The ten most expensive paintings in history were all painted by men. Even in the 21st century, women artists continue to be underrepresented in galleries, museums and at auctions – here’s why.

“As we all know, things as they are and as they have been, in the arts as in a hundred other areas, are stultifying, oppressive, and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class and, above all, male.” These lines were written by art historian Linda Nochlin in 1971 in her essay “Why have there been no great women artists?”, yet they seem to be just as relevant 50 years later. To this day, only two works by women have made it into the top 100 auction sales of paintings, although about half of the top 25 have women as their subject.

“In historical times, there was quite simply a lack of training opportunities, of options to gain visibility and thus also to gain a reputation,” says Katrin Hassler, art sociologist at the University of Lüneburg. Up until the 19th century, women were barred from studying the nude model and certain prestigious institutions such as London’s Royal Academy of Art didn’t allow women to study at all.

Those who managed to assert themselves have mostly disappeared from the collective memory, but art historians are trying to help them regain visibility. One of them is Camille Morineau: “At the time the critics were macho, they could only write about men, but if you look at the list of artists in the exhibitions, you’ll find quite a lot of women artists in those shows.”

In 2009, she experienced first-hand how scarce information about female artists is when she curated the exhibition elles@centrepompidou with exclusively female art – at that time a novelty. She then decided to found AWARE, a non-profit organisation that publishes free content about the work of 20th century women artists on its website. By doing so, Morineau wants to break a vicious circle: “When you realise that there are a lot more interesting artists than you think, you want to buy them, you want to show them, you want to write about them and by producing this information, exhibitions or books, you create value for the artist.”

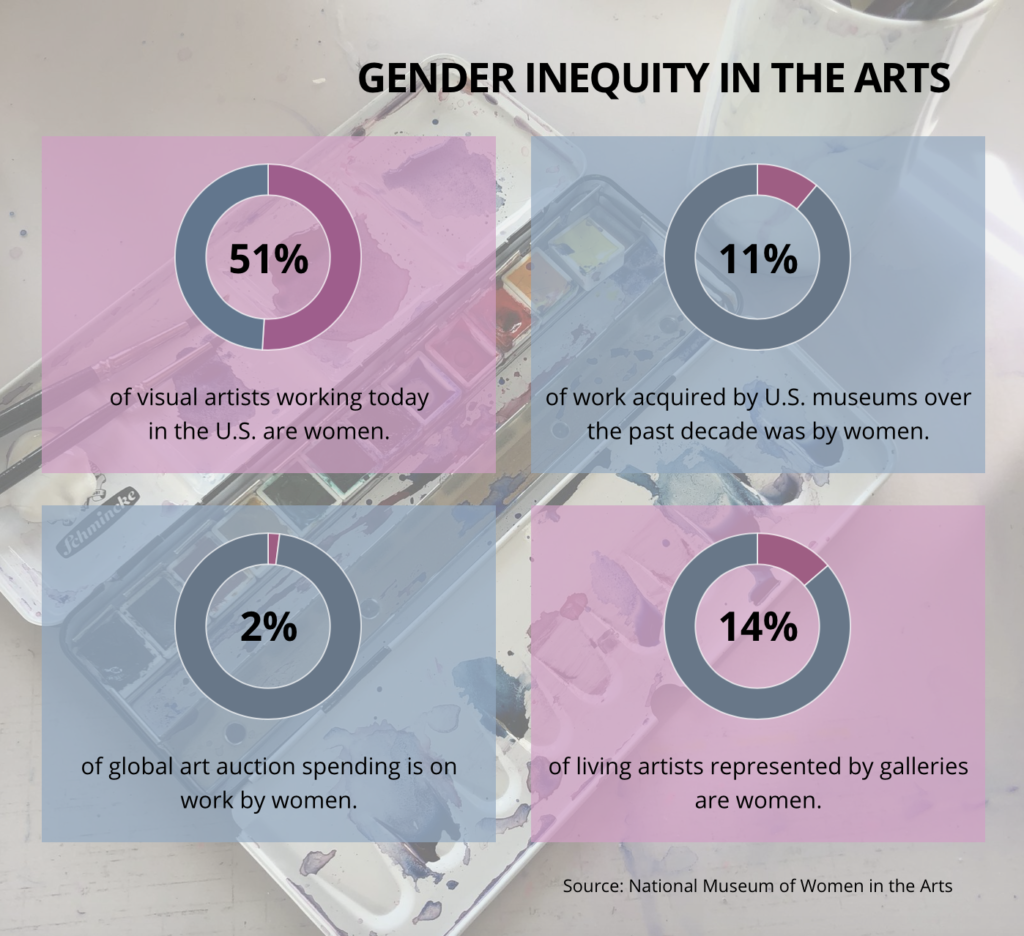

Of the $196.6 billion spent on art at auction between 2008 and 2019, work by women accounted for just 2%. A study from 2017 shows that viewers rank images higher if they are attributed to a male artist – one reason being that there is a lack of role models, Hassler explains: “If I proceed purely rationally on the market, then of course, in a risk assessment, the safe way is to bet on the men, where you know they achieve their prices.”

The lack of role models also affects the next generation of women artists. Although more than half of art school graduates today are women, only 1 in 10 living artists represented by galleries are female. “If there were more women artists in official art history, then maybe more art students would feel better about themselves and decide to become great artists,” Morineau suggests. Gender-based education still plays a role as well: “Women haven’t been told how to promote themselves and it’s an important thing as an artist to be able to talk about your work, to feel that you’re strong enough to meet a gallery and say, listen, I’m a really good artist.”

“This is an exclusion that works very subliminally and is hardly visible, which is why it’s so difficult to grasp and is often not even identified as such,” says Hassler. In addition to male professors at art colleges, who tend to promote male students more strongly, and poor compatibility with family life due to financial risks, the sociologist cites a reason already mentioned by Linda Nochlin: “In the art field, we’re still confronted with the myth of the artistic genius, which historically has strong male connotations.”

Nevertheless, things have improved since 1971, which Morineau partly credits to #MeToo. “Some galleries now specialise in discovering artists from the past. They really make a living out of these historical women artists,” she notes. Studies suggest that female artists are the best investment because the prices of their works are rising much faster than those of men. Another trend that can be observed is that of all-female exhibitions. A 2018 exhibition of work by the artist Hilma af Klint ended up being the most-attended museum show in the Guggenheim’s history.

Some are critical of this development because they fear that it will once again ascribe a special role to women artists, but Morineau is positive about it, using the upcoming exhibition “Elles font l’abstraction” at Centre Pompidou as an example: “The artists have nothing really in common other than being abstract and being women. For many years, most of the shows were done with only male artists.”

Nevertheless, the issue must continue to be raised, “to show that we are not at the point where people often think we are,” Hassler warns. Here she would like to see a stronger focus on intersectionality. Likewise, Morineau wants to create more awareness for black and queer artists through AWARE. Both the sociologist and the curator see the responsibility for driving change primarily at art colleges and universities, where the next generation of artists and art historians are trained. However, each and every one of us must also do their part, Morineau believes: “The chain of recognition is something that is collective work. When you decide to visit the show of a woman artist and pay for a ticket, or as a collector you decide to buy a woman artist, you contribute to this change.”