Implementing the guidelines of a government appointed committee would make the Netherlands a global pioneer in the restitution of looted art from the colonial era. But for countries like Indonesia, it takes more than the simple return of 100,000 objects to undo historical injustice. Equal cooperation is needed.

190 years it took for the dagger of Indonesia’s national hero Prince Diponegoro to return to his homeland. As leader of the rebellion against Dutch colonial rule, he was taken prisoner during the Java War in 1830. In 1975, Dutch and Indonesian experts agreed to return cultural goods associated with historically significant figures to Indonesia, but it was not until 2020 that the Museum of Ethnology in Leiden finally found the “Kris” in its collection.

Recently, however, the debate over the repatriation of objects stolen during the colonial era has gained momentum, starting with researcher Jos van Beurden’s doctoral dissertation “Treasures in Trusted Hands: Negotiating the Future of Colonial Cultural Objects”. In 2019, the Dutch National Museum of World Cultures (NMVW) was one of the first museums in Europe to introduce its own guidelines for countries wishing to claim stolen art or an artefact of significant cultural importance. About 40% of the 450,000 objects in its collection are believed to come from former Dutch colonies. “The interesting thing in the Netherlands is that the NMVW and the Rijksmuseum, which are the two major ethnographic art and history museums, they are pushing for changes. My impression is that it’s more than symbolic and that at least the NMVW is really preparing to let objects go,” says van Beurden. But the effort had one crucial flaw: Because it is a state collection, the final decision rests with Culture Minister Ingrid van Engelshoven.

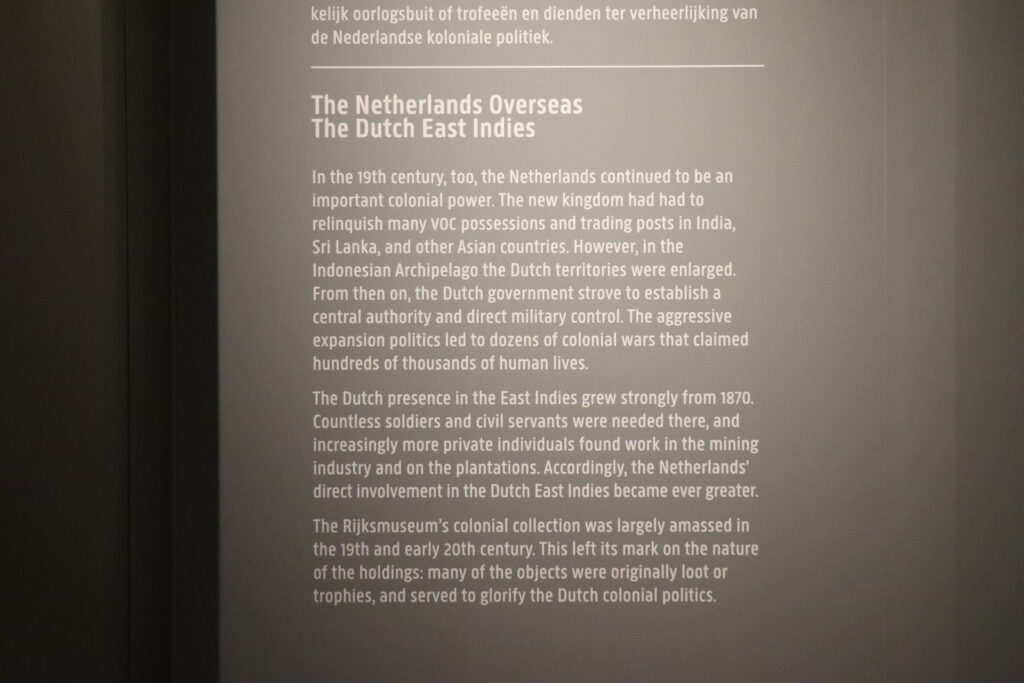

Founded in 1800, the Rijksmuseum, with more than 8,000 exhibits the largest museum in the Netherlands, is on the bucket list of many Amsterdam tourists. About 2.2 million visitors are welcomed here every year. But behind the façade of this building, which appears beautiful at first glance, dark stories are hidden. The poster announces the new exhibition, which focuses on slavery during the 250-year Dutch colonial period.

“Groundbreaking” guidelines

She, in turn, appointed the Gonçalves Committee, which was tasked with outlining a future national policy framework for the handling of colonial heritage. The resulting guidelines, published in a report last October, are what van Beurden calls “groundbreaking”. The document calls for a “recognition that an injustice was done to the local populations of former colonial territories when cultural objects were taken against their will” and recommends the unconditional return of these artefacts to the former colonies if requested. This could apply to more than 100,000 objects, mainly from Indonesia and Suriname. To examine whether provenance investigations provide “sufficient evidence” that an object was acquired involuntarily, the Dutch government now wants to set up an independent assessment committee. No other European country has gone this far yet, but for Indonesian historian and curator Sadiah Boonstra it is the decisive step towards coming to terms with the past: “The returning of objects and object restitution to me is really about rectifying those historical injustices and trying to undo what has happened in the past in order to create a more equal future and to undo the coloniality of museums and of society today.”

However, it is highly unlikely that thousands of objects will now suddenly be returned to Indonesia in one fell swoop. Each item has to be examined individually for its origin and provenance research takes a long time. A pilot project of the Rijksmuseum, the country’s largest museum, and the NMVW, for example, which is studying 25 selected objects from Indonesia and Sri Lanka in order to develop a methodology for researching the provenance of collections with a colonial context, is designed to run for three years. “What I miss in the report and in the policy advice is some kind of operational guidelines on how we can speed up provenance research. It could have been something like a general pardon for objects that we are almost certain are war booty,” says van Beurden.

But there are also numerous traces of this period in the permanent exhibition. Only one room, “The Netherlands Overseas”, speaks openly about this. You suddenly see the museum with completely different eyes, and an uneasy feeling comes over you when you realise the cruel conditions under which many objects came into Dutch possession.

Missing puzzle pieces of the past

But for Indonesian historian Bonnie Triyana, who gave advice to the Goncalves Committee on behalf of his country, “not only the objects are very important, but also the story behind the objects.” None of them should return without it, not like the 1,500 artefacts that were given back to Indonesia in 2020 after the closure of the Nusantara Museum in Delft. For with the stories comes knowledge that could help both Indonesians and Dutch better understand their own history, especially in terms of historical injustice. “There are many missing links in Indonesian studies, especially because of the unavailability of artefacts,” says Indonesian historian Sri Margana, who is Professor of early modern Indonesian history at Leiden University. Triyana adds: “We are not the rubbish bin. Hopefully only the meaningful objects for our history will return to Indonesia. There is a young generation, not only in Indonesia but also in the Netherlands, who is now starting to ask questions about what happened in the past. Colonial objects can be the light that brings us to the past.”

For this to happen, it is important that Indonesia can decide for itself which objects are to be investigated, says van Beurden: “The former colonies should be encouraged to take the lead in setting priorities for provenance research.” This is the only way to continue the co-production under which the guidelines of the Gonçalves Committee with its diverse members were created. Indonesia has now formed its own committee to advise the government on the return of the objects and to conduct research, in which Margana and Triyana are also involved. They are still waiting for the official announcement by the Indonesian government, but Triyana already knows one thing: “The Indonesian committee will seek any possibility that we have to collaborate with the Netherlands.”

The very first sentence under the infamous “Benjarmasin diamond” reveals how the 36-carat piece found its place in the exhibition: “This diamond is war booty.” The stone once belonged to the Sultan of Banjarmasin (now the Indonesian part of the island of Borneo). In 1859, Dutch troops conquered the sultanate and violently abolished it, taking the diamond with them.

Cooperation on equal footing key

That he would like to see cooperation on an equal footing is something Triyana emphasises many times during the conversation: “We are seeking equal cooperation with the Netherlands, not an unequal cooperation between a former colony and the colonizer. It should be an equal cooperation between two countries, involving many researchers of both countries to produce knowledge and history.” Triyana sees it as a good “starting point” that Indonesian and Dutch museums have maintained close and, as he says, “friendly” contact for many years. He himself has been a guest curator at the Rijksmuseum since 2018. Recently, the Rijksmuseum, together with the Free University of Amsterdam, announced a new five-year research project to take a close look at the colonial collections of five Dutch museums – Gadjah Mada University and the National Museum in Jakarta are also to participate.

It is important that Indonesian students have the opportunity to go to the Netherlands to gain more experience in provenance research, says Boonstra: “We are a bit behind on that, also because the access to the collections that actually involve colonial objects is different than for researchers in the Netherlands. Even if we had digital access, you also sometimes just really need to be with the physical objects and include that in the research.” Indonesia is therefore in the process of setting up scholarships, also to train museum staff and thus compensate for possible deficiencies in infrastructure. Margana: “We have realised that our infrastructure, our museums, our institutions, which will be the new hosts for the artefacts, need to be renovated.” Still, it upsets him that people cite this as a reason to keep colonial art in the Netherlands. “We’re very serious about it. That’s why we are spending a lot of money to give a grant to the people who will study how to handle museum conservation and all kinds of museum management to guarantee that the objects come to Indonesia in safe hands, in safe conditions.” Here, too, Boonstra insists on the support of the Netherlands: “If it is decided that a certain number of objects should go back to Indonesia and the infrastructure is not in place, that should also be solved together. It cannot just be the responsibility of Indonesia.”

This painting by Nicolaas Pieneman, completed in 1835, shows the arrest of Diponegoro by Lieutenant-General Baron De Kock from a Dutch perspective. Prince Diponegoro was the most important Javanese leader in the Java War (1825-1830). Although the Dutch promised him safe conduct, he was arrested during the peace negotiations. He owned the kris, which the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden returned to Indonesia in 2020.

Many questions, few answers

But many questions remain unanswered, such as who will finance the repatriation of the artefacts. A particular challenge, especially in the Indonesian context, will be to clarify with whom the objects will remain once they are back in their country of origin. A 36-carat diamond, for example, was looted by Dutch troops in 1875 from the Sultanate of Banjarmasin, now part of Indonesia on the island of Borneo. Although the Gonçalves Report treats the restitution as a state-to-state matter, descendants of the sultan have already claimed to be the rightful owner. “Most of the artefacts come from families, kingdoms and individual communities. If we don’t sort out this problem first, it will bring a very chaotic situation in Indonesia,” says Margana. Van Beurden: “The reality is that states are often colonial products, like Indonesia. The report is not very courageous in this respect. Of course, there is a risk that we will be accused of neo-colonial behaviour if we say, Indonesia, you should do it differently, but at the same time we should look for ways and encourage, for example, a number of like-minded countries to hold a South-South conference and have a dialogue on how to deal with minorities.” Triyana disagrees: “How we deal with the objects once they have already returned to Indonesia will be our business.”

And then there is the question of what happens to artefacts that have not been stolen or lack evidence. Here, the Gonçalves guidelines do not provide for unconditional return. Instead, the Netherlands is allowed to make a claim itself, and Margana is worried that they will make use of this right. Over the years some of the objects have also become valuable assets for the Dutch, such as the manuscripts kept in the library of Leiden University: “Not all institutions in the Netherlands will give artefacts back to Indonesia easily.”

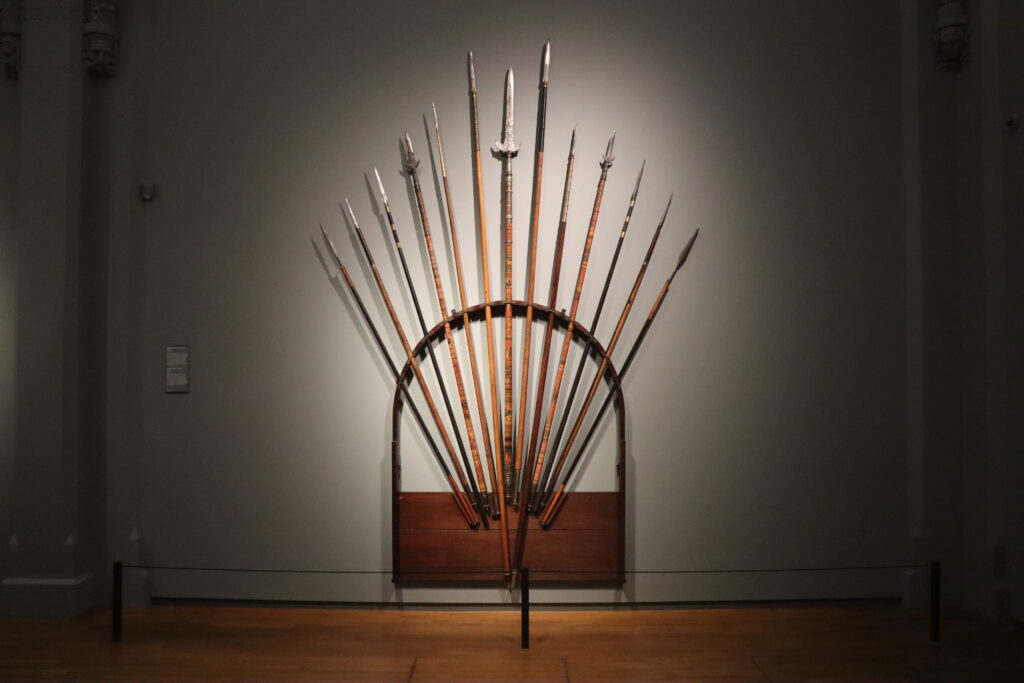

The spears seen here were not stolen, yet the Netherlands came into possession of them under unequal power relations. J.C. Baud, Governor General of the Dutch East Indies, received weapons, traditional symbols of power, from local rulers as a token of their extorted loyalty to the Dutch government during an inspection tour in Java. The Java War claimed 200,000 victims on the Javanese side, 15,000 on the Dutch.

Time to turn words into deeds

How this will play out in reality remains to be seen, but all parties agree that it will be a long process that could take decades. While the Minister of Culture has already given her approval, the Dutch Parliament has not yet adopted the new policy framework. In the meantime, Germany has become the first country to announce that it will hand back the Benin bronzes looted by British troops in 1897 to Nigeria. The Netherlands, ahead of the European pack in terms of approving the creation of a commission to evaluate claims, would still have to assess the handover of Benin bronzes in Dutch collections, slowly falling behind in terms of actual restitutions.

Nevertheless, Triyana has confidence in the process: “I see good will of the Dutch government, but of course we are still waiting for the next step of this good will.” Boonstra too believes that there is no turning back now: “Now there is an advice that the government needs to relate to, no matter what. It’s not something that they can just push aside. At this point in time, the genie is out of the bottle.” Now, according to van Beurden, it is up to the Netherlands to take the next steps: “Colonialism has violated a lot of trust between colonisers and colonized. We have to take a number of trust building measures in order to make the other side believe that it is serious, that we really are willing to return these things.”

All the exhibits on this table were stolen from the Indonesian island of Lombok. They are only a fraction of the 230 kilograms of gold, 7000 kilograms of silver and countless precious stones that Dutch troops took from the royal palace in 1894. In 1977, a large part of it was returned to Indonesia.