Berlin’s techno culture, often referred to as the ‘capital of techno’, began as an underground movement after the fall of the Wall and has since grown into a symbol of inclusivity. But as the city changes, the scene is under pressure — reshaping the identities of iconic clubs and their audiences. Inclusivity may be its greatest strength, but also its most complicated challenge.

From outside the bar Lauchangriff, in the area of Friedrichshain in Berlin, a hard and fast tempo sound is heard. Organizer Apolline Chasseloup is testing out the sound system before her donation-based event starts. Where UK garage meets heavy, hard industrial and hardcore industrial music, and the people can pay what they can and want once they go in. The event being donation-based was not necessarily by choice. “I could have said that it’s a free event, but I want to be able to give something back to the DJ”.

Also speaking as a DJ herself, known as HNO3: “If the crowd get used to free events, it will break the standards of the markets. We’re not paid a lot right now, and we will get even less paid.” The different struggles as an organizer, DJ and as a party-goer in the scene are crossing over.

The legacy of Berlin’s techno scene’s liberation

Berlin’s nightlife has deep cultural roots. Since the 1920s, it’s been a space for diversity and expression, particularly for the LGBTQ+ community. After the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, abandoned spaces in the East became fertile ground for electronic music and new forms of freedom. “The history of how the Berlin club scene came to be is super important to understand what is happening now,” says Gregor Kusche, who’s been running the club Klunkerkranich for 12 years.

DJ Westfa, also known as Jozua Tuinfort, adds: “Nowadays, the acknowledgment for artistry within this dance culture is lacking. People now go out through TikTok to see their favourite artist, not realizing dance culture comes from oppression.” He highlights how the scene has grown more image-driven: “You need to have a certain appealing appearance, a certain stage presence. It has become much more difficult for an introverted artist to be recognized.”

Economic shifts and loss of access

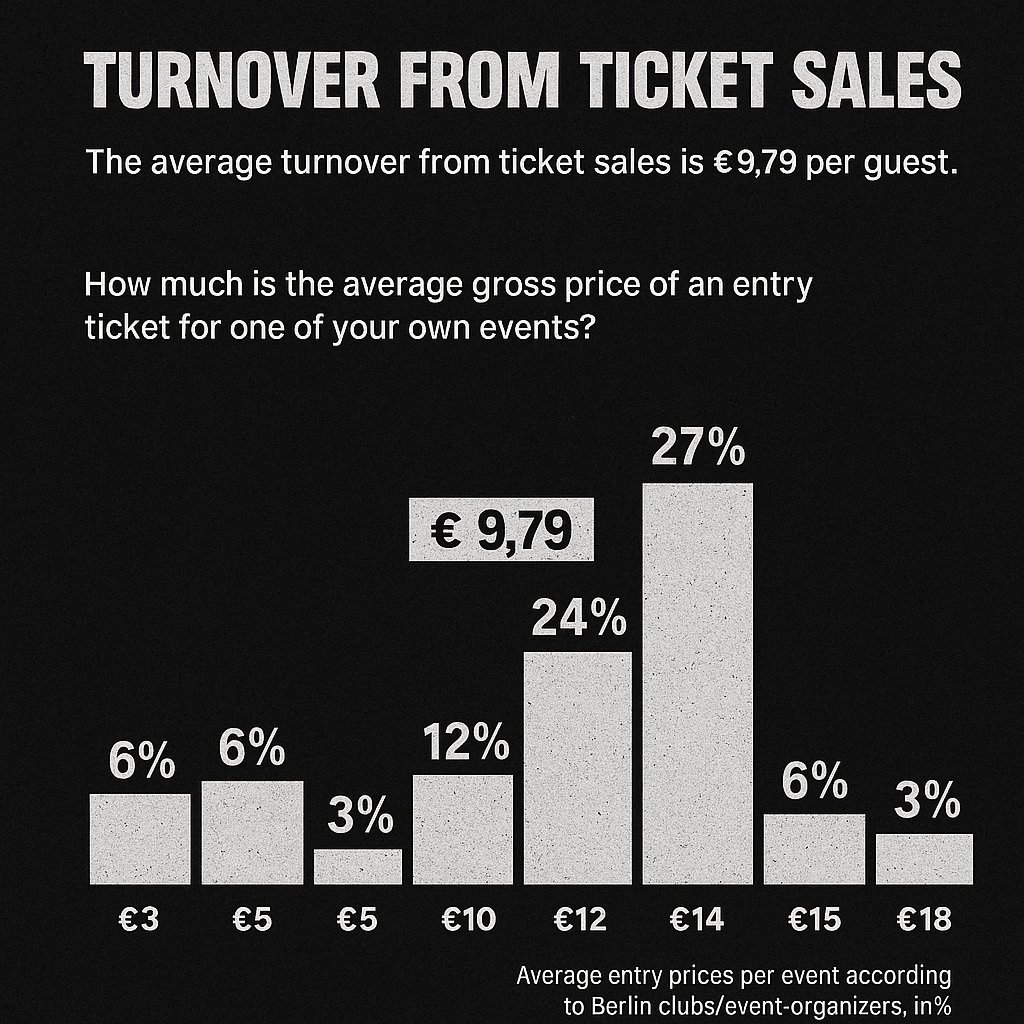

Berlin’s club scene, once grassroots and rebellious, has become a major economic engine. As Kusche puts it, “Berlin won’t get cheap overnight again. That ship has sailed.” According to a 2019 Clubcommission Berlin study, the scene generates €168 million annually and supports sectors like hospitality and music. Despite this, clubs get no state support and depend entirely on private income.

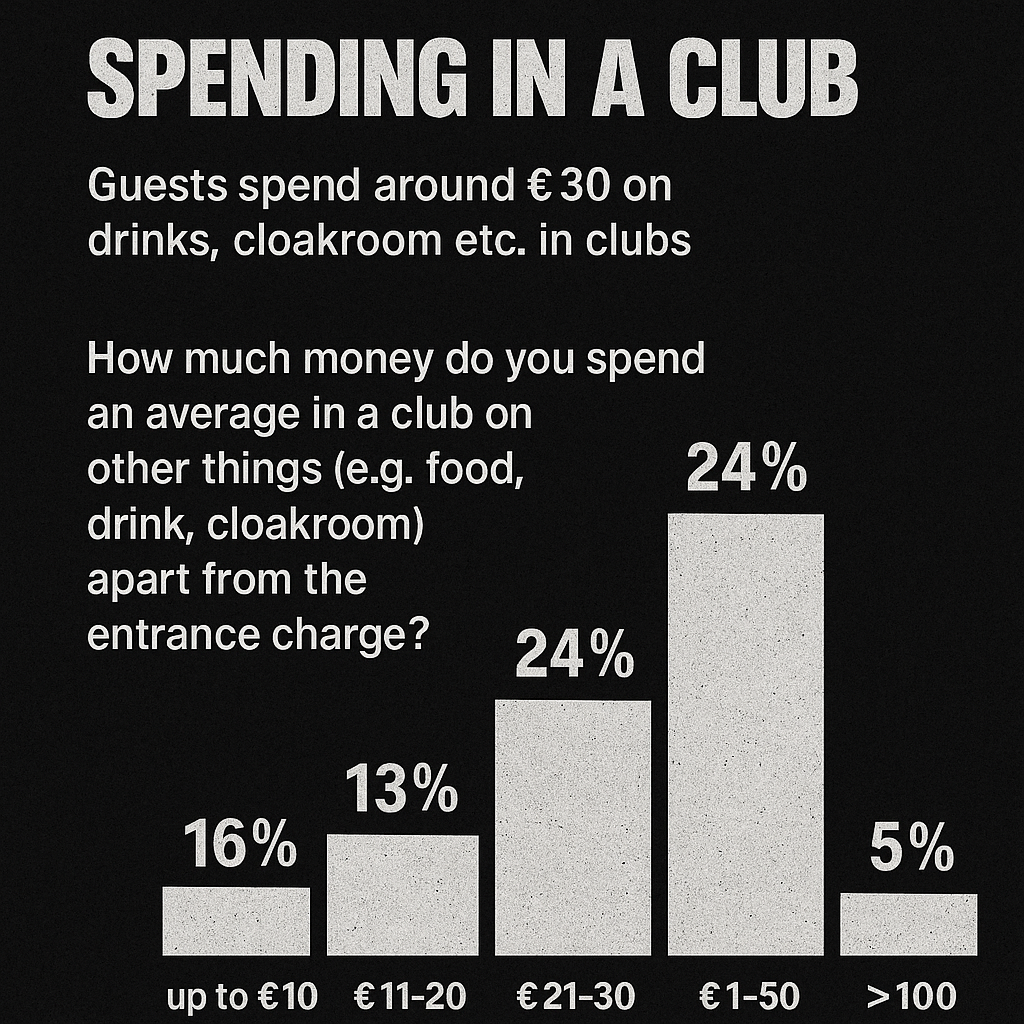

Gentrification and rising rents are forcing clubs out of central areas. Ticket prices and drinks have risen, making nightlife less accessible—especially for marginalized groups. “It became much more exclusive,” says Tuinfort. “At Berghain, you just see that the people do have income. It becomes much more inaccessible, especially for younger people exploring club culture.”

The same Clubcommission study found that 55% of clubs saw declining sales, and nearly two-thirds saw profits fall—smaller venues were hit hardest. Almost half were considering closing within the year, and 89% reported major cost increases in rent and energy.

This study was carried out on behalf of Berlin’s Senate Department for Economics, Energy and Public Enterprises. Published by Clubcommission Berlin in 2019. Clubcommission Berlin is an association and union of organisers of Berlin clubs, parties and cultural events, registered since 2001. As a mouthpiece for the Berlin club scene, they want to ensure that the concerns of the club scene in Berlin are taken into account in politics and business.

“The whole alternative scene has always been about doing new things.”

‘Clubsterben’

Higher prices and outdated programming are making Berlin’s club scene less attractive to younger audiences. Consequently, admission prices have surged, with smaller clubs charging around €15 and larger ones up to €30. This makes club hopping unaffordable for many, contributing to a decline in audience numbers. The phenomenon of clubsterben—or club death—is a spoken about thing, underscoring the city’s cultural image and the economic realities threatening its core values of openness and inclusivity.

With iconic venues like Watergate closing in 2024 and Wilde Renate set to close at the end of 2025 because of high rents, war, inflation, and rising costs. Declining accessibility as rising costs reshape who can participate in the city’s once-inclusive nightlife. But this trend narrows programming and excludes emerging talent. “If you just give money to everybody to make everything the same forever and ever, then it can’t be the solution to everything,” says Kusche. “The whole alternative scene has always been about doing new things.”

Watergate’s sign remains as a silent marker of its cultural legacy, even after its closure in 2024. And the closure of Wilde Renate at the end of 2025 marks another loss in Berlin’s underground nightlife.

Finding solutions

While there are challenges, the scene is also coming up with new ideas, solutions, and counter movements. Kusche acknowledges the hard truth for many clubs today: “Either you really reinvent yourself or you think outside the box, or you have to close sooner or later.” A good example is from Tresor.West founder Dimitri Hegemann, when he revealed Community Nights last January, with their #SaveTheUnderground campaign.

Hegemann, with more than three decades of experience running the world-famous Tresor club in Berlin, is now finding success with an alternative strategy at the struggling sister venue in western Germany. The events see the venue offer free entry with an unannounced line-up, attracting more footfall by making nights out more affordable for young clubbers, as well as giving a platform to the next generation of DJs. Calling Tresor West a “huge movement,” Tuinfort praises their approach: “They’re giving back to the community, making it more accessible.”

Other examples of new ideas and salutations are donation-based, sliding scale entity, charity-based, and community tickets. Jozua Tuinfort thinks this also makes a huge difference in the crowd who comes to those events: “You have a much more open, relaxed type of crowd in a certain way. Many more people come from different backgrounds, who actually come with a sort of motivation to support a certain cause or collective.” But “Let’s focus less on the outside,” Tuinfort concludes. “More on what you can accomplish with the people around you.”

Voices from Berlin’s club scene

Berlin’s club culture has different groups within its community and is created by the organizers, the DJs, and the audience. Within this community and groups lies tension between exclusivity and inclusivity, shifting and constantly negotiated. The different voices from the scene show the changes and tension that are the current club culture.

Jozua Tuinfort / DJ Westfa

Apolline Chasseloup / HNO3

Gregor Kusche – Club Klunkerkranich

Sami Akouz – Visitor donation based party