A young woman in a white dress is running through a forest in Transylvania. Horror marks her face, tears are streaming down her face, scratches and wounds cover her body. Dramatic music accompanies her flight from a dark evil that is all too familiar to the audience in front of the screen: Count Dracula. The music is getting louder, the tension builds, and then there he is – the world’s most famous vampire caught up to his victim. The screen goes black, the end credits roll. And a cinema full of people silently agrees: Transylvania is not a place they ever want to visit.

When thinking of Transylvania, the association with vampires comes almost naturally. This image has been shaped by decades of films and novels across genres, from romance to horror to young adult novels. It often seems like a fantasy world, similar to Wonderland or Gotham City. But in truth, Transylvania is a real region in a real country, home to real people – and a lot of folklore.

Most of that folklore originates from one man: Vlad the III of Wallachia, or as he was also called, Vlad the Impaler. His nickname during his lifetime: “Dracula” – son of dragons. And then there was a second man, many years later, a writer called Bram Stoker.

“There’s no evidence that Bram Stoker knew anything about Vlad III of Wallachia. He simply knew his nickname of Dracula, which to him sounded like a great name for a monster.”, explains Duncan Light, a tourism academic at Bournemouth University, who has studied Dracula tourism in Romania for over two decades. And just like that, Count Dracula was born in 1897 – half myth, half literary invention. Merging the historical figure of Vlad the Impaler together with the fictional vampire doesn’t come without conflict. According to Duncan Light, in Romania, Vlad III is widely respected as a national hero who defended the country’s independence in medieval times. So especially during Romania’s communist times from 1047 to 1989, the Romanian tourism sector worked hard to distance itself from the vampire legend and to separate their national hero from Count Dracula. They designed tours focused purely on the historical figure and tried to sweep the vampire lore under the carpet. After the fall of communism, this strict separation gradually faded, although even today, Dracula tourism is more accepted than actively promoted.

Yet the fascination with Dracula persists. Visitors from around the world continue to travel to Romania in search of the vampire myth. There are numerous attractions and touristic sights that can be visited across Romania, especially in Transylvania. According to a dissertation by Tuomas Hovi, there are three different kinds of Dracula tourism. The first one is all about visiting places that have a connection to the historical figure of Vlad the III. A good example of this is Sighisoara, a city that is supposed to be Vlad III’s birth town and that is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Another approach to Dracula tourism is the kind that focusses on Bram Stokers’ novel. Tourists of that category might visit places such as Bistrița, the town where the book’s protagonist Jonathan Harker stays. Then there are places with little historical or literary connection at all but which have become iconic nonetheless. A perfect example of this is Bran Castle. The Castle is the first thing that comes up when looking up Dracula sights online, as it is being marketed as “Dracula’s Castle”. However, it has no proven link to either the vampire or the historical Vlad.

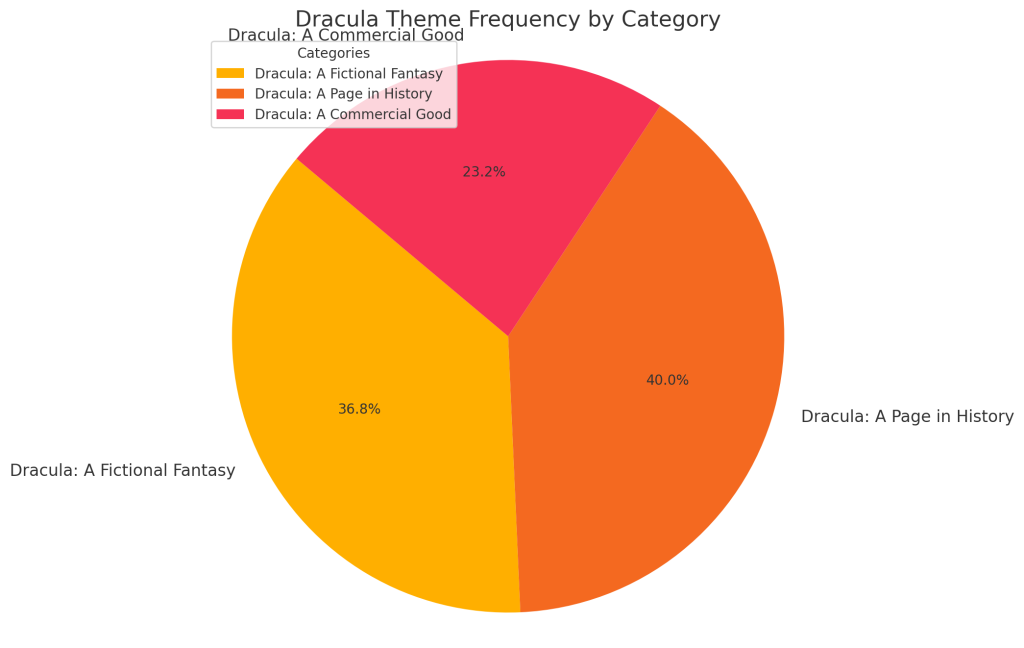

Of course, the presence of such a myth has an impact Romania’s identity. In conversations with locals, multiple people claim to believe in figures such as vampires or werewolves – or at least wouldn’t completely dismiss their existence. Research included in Maria Banyai’s Master thesis on Dracula Tourism shows what the word “Dracula” means to locals. She defined three categories in which Dracula can be perceived: A fictional character from literature, a part of Romania’s historical heritage, or as a commercial product for tourists. The results are visualized in the following graph:

The perception of vampire myths also varies across generations. According to Duncan Light, with the “Twilight” books and movies being really popular in Romania during the 2000s, the younger generation didn’t only fall in love with Edward Cullen but also found their fun in the Dracula myth and the relation to their country. The older generation still remains more skeptical and hostile towards Count Dracula and the tourists he brings to their country. Still, while Dracula doesn’t lurk around every corner in Romania, tourists who go looking for signs of the vampire will find them—whether in themed souvenirs, graffiti, postcards, or local legends. And of course, they can visit the famous sites—without any real risk of getting bitten.