Just outside the Romanian city of Cluj-Napoca, 1,500 people live near mounds of discarded clothing, tires, and metal objects. Children skateboard on litter-covered dirt paths, passing homes made of rotting wood with metal sheets for roofs. The so-called “environmental time bomb” is for many a source of livelihood, one they are determined to protect from closure.

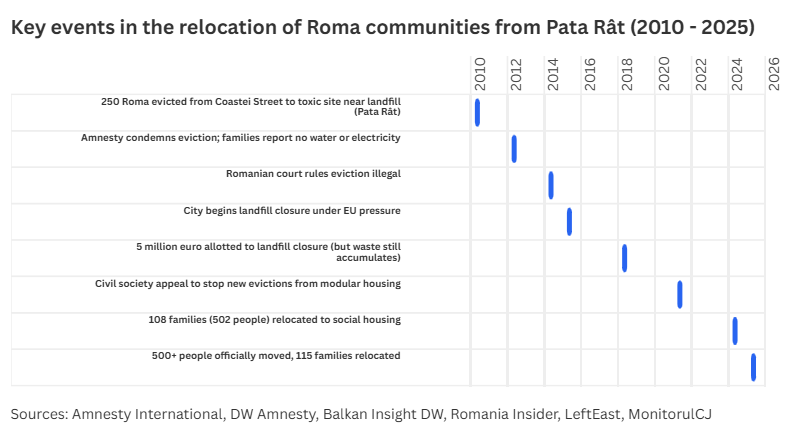

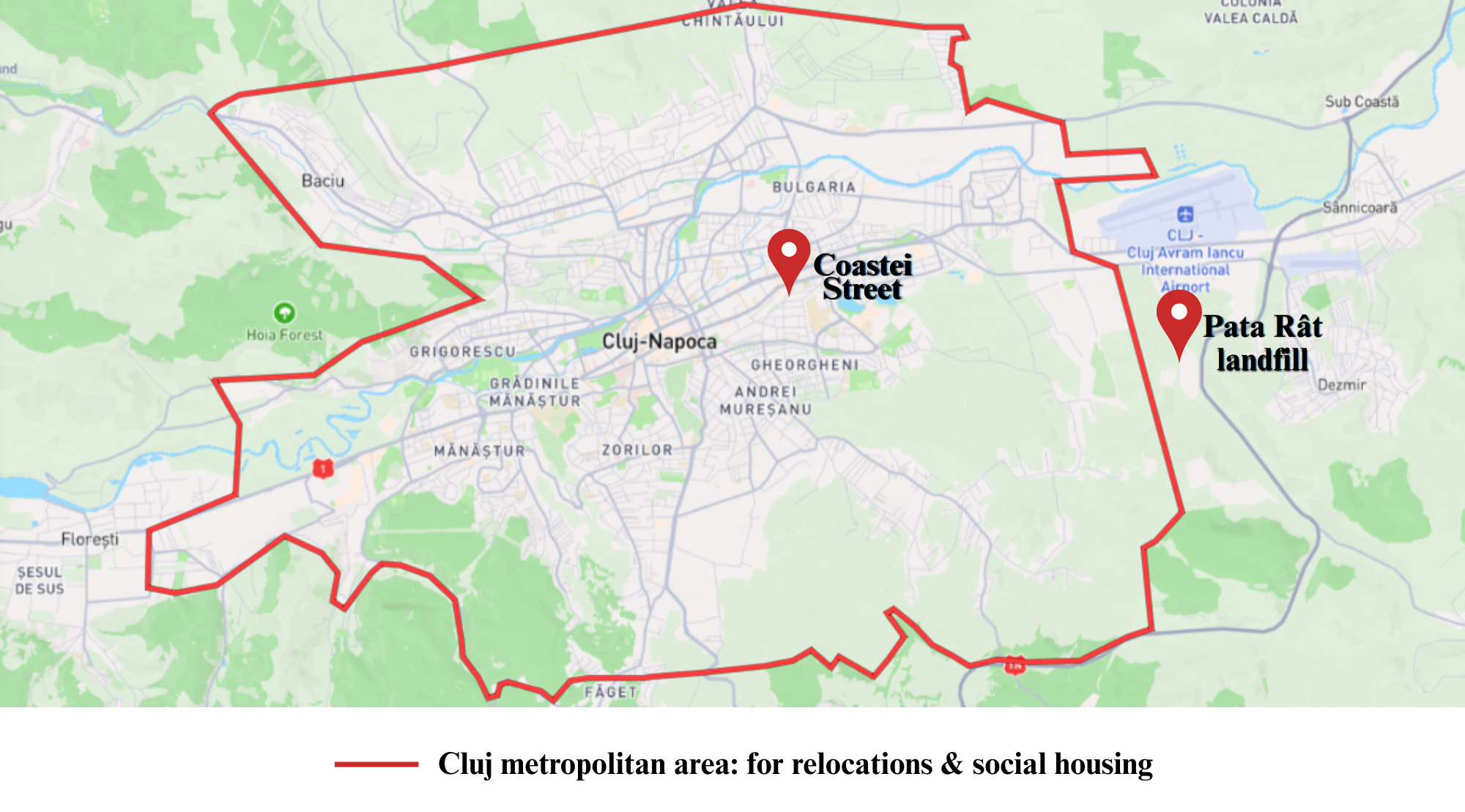

In the winter of 2010, more than 250 Roma were evicted with just two days’ notice from their homes on Coastei Street, a central location in Cluj-Napoca. Romanian authorities relocated them to Pata Rât, a site beside the city’s landfill and a former chemical dump. Some received improvised container homes. Others built makeshift shelters from scrap wood and corrugated metal. In 2014, a Romanian court ruled the eviction illegal. But none of the families received compensation.

Today, the city is trying to rewrite that history. Since 2024, Roma families have been moved from Pata Rât into social housing across the Cluj metropolitan area. The program is publicly framed as progress, funded by European Union and Norwegian grants, and supported by the city council. Over 500 people from 115 families have now been relocated. Mayor Emil Boc described the relocation as a “solidarity-based policy” in the local newspaper Monitorul de Cluj. However, housing activists and Roma residents see a familiar pattern: better conditions, perhaps, but exclusion all the same. On the other hand, some families don’t want to move out of the landfill, having their community there.

From a symbol of injustice to a showcase project

Pata Rât has long been a symbol of environmental injustice in Eastern Europe. Reports from Amnesty International and Deutsche Welle described the area as one of extreme deprivation: no clean water, sporadic electricity, poor sanitation, and ongoing exposure to toxic waste. Children developed respiratory illnesses, and adults struggled with depression and isolation. The site, still home to hundreds, is often referred to as a “ghetto by the dump.”

The current relocation initiative is meant to change that. Social housing units are purchased on the open market and scattered across the city’s periphery. Elderly residents are given priority in certain buildings. In the city’s public messaging, the program is described as a European inclusion model that reflects Cluj-Napoca’s ambition to become a “smart city” that leaves no one behind. But not everyone is convinced that the initiative is truly inclusive, or just another spatial rearrangement of exclusion.

A community long excluded

The Roma situation in Cluj reflects a broader pattern seen across Europe. Despite anti-discrimination laws and the European Commision’s EU’s 2020–2030 Roma Strategic Framework, Roma communities remain among the most excluded populations on the continent. Roma communities have faced centuries of systemic exclusion in Europe. Often stereotyped as nomadic or unwilling to integrate, they have historically been denied equal access to housing, education, employment, and healthcare. In Romania, as in many other EU countries, Roma have frequently been portrayed as either a “problem” to be solved or a group needing to be managed from a distance, socially and spatially.

Despite official EU strategies and funding mechanisms aimed at inclusion, these policies have rarely led to full participation. According to the European Commission, over 80% of Roma in the EU live below the poverty line, and many continue to face discrimination in public institutions and daily life. Segregated schooling, forced evictions, and informal settlements remain widespread, even in EU-funded countries like Romania. Because of this persistent marginalization, some residents of Pata Rât feel reluctant to leave. For all its problems, the settlement has become a place of identity, community, and shared experience, a rare space where they are not outsiders. Leaving Pata Rât doesn’t just mean getting a new address; it can also mean losing the only place where they’ve felt a sense of belonging.

Who really benefits?

For local government, the relocation serves multiple interests. It aligns with EU objectives for Roma inclusion, ticks boxes for international donors, and allows Mayor Emil Boc’s administration to present Cluj as a progressive, inclusive city. It also conveniently clears highly stigmatized settlements like Pata Rât, freeing urban space for development and real estate projects. Meanwhile, local media such as Monitorul de Cluj praise the program uncritically, often quoting City Hall without questioning the lived reality of the families involved. Stories highlight how many apartments were bought or how much money was spent, not whether relocated families feel welcome or safe in their new neighbourhoods.

Leaving the toxic environment of Pata Rât is a step forward. But for many Roma families, relocation has not brought full citizenship. It has brought plumbing, heating, and walls, but little assurance of dignity, participation, or long-term belonging. The city’s image may be improving. But unless Roma voices are centered in planning, the injustice of 2010 risks being repeated under a more polished name.