In the Corona pandemic, the Roma, Europe’s largest ethnic minority, are a particularly vulnerable group due to economic deprivation and poor living conditions in slums. However, as the right-wing populist government in Bulgaria refuses to provide adequate support, their situation will worsen in the future, NGOs say.

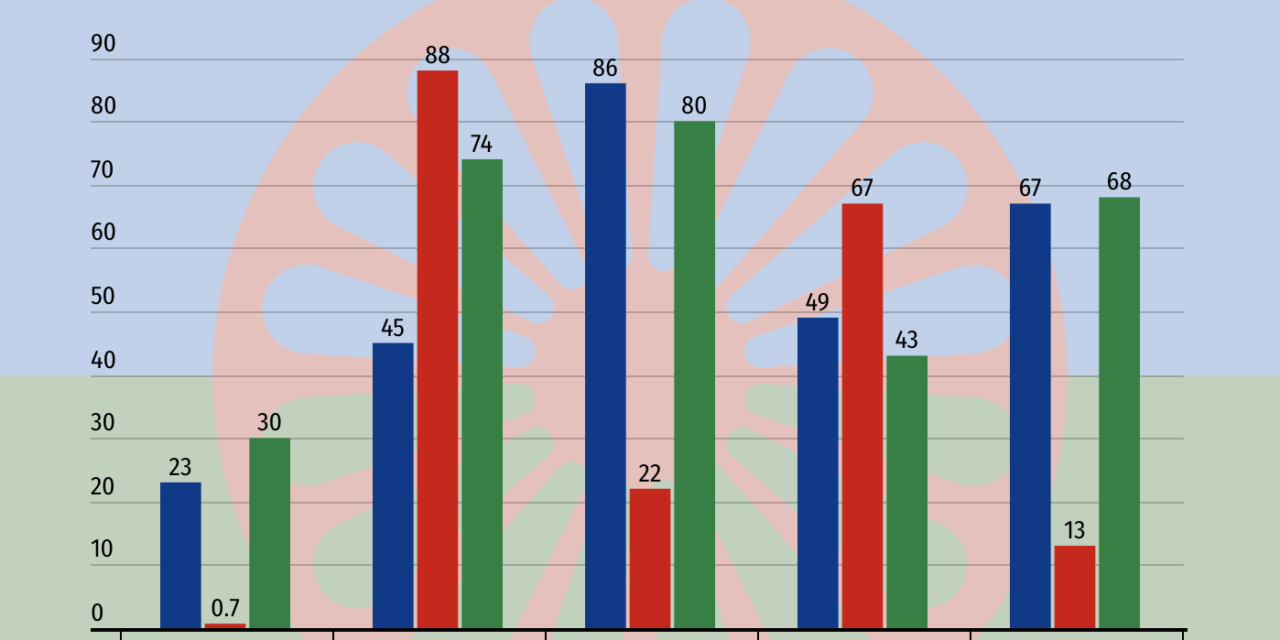

Washing hands and keeping your distance – the supposedly simplest protective measures in the fight against Covid-19, which after a year have become part of everyday life for a large part of the population, still pose a challenge for many of the 750,000 Roma in Bulgaria. According to the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 23% live in houses without water supply and have to walk between one and two kilometres to reach clean water. Mostly concentrated in isolated and overpopulated neighbourhoods outside the regulated urban fringes, Roma have an average living space of 10.6 m2.

But instead of offering help to Europe’s largest ethnic minority at the beginning of the pandemic in March, Bulgarian officials were quick to use them as scapegoats. After members of the national government had referred to Roma neighbourhoods as “the real nests of contagion” from which the rest of the population needed to be protected, local authorities erected temporary walls in at least six areas and set up police checkpoints that prevented residents from leaving unless they had a job or a medical emergency. In Burgas, drones with heat sensors were used to identify people with higher temperatures and in Yambo an airplane sprayed 3000 litres of disinfectant on Roma houses and neighbourhood streets.

This was done without any indication of higher infection rates and quickly proved counterproductive, says Bernard Rorke, Advocacy and Policy Manager of the European Roma Right Centre (ERRC): “If you blockade neighbourhoods and you deny people access to clean water and sanitation what you are doing is aggravating a situation and making it worse.”

Political weaponization of anti-Roma racism

Generally speaking, antigypsyism has a long history. The 12 million Roma in Europe, who originate from northern India, have been subjected to constant exclusion and demonisation since they first settled on the continent around 1,000 years ago. Following an ERRC report co-authored by Rorke, Bulgaria was not the only country where the Roma community faced discriminatory measures during the first wave, which “goes back to age old prejudices of minorities being the bearers of viruses,” he explains.

What makes the Roma in Bulgaria exceptional is the state of the political elite, Rorke notes: “There is a more explicit political weaponization of anti-Roma racism for electoral gain. In times of uncertainty, when ethnic majority seeks out scapegoats, there are political entrepreneurs on the far-right who will exploit these tensions.” Nikolay Kirilov, member of the Roma Standing Conference agrees: “The current political situation is key to understanding the current and the future policy responses to Covid-19.”

Since the openly fascist “United Patriots” alliance became a coalition partner of Prime Minister Boyko Borisov’s centrist GERB party in 2017, the ERRC has repeatedly complained to the European Union about increasing hate speech by people in high office, house demolitions as a form of collective punishment and open incitement to racist violence by leading members of the government. The only Bulgarian politician ever to be charged in connection with hate speech was former Deputy Prime Minister Valeri Simeonov, who shortly afterwards was appointed head of a national council responsible for the integration of the Roma population.

In the run-up to the 2019 European Parliament elections, the defence minister and leader of the nationalist VMRO party Krasimir Karakachanov proposed a “concept for the integration of the unsocialised Gypsy (Roma) ethnicity”, which was highly problematic from a human rights perspective. On the other hand, less than 3% of the funds earmarked for Roma inclusion measures between 2014 and 2018 ended up with the community, a study by the Institute for Public Environment found.

Bulgarian society widely supports the anti-Roma agenda, one reason being that 90% of the media is in the hands of the ruling parties, which use it as a mouthpiece for propaganda. Moreover, Roma lack political representation, Kirilov states: “There is not a single Roma in a managing position in Bulgarian government, not in the local, not in the regional, not in the national. The Roma are totally excluded from any position on the decision-making level.”

Long-term impact less health-related than social

During the second wave, monitors on the ground did not see any of the incidents they saw in the spring, says Rorke. This does not mean that things have become easier. Even though society was much more informed, the Bulgarian government failed to prepare, and stricter measures were announced too late, Kirilov adds. Another big problem are the huge channels for disinformation around Corona, especially in the Roma communities. “Now we can see that 70-80% of the Roma communities are affected and there is a very high percentage of mortality.” Less than 50% of the minority group are covered by health insurance.

In Kirilov’s eyes, however, the long-term impact of the pandemic on Roma in Bulgaria will be less health-related than social, political and economic. “The main beneficiaries of the job-preservation policy are relatively large firms. None of these policies apply to self-employed or to inactive, not formally employed, discouraged job seekers and all other persons outside the labour market but in active age.”

Many of the 1.2 million people therefore excluded are of Roma origin. Even before the outbreak of the virus around 55% were unemployed, which can only partly be explained by low education and skill levels. Due to widespread negative stereotypes, Roma are severely discriminated against in the labour market. Many of those who rely on irregular employment such as street vending and collecting discarded materials are unable to go out and generate income as a result of the crisis. While 86% had already been at risk of poverty, the ERRC found that the median income in Roma neighbourhoods fell by a further 60%.

According to Kirilov, the Roma are a little better off at the moment, coming out of the summer where they were able to work temporary jobs and save up a little income, but the most difficult months are still ahead: “Most of the Roma communities rely on the income of the diaspora because of the people who are economic migrants in the West. They send money to their families, but we know that most of them will lose their job.”

No faith in the corrupt government

In the meantime, school children are struggling with digital learning. “If you live in an overcrowded dwelling sometimes without electricity, without clean water, sanitation, without Wi-fi, then there aren’t the devices,” Rorke explains. “We have found that kids have lost a number of months in their schooling and it is going to be a big question how that is going to be made up again.” Kirilov says, the Bulgarian government announced a plan to buy 100,000 devices, but so far only 7,000 have been distributed. Even before the pandemic, 67% of Roma children, often enrolled in racially segregated schools, left education early, resulting in a significantly higher illiteracy rate compared to ethnic Bulgarians.

“Under more favourable circumstances the gap was already widening. With the complete dislocation that has occurred, it will definitely get far worse and the full impact will only be felt in time,” Rorke predicts, adding that the grey market is also dependent on a thriving economy in general. “I have no faith in the capacity of the government to repair the economy, get people back to work and pay any attention to the needs of those who are living in the most precarious situations.” Since July people have repeatedly taken to the streets to protest against their corrupt government.

Kirilov agrees: “If you read the strategy for the next programming period and if you follow the post-Covid crisis plan of the Bulgarian government, in a hundred pages you will find the name Roma in the document only once.” He fears that in view of the lack of prospects for the minority in the next generation, migration to the West will increase even further.

A scar on Europe’s conscience

Calling the lack of support for Roma a “scar on Europe’s conscience”, in October the European Commission put forward a new ten-year framework for the inclusion and participation of Roma, very much appreciated by Rorke: “I welcome the Commission’s moves to raise the profile and awareness around anti-Roma racism, for citizens of Europe to recognize that this is a historically rooted, long-established form of racism that destroys opportunity, insults the dignity, autonomy, safety and security of our fellow citizens every day.”

However, he is afraid that the second framework will have limited impact for the same reasons as the first one – member states failing to implement policies and act in good faith. “If the targets for 2030 are to be met, there needs to be a greater focus on constraining police brutality, issues like forced evictions and school segregation. All these issues need to be as forcibly addressed as possible by the Commission but ultimately the responsibility is with national governments.”

In Rorke’s eyes Roma inclusion needs to be part of a wider fightback against the politics of the nativists in Europe, including the condemnation of hate speech by those who hold public office as well as closer scrutiny of the use of EU funds. How this will play out in the next decade remains to be seen. “The reality could be that people will just muddle through this crisis and get back to being as bad as ever.”