this country in ruins, might be a lot higher, but are unknown due to limited testing capacity. It was even mentioned by Syria’s World Health Organisation’s representative Akjemal Magtymova, who said in an interview with Reuters that Damascus and rural Damascus have been hit the hardest and that a lot of cases are still going unreported which means the actual number of COVID-19 cases is much higher. The amount of infections in Iraq is estimated a lot higher at 608,232 and 12,944 deaths, but these numbers have also been contested due to a limit in testing capacity.

“You can find social media accounts run by IS, which count the number of deaths in Western countries, which is of course portrayed as the revenge of God against disbelievers”, says Bindner. The coronavirus is a punishment from God, IS said. In one of their published articles they called the virus a punishment to all the states, mainly the West, encouraging their followers to keep on waging jihad and take advantage of the vulnerability and the saturation of health and security resources. Which is a very different approach from Al Qaeda, telling its followers to take advantage of the quarantine itself to ‘embrace Islam’ and learn about ‘authentic sources’. At the same time, these groups rejoice about the chaos the pandemic is bringing to the West.

The pandemic and the confinement that comes with it, will have multiple effects, some of them beneficial to jihadist groups, like IS and Al Qaeda. “We see that there is a climate of anxiety, fear and worry. Everybody is worried about the social and economic situation and with many people unemployed, this is a very fertile ground for radicalised groups to recruit members,” explains Bindner.

This could possibly be a long term effect, because from what Bindner has seen online, right now there hasn’t been a surge of propaganda or recruitment attempts during the lockdown. The fact that the economy isn’t doing well will have much more effect on radicalisation than the lockdown itself, she said.

An example is the current economic situation in Iraq which is already, having great difficulty. This economy is highly dependent on oil prices and weakened by the recent political crisis, risking a total collapse, which in its turn could lead to a new wave of recruitments for the jihadist insurgency of IS.

Vera Mironova, research fellow at Harvard University, has personally interviewed hundreds of IS fighters, including a 30-year-old man from Mosul whose trial she attended in 2018. He had only been a member of IS for the last three months of their occupation. His reason for joining? Supporting his family. They had completely run out of food and IS was paying him about 5 dollars a day.

The fact that the US-led coalition that had been supporting Iraq’s battle against IS has been drawing back their troops, leaving less than half the amount of troops a year ago from 5200 to 2500, has led to a decrease in pressure towards these jihadist organisations. On top of that the anti-IS coalition suspended the training of Iraqi troops to limit the spread of COVID-19 back in March.

“This decrease in military pressure provides them with a good opportunity and momentum to regain a sort of new health”, says Bindner.

Even though in the West a majority might think that Islamic State has been beaten, the narrative is far from over, says Bindner. “They have gone back from being in control of their self-proclaimed state, to being an underground insurgency and terrorist group. They still have money and they still conduct clandestine operations against Iraqi forces.”

The fact that the threat of terrorist organisations is far from over is confirmed when on the 21st of January 2021 Iraq’s capital Bagdad was hit with a twin suicide bombing, killing at least 28 people. The bombings took place at al-Tayaran Square of Baghdad, a busy commercial street in the heart of the city. Bombings like these have become relatively rare in the city. Still, this is not the first time this busy square has been targeted. Two years ago in January 2018, two suicide bombings killed 38 and left over a hundred people injured. IS claimed responsibility for the square bombings back then and although this attack has not immediately been claimed, suicide attacks have often been used by IS.

Enlarge

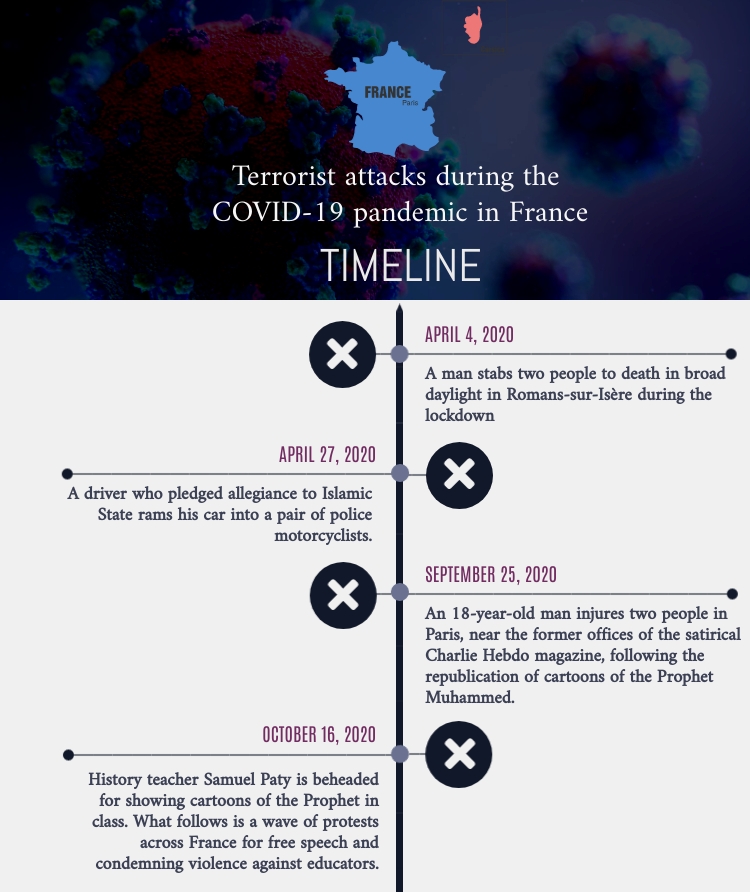

Does this mean that we need to worry about another surge in attacks on Western countries, despite the lockdowns? “I think that now it’s harder to plan large scale organised attacks, because there are no gatherings. At the same time it’s all a matter of opportunity,” explains Bindner. “If someone is radicalised and finds an opportunity, I think that the mechanisms that will put him into action can happen at any time. They will just find a way.”

Could young people be drawn to radicalism more during a pandemic, due to isolation and the increase in time spent behind a screen?

French psychiatrist Guillaume Monod, who has written a book on radicalisation and has spoken to many radicalised youth, doesn’t think so.

“Whether it be jihadism, extreme left or right, half of young people that radicalise, do this under influence of direct personal contact with someone they know. It’s not until that happens, that they start exploring these ideas online,” Monod explains. “Less than a quarter of radicalised youth, is influenced solely by social media.”

Furthermore, these organisations could themselves be hurting from the pandemic. Their lack of access to health care and refusal of strict health measures could weaken certain groups. “It’s complicated to predict the future.” says Bindner. “Authorities are doing their best to foil as many attacks as possible, but sometimes it comes in an unexpected way from people that are not being monitored.” But let’s not forget the words that satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo printed on their front page in 2011: l’amour plus fort que la heine. Love is stronger than hate.