Kamal van de Pol investigates the way the Welsh people are trying to reinvigorate their own language amidst the heavy English influence.

Cymraeg, or Welsh, whilst being the native language of the Welsh people, is considered a minority language. With a little less than a third of the population of over three million being able to speak the language, English is now the most widely spoken language and has been for many decades. However, the language seems to be going through a revival, on many fronts, from education to culture and promotion by many different groups.

The Welsh language itself is widely different to the English language, being from the Celtic family of languages. Which includes, the Irish language and Scottish Gaelic. This distance from the English language is one of the many reasons why the Welsh language is a big part of Welsh identity. Things such as a flag, cuisine, or shared history are important cornerstones to building an identity, but nothing is as powerful as a language.

In recent years the Welsh government has been working to promote the usage of the language and incentivize more people to learn Welsh from all ages, with the goal of reaching one million Welsh speakers by 2050. This strategy is called “Cymraeg 2050: A million Welsh speakers”. One of the main priorities of this strategy is the promotion of Welsh in the educational system. Welsh medium schools have been increasing significantly in number over the past few decades.

However, while many Welsh children grow up speaking the language during their primary school days, when they enter secondary school, many end up in English medium schools. Professor Colin Williams, from the School of Welsh at the University of Cardiff, observes and understands this change in school language. “A large proportion of parents send their children to Welsh medium primary schools, because they want them to have a founding in bilingualism.” But then some put them into regular English medium secondary schools as it may be a school closer to home and when the homework gets harder for the student, the parents are better able to help if it is in English if they don’t speak Welsh themselves. This effectively changes Welsh from being the children’s first language to their becoming second language. Professor Williams asks himself if Welsh will be relegated to being just a school subject, like Latin or Maths, instead of a language for life. Many children do still take up the Welsh language while in English medium secondary schools, with eight in every ten students taking a Welsh language course for their final exams. However, while still perhaps being bilingual, having Welsh primarily as a secondary language puts a bigger emphasis on the English language.

The Welsh government has recently outlined their strategy until 2026, with new areas of action to increase the usage of the Welsh language. These include amongst others the development of a strategy for the lifelong learning of Welsh, investing thirty million pounds to support local authorities’ efforts to expand their Welsh education and the piloting of a project which invites young Welsh speakers to teach Welsh to children after university. With these investments the Welsh government hopes to reach their 2050 goal of one million Welsh speakers.

The question remains if these sorts of measures are enough. It’s one thing to teach people to be able to speak a language, but to have them use it in their daily lives is a completely different matter. Because language and culture are spread by institutions the government cannot control, such as families, sports clubs, and local communities, the only tangible influence the government has is in the educational system.

Professor Williams has some remarks on the current focus by the government. “Producing the numbers isn’t the issue, the issue is strengthening the use of Welsh in real-life situations.” The aim of the government’s strategy is in essence to change the behaviour of society. “This is a most difficult task for the government to achieve by itself because the government doesn’t regulate most aspects of life.” Professor Williams does commend the strategy on capturing the zeitgeist of the times. “It’s ambitious and seems to have tapped into a more committed government approach to the survival of Welsh and its culture.”

For many people who have grown up in Wales, the constant, decade long tug of war between the Welsh and English languages has played a big part in their lives. Cultural historian and literary critic, Professor E. Wyn James grew up in the 1950s in the industrial valleys of south Wales and has witnessed many of the tensions. “If you told people they were English, well they’d be very upset. But many would regard themselves as British and as Welsh.” When he was growing up, the Welsh language had been in steep decline in his area. “There were individuals that would speak Welsh and certain contexts where Welsh would be used. But most people would never speak Welsh, and I don’t know how much they would even understand.” Professor James spoke Welsh and English at home until he went to school, but his parents were encouraged not to raise him bilingually for fear it would “confuse” him and affect his educational development. “Although there was some Welsh taught, after going to school I soon had lost most of my Welsh due to lack of use.”

There was also a certain attitude towards the Welsh language that both professors have experienced in their lives while growing up. Professor James notes that while he was growing up, there was a sort of acceptance that the Welsh language belonged to the past. “The language of progress was English.” At school as well, this divide between the Welsh language and English language was present, or as Professor Williams puts it, discrimination. “I went to the first experimental Welsh medium secondary school. There was a lot of discrimination towards Welsh speakers for being retrograde, traditional, non-modern, outdated and flogging a dead language.”

However, in current times the attitude towards Welsh has shifted dramatically according to Professor Williams. “Now you don’t get that, because most of the context is very positive and promotional.” He sees a much less discriminative tone now than before. “The problem with that, is that there’s less of a struggle or fight or reason to get involved, because you assume that the professionals have gotten it sown up.” He compares the language struggle of the past with today’s environmental struggle. “Anger, emotional strife, and calling out the poor practises. But that seems to have lessened a great deal now.”

One way this shift in attitude is palpable is in the ‘National Welsh College”. Professor Williams explains how about sixteen years ago the Welsh government invested heavily in Welsh lectures in non-traditional subjects. “Botany, Astrophysics, Pharmacy. Welsh used to be told in History, Literature, Theology and Geography.” But more professional subjects were not taught through Welsh. “Now this National Welsh College operates in every university in Wales.” A joint project between the government and universities even pays the salary for someone to teach a subject like Astrophysics in Welsh. “That increases the exposure to the language, and the demand for publications.” Thus, it is now possible for Welsh academic researchers to write papers in the medium of Welsh. “This expands the range of the Welsh language and it’s utility, in new subject matters.”

Professor James has also witnessed this change in attitude towards the Welsh language. “I remember someone coming to our house about ten years ago now. Working to fix the gas boiler.” When he heard Professor James and his wife speaking Welsh, his own passion flared. “He said: It’s not right, is it? Because Welsh is our language!” referring to the way the language had been downplayed, especially in education. He could not speak Welsh himself. “He came from a part of Wales where the language had not been a living community language for over a century.” Yet he still regarded Welsh as his language, a language he had lost. “You get that generally. When going back to visit my parents, when our children were small in the 1980s, the common response of the people in the village on, hearing us speak Welsh to our children was, Oh, it is so nice to hear the children speaking Welsh! I wish my parents had passed the language on to me.”

Many adults share this sentiment and want to learn Welsh themselves. The National Centre for Learning Welsh, which was established six years ago, coordinates the primary methods in which adults of any age, background and level can learn Welsh or learn it better. Hannah Thomas of the National Centre was brought up speaking Welsh but understands the reasons why adults who were not, choose to learn the language. “For children who go to Welsh medium schools, they are immersed in the language: they will start at age three or four and they will just pick it up, as it is easier for children to pick up languages.” When it comes to adults who are no longer in any educational system it is a completely different affair, where the National Centre has a big role to play. “There have been courses to teach adults ever since the 1960s, with different systems to teach Welsh. Before the Centre was established there were six regional centres. But the Welsh government decided it would be best to set up one National Centre.”

The National Centre as a central body works with eleven course providers throughout Wales, who teach the courses on behalf of the Centre. “But we have developed the curriculum, developed courses at five different learning levels.” These levels are taken from the European Framework of Languages. “If you are a complete beginner, you would start a course at entry level, and then it moves up to foundation, intermediate, advanced and proficiency.”

The National Centre’s courses are also customisable when it comes to frequency. As Thomas explains “A lot of courses can be two hours a week and it will take you several years to work your way through the levels.” But on the other hand, there are courses which are a lot more frequent, allowing people with more time to advance at a faster pace. This fluidity in timing is essential for courses catered to busy adults. “We’ve got people who have been learning with us for several years who are fluent, and then we got people who have been learning for two years who are fluent.” Of course, it is not all based on time, some people are better at picking up languages than others are. “If you already speak a number of languages, a new one is a lot easier.” In recent years the Centre has been providing free Welsh courses for refugees and asylum seekers. “And we’ve got one learner who is originally from the Ivory Coast in Africa. He literally learned Welsh within months, but he could already speak six or seven languages. So, he understood how languages are all about pattern.”

The courses of the National Centre are built for opportunities and choice. “Whether they want to learn at a fast or more leisurely pace, classes during the day or the evening, online self-study or tutor led.” This way people of all walks of life can learn the language at their own pace.

Apart from the normal courses, the National Centre also offers informal learning opportunities. “You can also go along to a conversation group or a quiz, or a book club, or a coffee morning, or a music gig.” These methods give people the chance to use their Welsh in a more daily life setting. “We want people to enjoy learning and speaking the language.”

A big question that arises is why: why do adults want to learn Welsh? The National Centre has done research on this and found that among many reasons the most common are: To support children who are in Welsh schools. To reconnect with their community, as Thomas explains “Lots of people do want to learn Welsh because they do feel it’s part of their identity.” Another reason is to widen their job choices. “In a lot of jobs, being able to speak Welsh is really helpful. For instance, certain parts of the health sector or care sector.” The National Centre also has tailored courses for sectors such as these, as relevant phrases and vocabulary can go a long way.

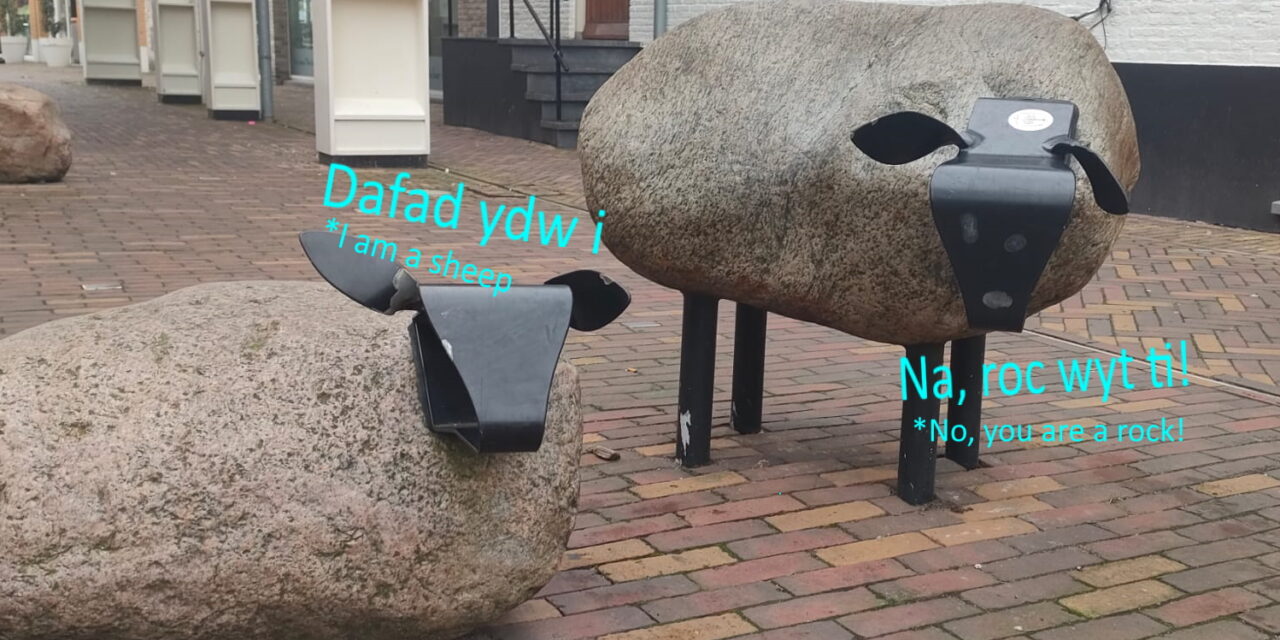

People come back into contact, or contact for the first time, with the Welsh language in many ways. “That’s why it is important that it is a visible language.” The National Centre has examples of learners who simply saw bilingual road signs, such as the ones used a lot in Wales, “and thought: Oh, what’s that about? I want to find out more.” Another common catalyst is the Welsh music scene according to Thomas. “A lot of people are interested in Welsh, because they love Welsh music.”

Ever since the pandemic hit, the courses the National Centre provide have been predominantly online. While for many learners this has proven troublesome, it has on the other hand brought in completely new learners Thomas and her colleagues would not have had otherwise. “People from outside of Wales can join a course really easily. So, we’ve got people from all over the world who join a class. People in Peru, loads of people in the United States, Australia, Dubai, Sweden, Canada. It’s fantastic that they’re all joining in. So, there is massive interest.” The National Centre plans to continue giving the option for online classes going forward. Even after the pandemic.

The Welsh language has had to overcome a multitude of hurdles. However, with the current enthusiasm surrounding the language and measures taken by many organisations, the future of Welsh appears bright. If one million speakers by 2050 will happen is still up in the air, but the language is anything but dead.