After the fires in Europe’s largest refugee camp Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos, tens of thousands of citizens all over the continent took to the streets demonstrating for a fundamental change in the EU migration policy. Yet, Matthias Mertens, co-founder of ‘Europe must act’, a grassroots movement of volunteers based in Greece, doesn’t believe the “inhumane” living conditions in the camps will disappear with the new ‘Pact on Migration and Asylum’.

On the 8th of September fires destroyed Europe’s largest refugee camp Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos, leaving almost 13,000 people without shelter. This was just the tip of the iceberg. Originally designed to accommodate 2,800 people, the vastly overcrowded site had been failing to cover the most basic human needs for years. According to the Aegean Grassroots Report, which gives an overview of the humanitarian crisis from the perspective of NGOs and refugees, it was lacking in safe drinking water, adequate sanitation facilities and durable housing. Residents had to spend up to three hours queuing for each meal.

In Utrecht around 600 people took part in the peaceful protest at ‘Jaarbeursplein’ located next to the Central Station.

In March 2020 in response to the ever-worsening situation on all the Greek islands ‘Europe must act’ was established by local grassroots NGOs to campaign for the “humane, dignified and legal reception of refugees”. Co-founder Matthias Mertens explains: “They are really small organisations that were set up by regular people who just saw the situation and thought they needed to do something. You see this on the islands, but you can also see this in the rest of Europe. They are everywhere because everywhere governments are not doing what they are supposed to do. They are neglecting, they are ignoring this extremely vulnerable group of people who under international law have rights and these rights are being denied to them. Citizens act because governments don’t.”

The Netherlands has agreed to take in 100 refugees from the Moria camp on Lesbos, 50 of them being unaccompanied minors under the age of 14. “100??! Two zero too few!”, says the sign of this boy.

9,000 people have now been moved to a new, supposedly temporary camp on the island of Lesbos. Even though Ylva Johansson, EU Commissioner for Home Affairs, stated there would be “no more Morias”, in the eyes of Matthias Mertens “Moria 2.0” has been created: “The tents are too close to the water and exposed to cold winds that come from the north in winter. They are not made to cope with such weather. Another concern is that the tents are put too closely together. If there were to be another fire in this camp, for people to evacuate would be extremely difficult. The basic idea of the camp, of concentrating people in one place is the same.”

“Help refugee children now”, this boy is demanding.

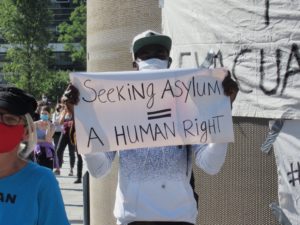

Last Sunday thousands of protesters in 27 cities across Europe, such as Berlin, Paris and Madrid, came together demanding European governments to immediately evacuate all camps on the Greek islands. “The Moria fires have shaken up people a bit, have drawn in more people to realize that something needs to happen”, Mertens concludes.

Organisers made sure the event followed Covid-19 guidelines by drawing crosses on the ground for participants to stand on.

On Wednesday the European Commission proposed its long-awaited ‘Pact on Migration and Asylum’ which was presented as a “fresh start”, but the co-founder of ‘Europe must act’ is convinced that very little will change: “It puts strong borders over the rights of refugees. It does not give any guarantee that the camps will disappear or that the inhumane living conditions in the camps will be something of the past. Its intention is to create solidarity among European States, but it rather is solidarity in pushing people out than actually taking people in. One example of this is ‘Return Sponsorship’, which is seen by the commissioners as a form of mandatory solidarity. Countries are obliged to help other countries with deporting asylum seekers whose claims have been rejected.”

The protests running under the banner “We have space” and “No more Morias!” were organised by ‘Europe must act’ and ‘Seebrücke’, a German organisation campaigning for the establishment of safe routes for refugees and the decriminalisation of sea rescues.

What the ‘Europe must act’-movement has been calling for is solidarity in relocation, which means European states would take in asylum seekers from the border countries. This is also included in the pact, but no numbers are mentioned that each state has to take in. Instead the countries are given a choice between returning and relocating people. Matthias Mertens is concerned there will be “a mismatch between the people who are recognized as refugees and who are then able to go to another European State”.

In the future, arrivals from countries with a recognition rate lower than 20% will be sent to a fast-track border procedure and within twelve weeks a decision on an asylum application is to be made at the external border. “If all these procedures are sped up this much, mistakes will be made and people will not have a fair hearing of their asylum claim”, Mertens believes, adding that people will still need a place to live during this period.

For him the only “sliver of hope” is a community-sponsored relocation system mentioned in the pact, but the Commission has not yet gone into detail. “Another demand that we have is having a municipal reception system or at least giving cities and towns across Europe a greater say in relocation and integration of refugees because among cities there is a high willingness to actually do this. There is also much more understanding of what it means to welcome refugees into a community. It can create a positive dynamic in the city.”

After meeting Ylva Johansson in reaction to an open letter published by ‘Europe must act’ back in March, signed by 160 grassroots NGOs, 100,000 individuals and ten members of the European Parliament, Mertens realised: “We can scream and shout all we want at the EU-level but the real change will need to happen on the level of nation states, because they are the ones who are blocking the proposals for solidarity-mechanisms.”

Even though the activist is hoping for a structural solution, meanwhile there is still a high demand for financial and technical assistance, one example being psycho-social support: “Besides the humanitarian crisis, there is also a mental health crisis going on here. There are a lot of people with posttraumatic stress disorder because they have been through horrible things in their home countries but also here. There is some psycho-social support available but as any other service, be it education, be it legal aid, they are overwhelmed and working at maximum capacity, having long waiting lists.”

“To really understand what is happening here, you have to see it”, Matthias Mertens believes. “These people in Brussels live in a completely different reality because what they put on paper maybe looks nice in an office, but we just know from experience that what is on those papers is not going to solve the problem. Here the suffering will continue.”