After more than twenty years of intense negotiation, on June 28, 2019, the European Union signed a free-trade agreement with the MERCOSUR, an economic bloc formed by Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Even though the Agreement is yet to be ratified by the European Parliament and Commission, it is a diplomatic landmark, as it will cover two markets that represent more than 750 million people and around 25% of global GDP.

However, like most major international negotiations, the EU-MERCOSUR deal is surrounded by polemic and controversies.

The main argument used by those who oppose the deal is the lack of serious and robust environmental protection policies in the region, especially when it comes to Brazil, the biggest economy and the largest country in South America.

In favour of the deal, supporters say that it will increase cooperation between the two blocs and, therefore, facilitate MERCOSUR countries’ development, which will consequently stimulate their environmental targets and improve their preservation standards.

As forementioned, Brazil, due to its size, biodiversity, and natural richness, is one of the central actors not only in the negotiations of this trade deal but in the global debate about climate change and other environmental issues. Despite having such importance, in the past years, environmental laws and protection bodies in Brazil have been changing, and not always for the best. Indigenous rights have been often attacked by the national government, IBAMA (Brazilian Institute of Environment) and other bodies responsible for natural surveillance and protection have been constantly defunded, laws to facilitate mining and deforestation have been proposed, etc.

How do Europeans see this shift in environmental protection in Brazil? What impact does it have in the negotiations of the trade deal? And how do indigenous peoples, whose lives directly depend on the environment, experience this environmental agenda?

A bad deal?

Anna Cavazzini (Green Party), Member of the European Parliament, Vice-Chair of Brazil Delegation, and Chair of the European Committee on Internal Market and Consumer Protection, is one amongst those who oppose the deal.

According to her, the current Brazilian government is the biggest responsible for the deal not to be fully in place already. “I think if the Bolsonaro government hadn’t dismantled all the environmental protection, defunded basic environmental agencies, and weakened the rights of indigenous people, the Mercosur-EU deal would’ve been probably already done.”

Ms Cavazzini also mentioned that there is much interest in the European side to approve the deal, and “if it wasn’t for Bolsonaro’s very bad track record on the environment, we couldn’t have organised an opposition. He made it very easy for us to oppose the deal”.

For Ms Cavazzini, Brazil’s environmental agenda and agricultural practices are the main reasons for the deal not to be ratified. There are numerous concerns involving the industrial model of agriculture practised in South America, which does not follow the same standards and regulations as the European Union regarding food quality, animal welfare, environmental impact, etc. This model “has destroyed a lot of the rainforest” in the past years, and “the Mercosur deal is celebrating this destructive model of agriculture”.

The Vice-Chair of Brazil Delegation emphasised that her party, or other Europeans who oppose the deal, are not purely “against more trade with Brazil or the Mercosur countries”, as more trade is always positive, but they have to “ensure the deal doesn’t lead to more environmental destruction and deforestation”.

A possible solution, according to Cavazzini, would be a renegotiation of the deal. “A U-turn” from the Brazilian government in many areas would also be positive, not just for the deal, but for the country’s relation with the EU as a whole, as she said: “the Bolsonaro government really needs to take back all the laws that are on the table of the Congress, all the laws that involve scrapping indigenous rights, for example. The government needs to put in place really strong Human Rights and Environmental policies, then the relation would get a little bit better, but I don’t see that happening at the moment, I doubt it.”

A ‘win-win situation’?

Jose Manuel Fernandes (European People’s Party), Member of the European Parliament, and Chair of Brazil Delegation, on the other hand, is a supporter of the deal.

“I hope it will be ratified!”

For Mr Fernandes, “environmental arguments are often used to hide protectionism, because there is a fear that European farmers will not be able to compete with products coming from Brazil and other MERCOSUR countries”. But there is also a political argument used by those who are against the deal, “in Europe, many oppose the deal because they believe that, by ratifying it, they would be giving Bolsonaro extra political strength for the next elections”.

However, for Mr Fernandes, approving the deal would bring closer two regions with “the same values, that have to be reinforced, such as democracy, freedom of religion, the intransigent defence of human dignity, the rule of law, workers protection, the necessity of preserving the environment in a sustainable way, those are the values we share and have to base our economic policies on”.

“It is essential, in a world with potencies who do not abide to these same values, that those who do, unite and cooperate.”

The Chair of Brazil Delegation said “the deal would give both the EU and MERCOSUR more geopolitical power”, and that “the key word in this scenario is COOPERATION, nobody is here to lecture anyone, or to have paternalist attitudes”.

Mr Fernandes also stated that “the deal is a win-win situation for both sides”.

For him, “the environmental argument is valid, but we cannot admit that it becomes a pretext to hide other arguments”. To conclude, the MEP said that the environment will probably cease to be an issue soon: “at the COP26 in Glasgow, Brazil has signed many agreements, and has compromised to end deforestation by 2028 and be carbon-neutral by 2050. This is positive, and there are signs that environmental issues are soon to be removed.”

A local perspective

Karo Munduruku, an indigenous leader from Itaituba, northern Brazil, gives a local perspective of how the Brazilian government has been dealing with the environment and indigenous peoples, how Europeans could help, and why it is so important to protect those natural areas.

According to him, the current relationship between his people and the government “is always one of distrust”, and that politicians only come to their village during electoral campaigns, otherwise, their voice is only heard, and the environmental agencies only act, when there “is a demonstration or protest, demanding preservation”.

Karo said that “with this current government, things got even worse”, instead of assigning competent people to deal with his people and their issues, the government “put in charge military personnel, who do not have the capacity to understand what environmental preservation is”.

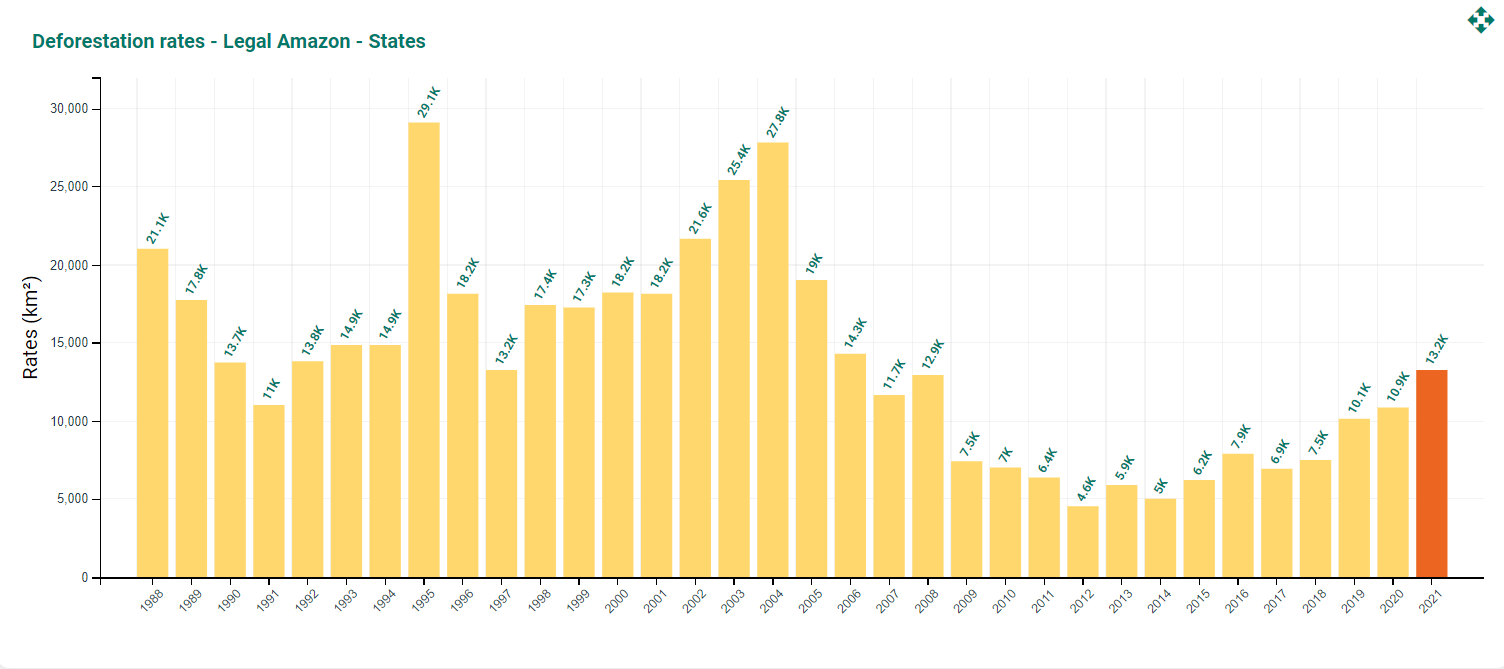

As the graph indicates, deforestation in the Legal Amazon region has been on the rise in the past years, with 2021 having the highest deforestation rate in the last 14 years, 13.235 km2, 21,97% more than in 2020. (Source: PRODES)

The indigenous leader also stated that Europeans should change the way they deal with matters of preservation in the region. “They need to set an example of preservation. It’s no use saying that you’re going to donate billions to Brazil to preserve, if they don’t use it for preservation. Some countries don’t have anything left to preserve, because they have destroyed everything, so they donate billions to Brazil so they can continue with their status of developed countries.”

To conclude, Karo Munduruku explained the obvious, the reasons to protect indigenous peoples, their lands and nature: “To preserve forested areas is to preserve life, history, culture, and tradition of those who live and survive from the environment. 520 years have passed, and the indigenous lands are the only ones that remain preserved, while other areas no longer exist.”

To ensure the preservation, there must be general cooperation, because “the indigenous peoples already do it (preserve), the riverside communities do it as well, but if it’s just us, it’s pointless”.

Conclusion

The EU-MERCOSUR trade deal is a complex and controversial negotiation. There are many things on the table, but the environmental aspect is, undoubtedly, the most important of them.

If the EU wants to praise itself as a beacon of natural preservation, fight against climate change and sustainable development, it must not sign a deal that will legitimise current Brazilian (lack of) environmental policies and effort and the South American predatory model of agriculture.

Regarding Brazil, unless a profound shift in the government’s environmental agenda happens and the current situation changes, the EU would be showing its hypocrisy if they fully ratify the agreement without further preservation demands. The natural, social and political consequences of such action may be unpredictable.

Cooperation is of course the key solution for the deal and the environmental problems, but our world, and our future, demand that preservation must be the priority, and supporting, by trade deals, countries and practices that go against this agenda shows remarkable incoherency.