A hippo learning to swim. A whale befriending a cloud. Siblings turning their living room into an ocean. These were just a few of the short films shown at this year’s Kikeriki Children’s Shortfilm Festival. But the real breakthrough wasn’t on screen. It was in the room itself: a space intentionally designed for neurodivergent children to feel welcome. The question is: how can a film festival create spaces where neurodivergent children can participate without barriers?

From April 30 to May 25, 2025, Kikeriki presented a new kind of space. While the festival has existed for several years, this was the first time it offered consistent sensory-friendly measures specifically designed to welcome neurodivergent children.

The entrance to Kikeriki.

Neurodivergent children (those with autism, ADHD or other developmental differences) often experience the world in ways that are more intense or unpredictable. Noises, lights, crowds and sudden changes can feel overwhelming. That makes typical cinema experiences hard to access or enjoy.

At Kikeriki, that pressure was removed.

Mother and child at Kikeriki.

Each screening started off with a cheer: “Three, two, one, Kikeriki!” the children yelled in unison. It was loud and joyful and set the tone for what followed.

Lisa Mai and Christoph Schwarz, organizers of Kikeriki, moderating. A sign language interpreter is also present.

Children laughed loudly, called out questions, shifted positions, left for the Sause, an Austrian word for a snack buffet, or hugs. They were free to engage in the way that worked best for them. For many neurodivergent children, this kind of freedom is rare.

“We want children to come and feel like they don’t have to fit in a box,” says Lisa Mai, one of the festival organizers. “Whether a child needs silence, movement or closeness – our team tries to notice and adapt to that.”

Girl at the Sause.

At Kunstwerkstatt Tulln, the venue hosting this year’s festival, children were invited to arrive early. That extra time helped some of them feel more relaxed.

“We created a rest area because many children need breaks,” Lisa Mai says. “This helps them feel they don’t need to ‘perform’ or stay seated just to please adults.”

Children resting before the screenings start.

The need for this kind of space is clear. Nearly 2 in 100 children in Austria are diagnosed with autism, according to the Austria Center Vienna.

For families with children on the autism spectrum, sensory challenges are often the biggest barrier in cultural spaces.

Cussions on the floor.

Loud noises, unpredictable crowds and unfamiliar routines can make outings overwhelming. A 2022 study in Curator: The Museum Journal (Hladik et al.) highlighted how these sensory difficulties often limit participation in cultural activities.

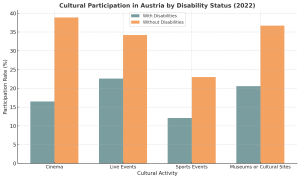

Supporting this, a 2022 study by Statistik Austria found that only 16.5% of people with disabilities attended the cinema at least once in the past year, compared to 38.9% of those without disabilities. Cinema showed the largest gap in participation among all cultural activities. Similar trends are seen in concerts, theater and dance events.

Statistik Austria (2022)

During the screening of a shortfilm.

That’s where Kikeriki comes in.

“We talked to colleagues, to parents, to organizations, and, most importantly, to people with disabilities themselves,” Lisa says. “We also received critical feedback. That was important. The program didn’t come out of nowhere.”

Behind the scenes, the shift took time. It also took staff training, long meetings and careful planning.

What it didn’t have: formal funding.

“We’ve had to get creative,” Lisa says. “There’s passion but a lack of formal funding structures that prioritize accessibility.”

The screenings themselves were well attended. But some of the more specific accessibility offers, like the chance to explore the venue before a screening, were used by only a few families.

“New things always need time,” Lisa notes. “People need to hear about them and to trust that they are truly welcome. We want to build that slowly and carefully.”

Children watching a shortfilm at Kikeriki.

Kikeriki is part of a small but growing movement in Austria. Vienna’s Filmcasino, for example, offers sensory-friendly “Für Alle” screenings, with lower volume, dimmed lights and a relaxed policy on movement and noise. The Viennale film festival has improved access too, with wheelchair seating, hearing systems, and audio descriptions for selected films.

Internationally, projects like Inclusive Cinema (UK) and the Swiss-German FASEA Project are developing tools (from sensory kits to captioning apps like Greta and Starks) to make filmgoing more accessible for neurodivergent audiences.

In Austria, these practices remain rare.

After the screenings the children were invited to paint their favourite shortfilm.

“We need to stop treating inclusion as optional,” Lisa says. “The model is there. What’s missing is the commitment.”

For neurodivergent children, the environment is often the difference between participation and exclusion.

“It’s not about fixing children,” she says. “It’s about fixing the environment.”

Photos by Julia Kaffka (May 25th, 2025)