I am in the city of Gdansk, Poland. It is my first time in this country. It is December, so it is cold, but very very cold and the snow doesn’t seem to stop.

But why am I here, what has brought me to this country?

One thing that has always struck me about Poland is its “conservative worldview” in the eyes of the gallery, in this case in the eyes of Europe. One day I read a headline in the European Parliament press that particularly caught my attention: “Poland: attacks on media freedom and the EU legal order need to stop”. Such a headline is not likely to leave anyone indifferent, least of all a student of journalism.

Poland is a parliamentary republic whose media are repeatedly penalised and controlled in a way that calls into question their credibility. In 2021, the political sector wanted to implement the “Media Control Act”. And it was at that moment that journalism in Poland received a direct attack on its professional ethics: social and moral freedom.

That is why, in this investigative report, I am going to interview two journalists living in Poland and ask them to explain their experience and their point of view on this situation.

On the one hand, there is Anna Rzhevkina. She is a freelance journalist based in Gdansk (Poland) for 10 years now. She covers business, economics and human rights with a focus on Central and Eastern Europe.

“I moved from Russia to Poland because Reuters media agency offered me an opportunity I couldn’t leave behind. However, Poland is not the best example of freedom of expression as far as the press is concerned,” Rzhevkina tells me.

On the other side is Arnout Le Clercq, a freelance correspondent who covers news from both Central and Western Europe.

“To understand how Poland has come to this point it is necessary to understand the drastic changes at the political level in which the power of the media has played an important role in shaping the country’s history,” says Le Clercq.

Historically, Poland was a socialist state from 1945 until 1989, when it was called the People’s Republic of Poland, and when the regime fell that year, the changes touched the media, says Álvaro Marcos Blanco in his research “Audiovisual Regulation in Poland”. In fact, thanks to this event, it has been possible to understand to what extent the media have power and how they can influence society.

Knowing how little freedom of expression there is in the Polish media, why do they work as journalists in this country?

Le Clerq sighs and smiles at me.

“It all depends on what city you are in and what the local ideology is. For example, the city of Gdansk is very progressive and rich. Economically it is strong and that is reflected. It is an open city, people participate in voting. This encourages the media to take their work more seriously and to put themselves in the public eye. The error when writing becomes more serious.”

Anna settles at her desk. She shows me some of her articles and smiles. She takes a sip of coffee.

“Personally I haven’t come to experience that “Media Control Act” in any case. I appreciate that. However, I do know of cases of colleagues who may have been caught between a rock and a hard place at times for wanting to tell a story one way or another here in Poland.”

But what exactly does this Media Control Act consist of?

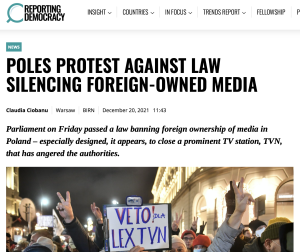

Anna shows me a news item from the newspaper “Reporting Democracy”. I start reading. I drink from my cup and there is silence in the room. Now I understand exactly what she is talking about.

Poland’s lower house passed its controversial media law in 2021. This new regulation prevented companies from outside the European Economic Area from participating in the control of Polish media companies. According to critics, it was intended to silence independent news channels. According to EuroNews, the law would prevent any non-European entity from owning more than a 49% stake in television or radio stations in Poland.

How does this situation affect the profession of journalists? I fail to understand how a journalist can feel good working under such conditions.

Again Anna drinks her coffee. I stare at her home office. On the table are two computers, newspapers scattered on the table and a notebook. I stare at her and there is silence. Now you no longer work for Reuters,” I say, “now you are free to write absolutely anything you want.

“Indeed, after working for Reuters for 7 years I decided to start working independently and not exclusively for one media. I wanted to experiment and be my own boss, what is known as a “freelancer”.

And what kind of news do you cover and what is your day-to-day life as a freelancer like?

“I work 80% as a freelancer at home, which is called “home office” with interviews usually done through ZOOM and then 20% of the research and interviews are done outside the home.

Anna points to the door. She wants us to go outside to see how that 20% works. She picks up her notebook and asks me to accompany her down the stairs. We walk around Gdansk. He shows me the Motlava River, now frozen with cold.

“I cover all kinds of news: economic, social and human rights here in Poland. I want to tell interesting long stories that help make minorities visible. I divide my work into two sections. On the one hand, I write short news stories. I talk about what is happening in Poland, I deal with news that is relevant to the public. On the other hand, I write features, long reports. These take me days of research because they tend to be topics that interest me more, for example “inflation in Poland”.

And what about the rest of Polish society, does it agree with this situation?

Certainly not. In 2021, when the Media Control Act came into being, Polish citizens took to the streets in protest. As many as 126 cities in the country appeared at the call with banners against the so-called “Lex TVN”, as it is called and would become a “propaganda” media of the national-conservative ruling party Law and Justice (PiS).

Among those opposed to the law was US Department of State spokesman Ned Price. According to Reporting Democracy he declared: “The United States is deeply concerned about the passage of a law in Poland today that would undermine free speech, weaken media freedom, and erode foreign investors’ confidence in their property rights and the sanctity of contracts in Poland”. But this is not new, it has been around for a long time. The passage of “Lex TVN” is part of an ongoing assault on media freedom in Poland since PiS came to power in 2015. The approval of “Lex TVN” is part of an ongoing assault on media freedom in Poland since PiS came to power in 2015.

In the Polish media there are big differences between the state media, where there is more control over the way news is presented, and the independent media of recent years. When it comes to talking about the LGBT community, the government would probably never interview you, but if you come from another newspaper that praises the city, you have no problem there. A few years ago, the “verbal aggression” towards the LGBT community was very strong from the government. The situation has improved somewhat. The issues to focus on have changed, from LGBT in 2015 to refugees and now to Ukraine” Le Clerq says.

Working independently and moving away from impositions is not an easy task. Currently the situation of “censorship” is more delicate than ever as the ruling party first established political control over public media and then redirected public advertising from independent media to the channels it controls. And of course, this situation has led to more than 50 Polish media outlets continuously protesting against a new tax that stifles their independence because the media live mostly from advertising. Thus the government’s aim is to liquidate free public opinion, which results in an imprisoned society. This tug-of-war creates more and more tension among the population and a feeling of mistrust between the state and the population.

Will it be necessary to become a freelancer to work in full freedom in Poland? Le Clerq and Rzhevkina are clear. The future of media freedom is now in the hands of journalists and, of course, of the Polish people, who no doubt declare themselves to be lovers of freedom of expression.

Mercedes Vilaclara