The Hungarian economy has been struggling for some time, and a new peak has been reached as the average inflation has risen above 25%. The government blames the war in Ukraine and the sanctions imposed by the EU on Russia as the cause. However, even within the government, there are serious doubts about this explanation. The sanctions seem to have little impact on the Hungarian economy. Economic unrest in Hungary is caused by factors such as excessive spending from the state budget, particularly before elections, says Hungarian journalist Sándor Joób. Hungary needs the billions of EU-funds to keep daily life affordable.

On a cold December morning, Judit Almàsa steps out of her apartment in Budapest at around 5am. Her building is located in Hegyvidék, the 12th district of Budapest, a hilly and wealthy neighborhood filled with large residences, villas, and monumental buildings. Her destination is the Tesco supermarket around the corner. “We call it the peasant shop actually,” she jokes on the way. “They really rip you off here. Because they know the people who come here can afford it anyway.” Judit herself does not live in one of the large villas, but in a small 50m2 apartment with her daughter. Outside the supermarket, there is a group of five men in thick winter coats holding cups of Glühwein. One of them is selling a stack of Christmas trees next to the parked cars. Inside, the heater is running at full blast. Judit unzips her coat with her left hand and grabs a basket from the stack with her right. At the pasta section, she points to the white card on the shelf. A package of pasta costs 1319 Forint, equivalent to about €3.20. A package of cheese costs 1079 Forint, and a box of eggs at least 1350 Forint. “It’s fucking crazy, how could anybody afford to buy this crap,” Judit mutters. Prices of products significantly increasing is something that people in Hungary are used to. The value of the Forint has been fluctuating for years.

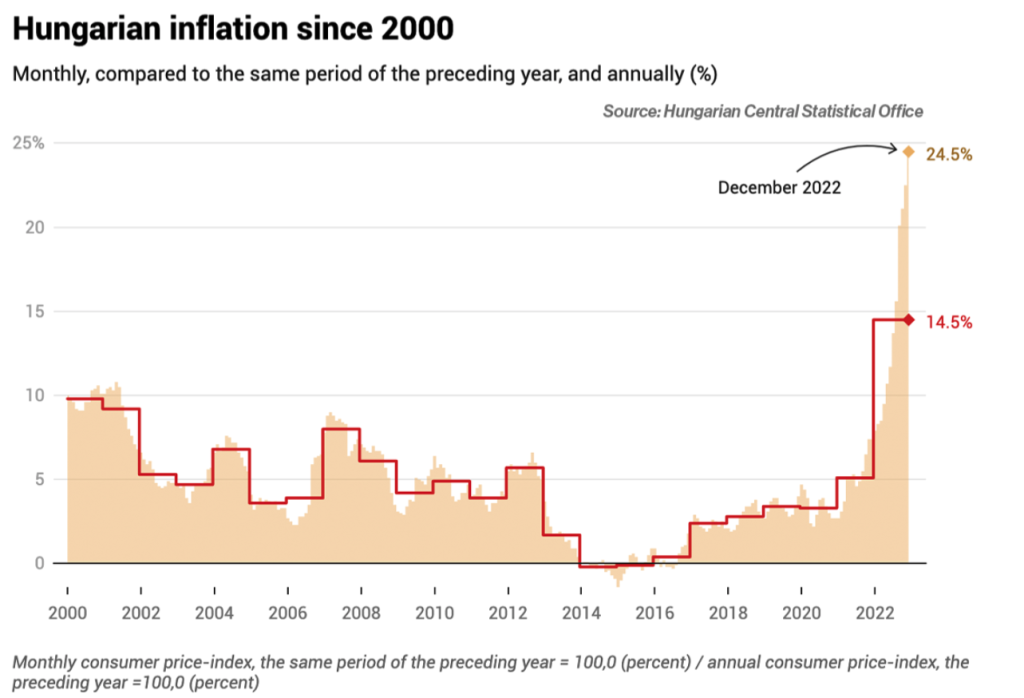

This is one of the reasons why the country is still not a candidate for joining the Eurozone. But the price increases of the past year have been terrible. The average inflation in Hungary reached a record high of 24.5% in December compared to the same month a year ago. But the average rise of food, for example, is more than 40%. “It’s gas prices, groceries, pet food, alcohol; I was unable to get any gasoline for a while actually.”

As she walks back home with her groceries, Judit is irritated by the high prices. She understands that inflation is a major problem in Hungary, but she still feels cheated by the increasing costs of the products she needs on a daily basis. “I can still afford it, I am lucky with a good job. But people in the countryside, they make no money. They can’t afford 1300 Forint for eggs. Fucking eggs!”

Hungary is not the only country in the EU facing rising inflation. For most countries, shortages in the energy market, partly due to the war, and the aftermath of the COVID pandemic are the major factors. The European Central Bank decided to raise interest rates to 2% to counter the devaluation of the euro. The average inflation of the entire European Union was 9.20% at the end of 2022. Hungary’s inflation is therefore significantly higher than surrounding countries, despite various measures to curb it.

First, the Hungarian central bank (Magyar Nemzeti Bank) decided to raise interest rates by more than 18 percentage points from June 2021. During a parliamentary hearing on Monday, December 5, György Matolcsy, head of the central bank, criticized the government’s economic policy. He said: “We have to face the fact that our finances are among the worst or second worst in the European Union. Next year […] we have to face that if Hungary does not change its economic policy, it will lose this decade, and stagnation, stagflation will follow. This can still be reversed, but it will be too late next year.” To counter panic among citizens about price increases, the government imposed a price ceiling on various basic products. For thirteen months, Hungarians were able to buy gas for 1.16 euros per liter. However, this had the opposite effect. Fuel exporters stayed away from Hungary because there was not enough profit to be made due to the price ceiling. Empty pumps and long lines followed, so the government had to force the release of the price ceiling.

Journalist Sándor Jaób from TELEX

“Even more important for the deterioration of the situation was the exorbitant amounts that the government distributed just before the elections,” says Sándor Jaób, journalist of the independent Hungarian news platform Telex. “The irresponsible and sanctimonious payouts created a 1,500 billion HUF gap in the government’s budget. Of course, the distribution of money has resulted in increased prices due to the rise in demand.” The inflation is now pushing people with low incomes below the poverty line in the country and making basic needs unaffordable. “We think this is one of the reasons shoplifting has increased more than 22% compared to last year. Mainly theft of food items such as pasta and dairy.”

Inflation is not a new problem for Hungary. The country has already experienced the most severe inflation ever seen, namely after World War II. The former currency, the Pengo, dropped to a bizarre value in just 2 years.

Hungarian Pengo

For a long time, the Pengo was considered one of the most stable currencies in Eastern Europe. The Hungarian government had a hard time paying for the costs of the war. Large amounts of money were printed, causing a crash in the value and trust in the currency. Inflation reached a record high of 41,900,000%. This had a major impact on the Hungarian economy and the standard of living of the population, who saw their savings and income become almost worthless. The huge fluctuations in value led to total chaos, which only intensified inflation. At the peak of inflation, prices doubled every 15 hours. The Pengo was eventually replaced by the current Forint in 1946. 1 Forint was equal to 400,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 P (4×1029 Pengo). That is a 4 with 30 zeros.