Recently, a Chinese streaming platform, Tecent Video, edited out the ending of Fight Club (1999).

In the Tecent version, the iconic final scene, (spoiler alert!) in which Tyler’s (Brad Pitt) Project Mayhem is put into practice, detonating bombs in multiple buildings where credit records were held and sparking a revolution, was cut out and replaced by a black screen with the following caption, in a clear effort to make it less transgressive: “Through the clue provided by Tyler, the police rapidly figured out the whole plan and arrested all criminals, successfully preventing the bombs from exploding. After the trial, Tyler was sent to [a] lunatic asylum receiving psychological treatment. He was discharged from the hospital in 2012.”

According to Taynã Puri, CEO of Hollywood Film Academy, even though this so-called censorship of Fight Club isn’t justified or right, it’s understandable:

“Despite questioning the system, Fight Club still does it through an ‘US-centred’ perspective, and raises a debate about the capitalist Western way of life. Therefore, it can be, in a certain way, seen as an ideological influence which doesn’t match the one predominant in China.”

Enlarge

However, changes like the one Fight Club suffered isn’t something new or isolated. Studios and platforms changing their productions or promotion material in certain countries to better adapt to the local audience or government is a fairly common phenomenon, and weirdly enough, it seems to follow a tendency of excluding women or minorities.

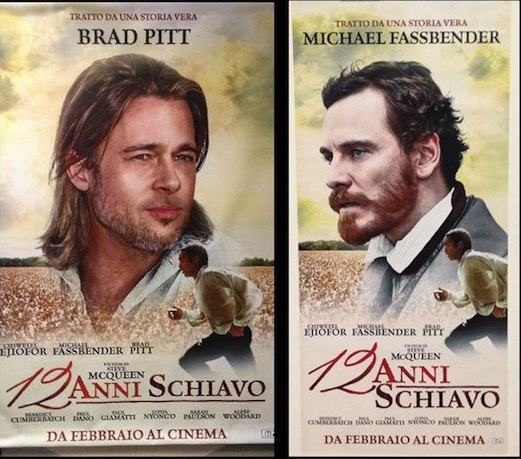

Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2016) Chinese poster had black actor John Boyega’s character downsized by more than 50% — the same happened with Felicity Jones’s character in the Star Wars: Rogue One (2017) poster. Something similar was seen when the Italian version of the 12 Years a Slave (2013) poster highlighted Brad Pitt and Michael Fassbender at the expense of Chiwetel Ejiofor, the black actor who played the main character in the film.

But, Taynã Puri doesn’t consider it censorship, and says these ‘marketing choices’ are less important than the message the actual film brings:

“If the film brings the right message and the minority characters are represented in a good way, in a manner which the public can see their importance to the story, this marketing stuff is a matter of less relevance.

“It’s not something that we, film-makers and cinema lecturers, give much attention, as long as the films and their stories get to people.”

But would there be any case in which censorship in cinema would be justified?

It may come in many ways, through banning, editing parts, etc, and, as Taynã Puri says, censorship is inherently unjustifiable, but in one scenario:

“Censorship is only acceptable with productions that can potentially put a determined group or individuals at risk, especially those who were historically marginalised, such as people of colour and women.

“Of course some films should have age-limitation to protect kids from being exposed too early to a certain content, but there shouldn’t be any other form of ‘censorship’ in any kind of art or expression. Therefore films which perpetrate authoritarian, intolerant, nazi-fascist and/or racist ideals, like The Birth of a Nation (1915), should be the only ones being silenced and prohibited by governments, for the sake of our democracy.”

Enlarge