Vienna celebrates itself as a capital of culture. With a variety of museums, theatres, and concert halls, and with policies like “Culture for All,” the city projects an image of inclusion. But how inclusive is Vienna’s cultural life for people with refugee backgrounds?

On a sunny evening on June 29th in Vienna’s 16th district, the doors of Brunnenpassage open for a new event. The entrance to Brunnenpassage doesn’t hide what it stands for. Multilingual words – “Inspiration,” “Doživljavanje,” “Muzika,” “Sinema” – are printed across its glass façade. Inside, today the stage belongs to Serbian comic artist Aleksandar Zograf, who speaks about war, migration, and memory through illustrated panels. A boy draws in the corner. A woman whispers translations to her husband. At first glance, it’s just another cultural event. But in a city that claims “Culture for All” as a policy goal, such scenes remain the exception.

Austria’s Integration Act of 2017 outlines the core elements of refugee integration as language acquisition, employment, and civic orientation. Culture is not mentioned and reinforces the view that cultural access is optional, when in fact it plays a major role in belonging and identity in a multicultural society. For many refugees, the question is not only whether they can stay in Austria, but whether they can belong and gain access.

- Some of the volunteers at the Brunnenpassage event.

- The audience looks intently at the stage.

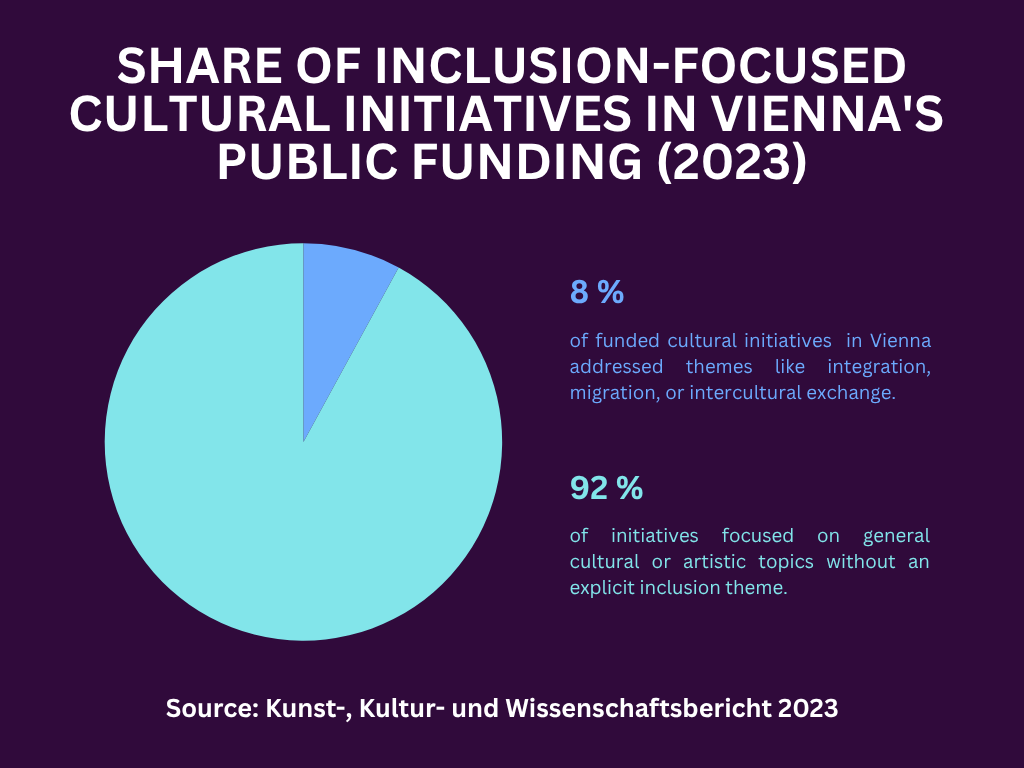

Vienna’s population is nearly 50% migration-background. Despite this, cultural institutions remain dominated by native-born Austrians and long-established audiences. According to the “Art, Culture and Science Report” by the City of Vienna in 2023, only 14 of 176 publicly supported cultural initiatives explicitly focused on migration and integration. Culture as part of refugee inclusion remains underprioritised. Based on the Integration & Diversity Monitor in 2023, one in four migrants in Vienna reports experiencing discrimination – often subtle, sometimes structural. Cultural spaces reflect these dynamics. In the same study, many respondents said they avoid certain venues because they fear not being welcome or worry about language barriers.

Access to cultural events is also a question of money. The 2023 SORA study (pdf) on cultural participation found that only 18% of people attend cultural events regularly, and participation drops sharply among people with lower income and education levels. That’s what makes low-barrier initiatives like the Kulturpass so significant. Since 2003, it has allowed people living below the poverty line – including many refugees – free access to theaters, concerts, museums and more. Over 65,000 people now use the pass nationwide. “It opens a door,” says Monika Wagner of ‘Hunger auf Kunst und Kultur.’ “But what happens once you’re inside – that’s up to the person, and to the space.”

While the Kulturpass offers access, it does not necessairly offer support. That’s where the Kulturbuddy Project comes in. Organised by Caritas Vienna, it pairs for example refugees and socially isolated people with volunteer companions who join them on cultural outings. In 2024, 93 volunteers accompanied 822 participants. “It’s not just about going to a concert,” says coordinator Iris Brinkmann. “It’s about going together and feeling like you can be there.”Brinkmann has also observed differences between communities: “Ukrainians often use cultural offers very practically as distraction or routine. Afghan and Syrian refugees are more focused on building relationships and continuity.” Return visits are key. “Some people come once and never return. Others come back and bring friends. That’s when you know trust is there.”

The approach taken by Brunnenpassage, a cultural space housed in a former market hall in Vienna’s Ottakring district, is cultural inclusion and participation. It hosts over 400 events per year, many of them co-designed by people with refugee or migration backgrounds. “We don’t make projects for refugees,” says co-director Anne Wiederhold-Daryanavard. “We create them with them. And that changes everything.”

Brunnenpassage also integrates former participants into its volunteer and production teams. “Some of the people who first came here through a buddy or a family program are now part of the team. They didn’t just stay, they helped shape what this place became,” Wiederhold explains. The difference is visible. Children aren’t told to sit still. Multilingual moderation makes space for different comfort levels. The room feels like a place to stay and not just pass through. “People come, and they come back,” Wiederhold adds. “That’s often how we sense that trust has been built.”

- Events at Brunnenpassage rely on volunteers.

- The spectators at the event are very diverse.

- Translations in various languages at the door.

According to Azadeh Sharifi, who studies refugee artists in Austria, cultural institutions often invite participation without shifting power. “Refugee artists are invited,” she writes in the Journal of Refugee Studies, “but often as guests, not co-creators. Symbolic inclusion is common. Structural inclusion is rare.”

Brunnenpassage remains one of the few venues in Vienna where co-authorship is practiced at scale. But such models are fragile. Projects like Kulturbuddy rely on volunteers. Brunnenpassage operates with a patchwork of city, federal, and philanthropic support. Measurement remains another challenge. Although these models can collect figures and data on tickets and visitors, it is hardly possible to measure the extent to which integration and participation for people with a refugee background is actually achieved in society.

For Wiederhold, the future of cultural inclusion depends on presence and persistence. “We should just be there more,” she said. “They should feel safe and accepted. It’s not always about the show, sometimes it’s about the space.”