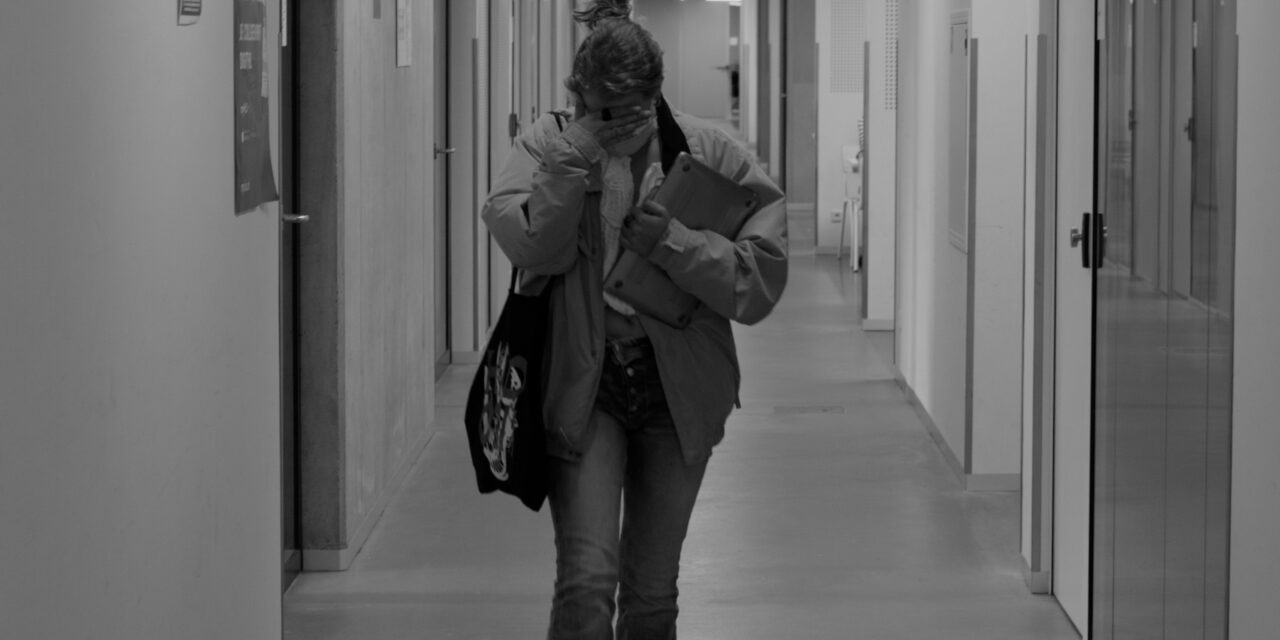

“Looking back at it, it feels like the whole time is just one big blur” says Hannah while she waits for her coffee in a sunny café, “it did not matter what day or what week it was because they all felt the same. I couldn´t tell you if some of the things I did were in November or in February because looking back at it they all feel the same.”

This is a feeling that is very common among young people. The last months are felt as an indistinguishable mass of online events and varying degrees of isolation. A time that has taken its toll on many members of society especially in regard to their mental health. Some -like Hannah- have started to struggle with depression, others with feelings of anxiety, despair, loneliness and a worsening of pre-existing mental health problems. Amongst young adults alone the amount of people who report struggling with mental health has almost doubled, taking a silent toll on people´s health in a time in which health itself appears to be the primary concern of the public. And while for most people the end of lockdown and the gradual return to a normal life should bring significant improvements in their condition there is a sizable minority for which this return brings new challenges.

This predominantly applies to people who are more prone to mental health disorders in general and who have more of an introverted personality. Something which has “helped” them to cope with lockdown but is now hindering their efforts to readjust back to a more social environment. Especially if they have developed anxiety or feelings of exhaustion and lack of motivation or even depression the return to a normal life can be a stressful and exhausting experience. And most importantly one that is going to take significantly longer for some than it will for others. An important part of this is that after fifteen months of being told to isolate, to get tested regularly and of being bombarded almost daily with infection rates and numbers of covid-19 related deaths, the fear of covid might take longer to vanish then the actual threat projected through the disease.

This feeling has now even been given a name by psychologists: Covid-19 anxiety syndrome. It basically describes the fear people experience of contracting covid themselves as well as the fear of infecting their loved ones. This in turn comes with a fear of situations in which these things might happen even though more and more people are being vaccinated. Large crowds for example in whom it isn´t possible to stay one and a half meters apart from one another or confined spaces like classrooms in which people are being taught in close proximity to each other without having to wear face masks. These situations, while being an enormous relief for many, can take a serious toll on others.

This isn´t helped by the state of the Dutch mental health system which psychologist Laurens Nijhuis describes as “extremely overburdened”. Patients often have to wait for months before they are able to get treatment and even appointments with student counsellors or student psychologists which should be the first places young adults can approach when they feel like they are starting to struggle can take weeks to arrange. There are even reported cases of patients concretely struggling with severe depression and suicidal thoughts who had to wait for more than half a year before they could see professional help. A condition Laurens describes as inexcusable.

However, there are things schools and universities can do and some have done to improve the situation at a relatively low cost. Simply hanging up posters or including information material about mental health in an introduction week can already help somebody who is struggling by reassuring them that they are not alone and most importantly that struggling with mental health is OK. And not a sign of weakness.